Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CablePaul Thomas Anderson’s character study baffled, aggravated & emotionally moved a divisive audience.

We say we want to see movies with people that look like us, with ordinary, unremarkable lives, but that’s not really true. Give us fantasy, give us beautiful people with lives that may be a little messy, but get better by the time the credits roll. Our time is short, why waste it on movies that illustrate how life is a long, often lonely series of fateful encounters and occurrences that, try as we might, we have no control over?

Magnolia, released twenty years ago this month, is arguably Paul Thomas Anderson’s most polarizing film. It has the audacity to be over three hours long, while not actually being about anything. There’s no real plot to speak of, not in the “point A to point B” sense, at least. There’s very little conflict (and when there is, it’s never really resolved), there’s no hero’s journey, and if the characters experience any sort of growth or change, it’s almost imperceptible, just enough to keep them going the next day. In the middle of the action (if you can even call it that), everyone stops to sing a melancholy song about how they’re foolish for thinking life is going to get any better. For some, Magnolia is a twee, melodramatic slog. For others, it offers comfort and hope, albeit served in tiny spoonfuls. Few major studio films have so accurately depicted the concept of bittersweet ordinariness — none of us are special, we’re at the mercy of what life decides to throw at us, and how we decide to handle it.

An ensemble piece, the closest thing the film has to a protagonist is Jim (John C. Reilly), a good-hearted man who’s unfortunately not all that great of a cop. Reilly has become so familiar for his comedic work that it’s hard to remember that his sad, expressive eyes–he was born to be a silent film actor–give his serious roles an exhausted, touching humanity. You believe in Jim, and his good intentions, and his embarrassment over losing his gun, and his awkward tenderness while courting Claudia (Melora Walters). We know right away that Claudia, with her drug addiction and traumatic childhood, might be too much for Jim to handle, but he wants to try, and the fact that anyone does is more than she’s experienced in a long time.

Far ahead of Jim in the sad sack-a-thon is Donnie (William H. Macy), a real life version of those memes about gifted children growing up to be miserable, neurotic adults. Donnie was bilked out of all the money he won as a kid on a TV quiz show by his parents, and now is just stumbling around in life alone, and, like Jim, stuck in a job he’s not very successful at. Donnie has laid all his hopes and dreams at the feet of Brad, a handsome bartender he’s besotted with, but who barely acknowledges his presence. He believes that the best way to get Brad to notice he exists is to get his teeth fixed, which he plans to do with money stolen from his ex-employer. There’s an interesting meta feel to this–Donnie clearly got the idea from a movie or TV show, and it doesn’t occur to him that such a thing isn’t as easy to get away with in real life. We see a movie character figure out that reality isn’t like the movies.

Few major studio films have so accurately depicted the concept of bittersweet ordinariness — none of us are special, we’re at the mercy of what life decides to throw at us, and how we decide to handle it.

The character connecting everyone, even if just indirectly, is Earl (Jason Robards), former producer of the children’s quiz show Donnie won, which is hosted by Jimmy Gator (Philip Baker Hall), Claudia’s estranged father. Earl is dying, and reckoning with a series of bad choices in his life, most predominantly abandoning his sick wife years earlier. Now all he has is a son who doesn’t speak to him, and a trophy wife, Linda (Julianne Moore), who has grown to love him, but is too caught up in her own shame and regret to tell him.

The only person who’s there to see Earl into his last days is Phil (Philip Seymour Hoffman), his nurse, and, along with Jim, the film’s moral compass. Considering how much of Hoffman’s career was devoted to playing troubled creeps and losers, it’s poignant to see him in such a role, with warmth and kindness all but emanating from his pores, particularly when you know that Anderson wrote the part with him in mind. We don’t really know much about Phil, but the fact that he offers comfort to Earl, and weeps at his impending death is what matters. Earl matters, to him at least, and, like Jim and Claudia, that’s enough.

Earl’s estranged son, Frank (Tom Cruise), is the closest thing the movie has to a villain. Frank is a motivational speaker/dating coach who says stuff like “Respect the cock, and tame the cunt,” while insecurity and sadness hangs in the air around him like bad cologne. He doesn’t seem like he really believes what he’s saying, and we see no evidence that his misogynist “dating advice” works for him. He’s just angry, and has found an easy, gullible audience in other angry men. If Magnolia was released now, he’d have a YouTube channel with a million subscribers.

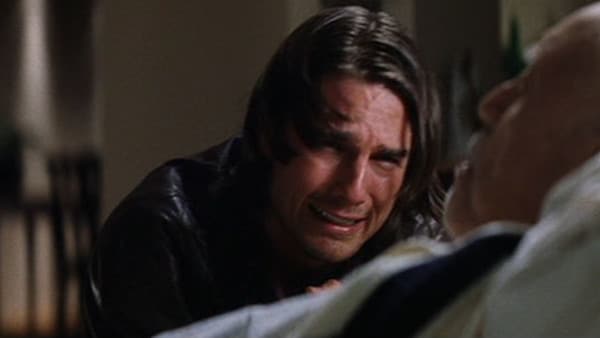

Magnolia is one of the few times in Cruise’s career where he’s been genuinely great, rather than just okay. Like when he portrayed a hammy 18th century vampire, he’s taking a real risk here, playing a character who seems to have no redeeming qualities, up until perhaps the last quarter of the film. Frank’s bedside reunion with Earl is fraught with rage and sorrow — he’s come back into his father’s life, only to face losing him again, for good. Largely improvised, it’s one of Cruise’s finest onscreen moments.

Despite their connections, and the fact that they’re all within a mile of the same place, many of these characters don’t ever encounter each other. They’re all tiny ripples in each other’s ponds, becoming indirectly associated by chance. There’s a saying about how we’re all walk-on characters in the movies of other people’s lives, and that’s what Magnolia is, a series of short films that all have a thread tying them together. Sometimes the thread is so thin you can barely see it, but it’s there.

Many of the characters, without ever realizing it, have something in common — Claudia and Linda are both addicts, Frank and Claudia both refuse to use their father’s last names, Earl and Jimmy both have cancer, Jimmy and Donnie are both alcoholics. There’s even two quiz kids: Donnie, and Stanley (Jeremy Blackman), both of whom only matter to their parents when they’re winning money. The fact that Stanley’s father, near the end of the film, icily ignores Stanley’s suggestion that he needs to “be nicer” to him is sobering proof that the cycle always continues, for good or ill. Maybe Stanley will grow up to be just like Donnie, or maybe something he’ll never see coming will turn him down a different path.

While focusing so much on the bleaker aspects of it, it’s hard to remember that Magnolia is genuinely funny at times. Not fall down funny, but in that sort of bemusing way, like when you have an encounter with an eccentric stranger. Donnie has a strange, elliptical conversation with a fellow bar patron who calls himself Thurston Howell (Henry Gibson). During their sweetly clumsy first date, Jim abruptly blurts out his embarrassment and insecurity about his job, and Claudia is so impressed with his honesty that she kisses him. Jim seems a little surprised and puzzled by this. After all, he doesn’t know any other way to be.

If Magnolia doesn’t have a happy ending, per se, it at least has a hopeful one. Because like I said above, with hope there’s a reason to keep going. Every day we wake up and choose to keep moving ahead is another day for things to turn around and go our way. And if not, then maybe the next day, or the one after that. We won’t know unless we keep going.

Earl’s pain comes to an end, and though it’s a fraught reunion, he gets to see his son one more time. Jim’s missing gun reappears, having seemingly fallen out of the sky. When Linda awakens from a suicide attempt, she’ll find a most unlikely person sitting at her bedside: Frank, taking the first steps towards letting go of years of hurt and anger. We close on Claudia (appropriately, as she was the first character Anderson created, spinning everything off of her), sure she’s pushed kind, tenderhearted Jim away with all the broken, jagged parts of her. But he’s there, and he’s asking for a chance to be with her, to be the strength and steadfastness that she needs. Claudia, her teary, tired eyes telling the truth, that this life, it’s so damn hard, and so long, looks at Jim as he makes his speech. Then she look at us, and smiles. A little bit.