One of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s finest moments has him playing a beacon of comfort and compassion.

Phil Parma (Philip Seymour Hoffman) isn’t headed home yet. He’s been working all day, an emotionally exhausting twelve hours spent caring for his patient, Earl Partridge (Jason Robards). Earl’s bedridden and in constant pain – as his doctor bluntly tells his wife (Julianne Moore), “He’s not going to make it.” Phil’s job is to help as much as he can.

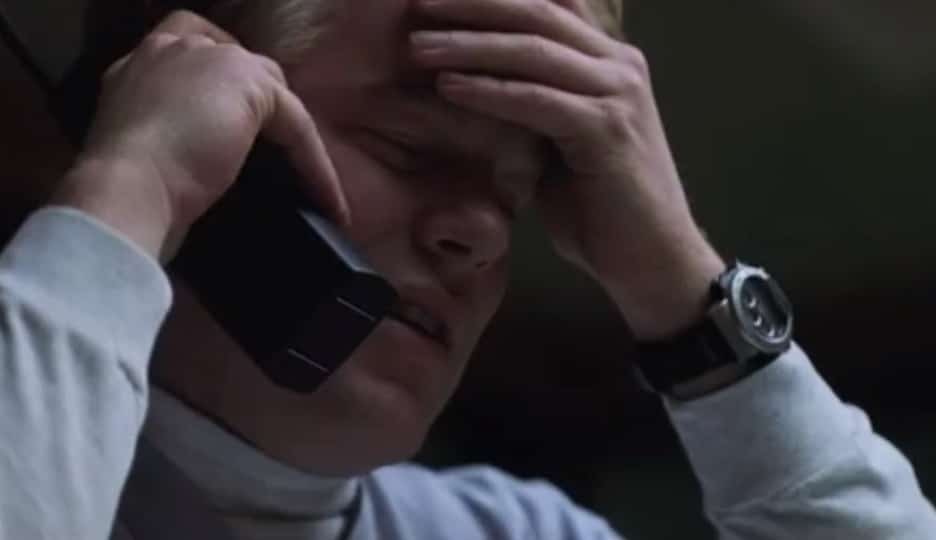

When the nurse who works the next shift arrives, Phil opens the door to a gross, rainy night. He sends his co-worker away with a hushed “Yeah, I think I’m gonna stay on, stick it out.” His voice is quiet, and at a glance, his mannerisms are nonchalant. But just as Scotty J. choked back tears in front of his cherry red sports car, Phil’s barely holding it together. Still, in the moment he could go home, the moment he probably should go home, he stays to care for a dying man.

Magnolia intimidates. With his third feature, Paul Thomas Anderson traded in the virtuosity of Boogie Nights’ elaborate tracking shots for an absolute excess of characters, as we follow nearly a dozen people going about their day in the San Fernando Valley across a 188-minute runtime. Their stories are intertwined by shared circumstance and coincidence rather than an intricate plot. Most everyone grapples with the mistreatment they’re responsible for, or the mistreatment they’ve received. Parents hurt their kids, kids who grew into a version of their parent – Anderson understands that these ills aren’t isolated incidents, they happen in cycles. “Life ain’t short, it’s long,” Earl tells his nurse. “Phil, help me. What did I do?”

In this desolate reality, only two people have a degree of distance from the suffering that surrounds. They are men defined by their professions – it’s their job to help. The first is a dumb, well-meaning cop named Jim Kurring (another early Anderson regular, John C. Reilly). The framing of this L.A.P.D. officer is Magnolia’s sole blemish: it’s very difficult to believe any cop is a force for good, much less one who we meet yelling and pulling a gun on a woman of color. Anderson’s conception of Kurring and Reilly’s performance produce a complex portrait of a policeman – working out to what extent he’s purposefully “problematic” and how this compares to copaganda as a whole would take its own essay, and you aren’t reading J.C.R. I Love You.

All this to say, whether he meant to or not, Anderson cast Hoffman as the only true light in Magnolia’s dark, dark tunnel. He’s not repressed, villainous, or tortured, he’s not angry, rude or silly, he’s just a guy trying to help. Hoffman was barely in his thirties when he played this part, and he comes across as both experienced enough to do his job well, while still holding on to a certain youthful energy for the work he does. He’s attended to folks in Earl’s position before, but maybe after another five years in hospice care he wouldn’t stay on for an extra night shift.

Phil and Earl have an almost playful rapport the first time we see them interact, but it’s always clear that Phil takes his job very seriously. When Earl demands to get in contact his estranged son, Phil doesn’t question him, he jumps into the arduous task. The nurse goes above and beyond what he’s being paid to do – we watch as he crosses the lines of his job description to help the old man. And help him what? How much should old men who have done terrible things suffer on death’s doorstep? Or, as Kurring ponders at the end, “What can we forgive?”

I don’t know. I don’t think Magnolia or Paul Thomas Anderson know either. But so much is broken. The world needs repair. Phil’s so present, so patient, and so giving to Earl, Earl’s wife Linda, and his son Frank (Tom Cruise). He feels some of their turmoil and struggle – who wouldn’t? – but he doesn’t break down entirely. When Linda explodes at him for inviting Frank and slaps him across the face, Phil stays calm, and then accepts her apology. When Frank issues a childish list of demands upon entering his father’s home, Phil calmly reassures him. Because of his nurse, Earl sees his son again before he dies.

Something ineffable in Hoffman’s mannerisms, in the way he listens, expresses more than just patience but warmth. There’s a thin line between the two. With this collaboration, Anderson handed Hoffman a deceptively simple part: instead of displaying a cascade of opposing emotions as he did in Boogie Nights, playing “Phil,” meant striking a single, positive note and maintaining it. As late on-screen text reads, “But it did happen.” Phil stays for the night shift in an attempt to heal that which cannot be healed. What more can any of us do?