Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableNight Shift, Ron Howard’s Michael Keaton-star-making mortuary-set sex comedy, is unlike anything he’s made in quite some time.

Ron Howard has been directing feature films for almost 45 years now (his latest, Thirteen Lives, has just opened) and I think most would agree that he long ago proved himself behind the camera—he works well with actors, tells his stories cleanly and efficiently and, barring outliers like How the Grinch Stole Christmas or Hillbilly Elegy, even his films that don’t quite work never go completely off the rails into complete disasterdom. If there is a flaw to Howard’s method, it is that there is never a personal touch or sensibility to most of his films—even the most ardent auteurist would struggle to find any sort of artistic throughline connecting his work. Sure, there is something to be said for solid, sensible craftsmanship, but Howard as a filmmaker could stand to let his artistic freak flag fly once in a while.

Howard did do this once early on in his career when he was still trying to establish himself as a director and aiming to break away from his goody-goody sitcom persona. It resulted in what may be my personal favorite of his films to date, the 1982 comedy Night Shift. Yes, the film’s premise has not exactly aged well in the 40 years since it premiered—it was frankly a bit dubious even back then—but it more than makes up for it with the sheer wildness of that premise, ragged energy that fits the tenor of the material and, perhaps most importantly, one of the most sensational big-screen debut performances of the era.

Henry Winkler, Howard’s longtime Happy Days co-star, stars as Chuck Lumley, an exceedingly mild-mannered financial wizard who left the high-pressured world of Wall Street and now works as an attendant at the New York City morgue. Alas, Chuck is so introverted that he is unable to stand up for himself to anyone, be it his neurotic fiancee, the deli that screws up his order, or the boss who informs him that he is being “promoted” to working the night shift and will also be training a new co-worker.

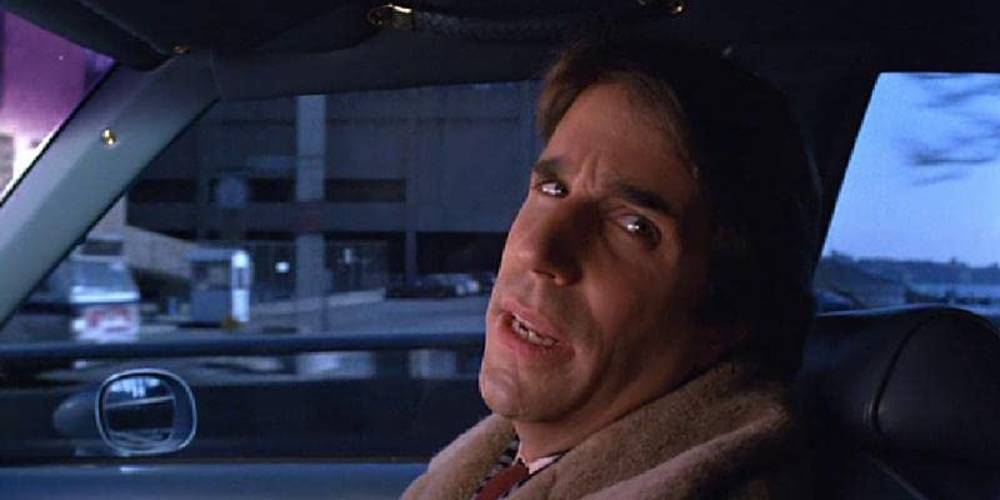

All this leads up to Night Shift’s key scene, one that hit viewers the same way Eddie Murphy taking over the redneck bar in 48 Hrs. did—the arrival of that new co-worker, a fast-talking self-described “idea man” named Bill Blazejowski who bops on in to the beat of his Walkman and lays out an astonishing array of patter, occasionally interrupting himself to capture one of his brilliant money-making schemes on the tape recorder he always carries with him. Bill is played by Michael Keaton, who up to this point had starred in a couple of short-lived sitcoms and done some bit parts in a handful of movies. From the moment that he appears, it is clear that a star was born.

One night, Chuck lends assistance to Belinda (a pre-Cheers Shelly Long), a prostitute who lives in his building working on her own following the murder of her pimp at the hands of some gangsters. When he mentions this to Bill at work, later on, Bill has an especially outrageous idea—they could serve as the pimps (or “love brokers,” per Bill’s rebranding) for Belinda and her colleagues and make the morgue their base of operations. Chuck is appalled at first but, having already begun to develop feelings for Belinda, agrees to do it. The combination of Bill’s entrepreneurial spirit, Belinda’s crew of willing hookers and Chuck’s financial acumen (even offering advice to the women, from whom he and Bill collect only 10% of earnings, on how to invest their profits) makes their venture a success, leading to the inevitable complications involving the police, the mob and Chuck’s relationship with Belinda before—what else? —a happy ending for all involved.

Okay, the basic premise of the film is a bit problematic, as the kids say. It should be noted that back in the early 80s, not only did it not raise that many eyebrows (minus wags that such a film was coming from the guy who used to play Opie), it was one of a string of films in which slightly nerdy white guys garnered self-respect and fattened their wallets by taking unexpected detours into the business end of the flesh trade—including the Dan Aykroyd solo misfire Doctor Detroit (1983) and a little coming-of-age film entitled Risky Business (also 1983). What can I say—things were weird back then.

With its combination of sly social satire (at least until the closing minutes), genuine eroticism, and a star-making turn from Tom Cruise, Risky Business was by far the most successful of the bunch, but Night Shift equals it in several ways. Apparently inspired by a real-life story involving a prostitution ring run out of a morgue, Happy Days writers Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel’s screenplay took a story that could have been grim and sleazy in the wrong hands and spun it in a more overtly farcical direction that, in concert with snappy dialogue, oddball characters and loopy situations makes it feel like, and I mean this in the nicest sense of the word, a well-oiled and long-running sitcom at its peak.

Unlike most of his subsequent features, Howard is not exactly striving for respectability here and Night Shift is all the better for it. There is a welcome looseness and spontaneity to it, and he deftly shapes the offbeat and potentially offensive material in ways that maximize the laughs and make the more sincere moments palatable. The biggest connection between this film and Howard’s future work is his deft handling of the actors. Keaton is the obvious standout in the cast, of course, but taking a cue from how John Landis deployed the similarly scene-stealing John Belushi in National Lampoon’s Animal House, Howard wisely refrained from overusing him and wearing out his welcome.

While Keaton’s the scene stealer, Winkler acquits himself well and scores a lot of laughs in his struggle to remain unflappable in the wake of Hurricane Blazejowski. The only casting that doesn’t quite hold up today is Shelly Long, though this is not entirely her fault—she is perfectly fine as Belinda (although one wishes that the Second City veteran might have gotten a few more opportunities here to be funny) but once she achieved stardom on Cheers (which premiered a couple of months after Nigh Shift), her persona from that show of an uptight intellectual became so prevalent that going back to see her playing a prostitute cannot help but seem a bit strange. (Other soon-to-be-familiar faces making early appearances here are Kevin Costner—a frat guy in a wild party at the morgue—and Shannen Doherty—an ersatz Girl Scout who leads her pack to beat up on Chuck at one point.)

When Night Shift hit theaters in the summer of 1982, it was a modest success at best—like most other films that season, it was hit by the juggernaut that was E.T.—and most people would catch up with it later on—it frequently turned up on HBO. For both Keaton and Howard, though, the impact would be more immediate. Even those who didn’t care for the picture praised Keaton. He followed Night Shift with the title role in Mr. Mom (1983) and a career that continues to run strong today.

As for Howard, he followed Night Shift with Splash (1984), Disney’s first attempt to try something a little more adult, and its success helped cement his dream of becoming a filmmaker. Since then, Howard has made a host of blockbusters and won numerous awards for his direction. He has even branched out into documentary work in recent years. But Night Shift, for all of its silliness, still stands in my mind as the most cheerfully entertaining of his films. I still hope that one day he will try something along its lines again.