Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableNic Cage sinks his teeth into Count Dracula’s camp menace, but the movie around him is a limp action-comedy that doesn’t know what it wants to be.

There’s always been something of the vampiric in the acting style of Nicolas Cage; his dark, intense eyes, his hunched gaze, his predilection for sinking his teeth into the scenery as vociferously as he might an unsuspecting jugular. And yet, it’s wild to think he’s never played a gen-you-wine bloodsucker before now. Sure, there’s Vampire’s Kiss, the great 1988 dark comedy in which he played a manic ’80s business guy who imagines himself to be one — but those were more the panicked neuroses of your typical self-destructive Cage protagonist. But in Chris McKay‘s action-horror-comedy Renfield, he’s the real pale deal: Count Dracula himself, complete with velvet capes, a mouth full of fangs, and an unquenchable thirst for hemoglobin.

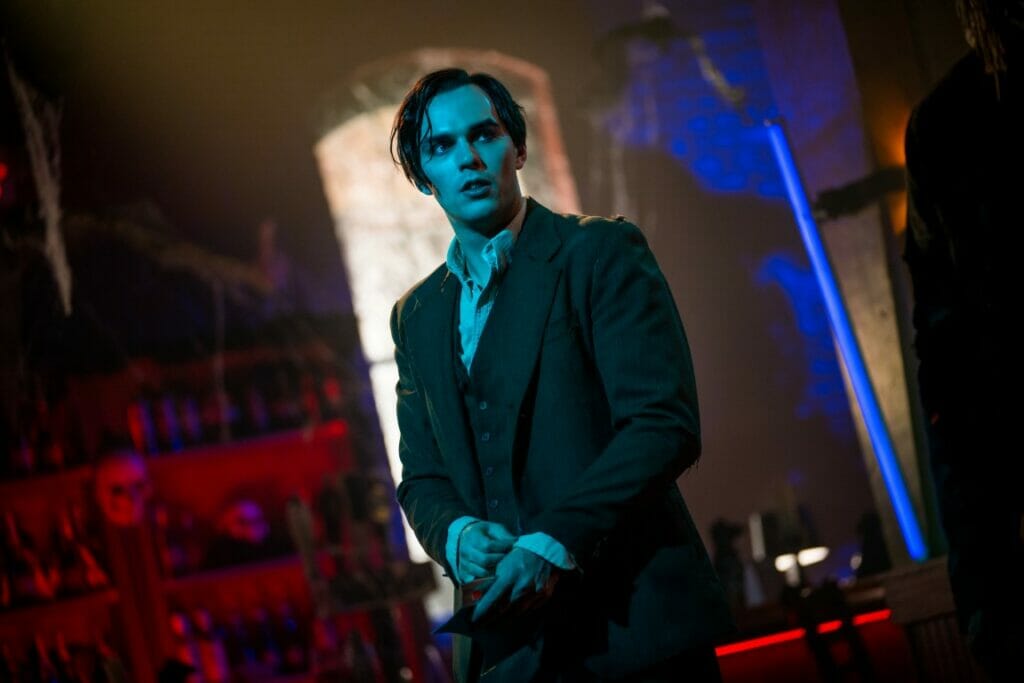

Trouble is, Renfield ain’t the kind of movie that makes use of such pitch-perfect casting. In fact, Cage’s Dracula seems like mere window-dressing on which to hang a frustratingly thin punch-em-up in the glib mode of Kick-Ass, which is a real pity. As the title implies, we don’t follow Cage’s Drac, but rather his iconic familiar Renfield (played with sheepish charm by Nicholas Hoult), a stammering pushover who’s been doing Dracula’s dirty laundry for nearly a century now. (The film is most charming in its opening minutes when their history is depicted through delightful stylistic homages to Tod Browning’s 1931 classic Dracula, as well as the Christopher Lee Hammer horrors of the ’60s and ’70s.)

But the decades of manipulation and servitude have gotten to him, which leads him to that most 21st-century of phenomena: a support group for people trapped in toxic relationships.

If Renfield had committed to this premise, a deep dive into Renfield’s codependency with his demonic master as told to a group of average Joes who can arm him with the power of positive affirmation, it’d be a dark horror delight. But alas, McKay (and screenwriter Ryan Ridley) have seemingly been bitten by a radioactive Mark Millar; in the interest of turning this into a broad four-quadrant crowdpleaser, they’ve grafted this premise atop a hard-R action comedy that fits about as well as Renfield’s baggy, turn-of-the-century suit.

You see, one of the film’s many contradictory rules demands that familiars gain superhuman powers when they chomp on a bug — when Hoult chomps on a spider or a fly, he becomes a John Wick-like badass, flipping over baddies, squashing their heads like cantaloupe and using their dismembered arms like javelins. Sure, there’s a kind of outre delight in how much fake blood and viscera these action scenes spill, but it’s all chopped to bits in the editing bay, so who Renfield is tearing apart and who’s shooting at who gets a bit lost.

In the interests of giving Renfield as many bodies to stack as possible, Hoult’s journey to self-actualization is interrupted by a do-gooder cop (Awkwafina, sorely miscast and underwritten) who eventually ropes him into her quest to take down a nondescript crime family in New Orleans, where Renfield and Dracula have set up shop while the latter rebuilds himself after his latest near-miss by the Catholic Church. These scenes ostensibly drive the film’s primary action, and yet every time we see Ben Schwartz or Shohreh Aghdashloo preening on screen as the mother-son duo who runs the gang, the whole thing just grinds to a halt. They feel like necessary evils, glommed onto the script after execs got spooked that a whole film just about likening the monster-familiar relationship to domestic abuse would be too boring for Moviegoer Joe.

This is a shame because it leaves Renfield a film nervously darting between what it really wants and what its audience demands of it — sound, well, familiar? Hoult and Cage have delicious chemistry, Hoult yammering with Hugh Grantian charm through the thinnest of personal journeys, while Cage seethes through pale makeup and his big bug eyes.

Both are giving their best, but are hampered by both script and production: Renfield’s cowardice is complicated by his action-hero bona fides, and Cage’s prosthetic chompers muffle half his dialogue. You can tell he’s relishing the words that spill from his mouth, but Heaven help you if you can understand them. Still, his physicality, the glee with which he sips blood from a martini glass garnished with eyeballs or overpowers Renfield’s timid attempts at rebellion with a single phrase, is enough to leave you wishing he was the actual crux upon which the movie rested.

As critics, it’s important for us to review the film that was presented to us, rather than lament the film we wish we got. And yet, with Renfield, the seams are so blatant that it’s hard not to see a version of this that works much better. Ditch the gang members, chuck Awkwafina and the hastily-edited fight scenes, and just turn it into an arch retrospective on one of horror’s most iconic dynamics, framed through the clinical, therapeutic language of our postmodern age. Just imagine Renfield telling Count Dracula, “I’ve treasured our season of friendship, but we’re moving in different directions in life.” Tell me that wouldn’t be more entertaining than another yawn-inducing gunfight in a neon-drenched mob manor.

Renfield mumbles affirmations as it stumbles into theaters April 14th.