Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableAlan Parker’s psychedelic edifice to the music of Pink Floyd is just as gripping and relevant as it was four decades ago.

Pink Floyd: The Wall, Alan Parker’s bombastic screen version of the classic 1979 Pink Floyd album of the same name, made its debut at an out-of-competition gala screening during the 1982 Cannes Film Festival at a volume so loud that the paint was reportedly peeling off of the walls. As the story goes, once the film came to its conclusion and the presumably dazed audience launched into the obligatory post-screening ovation, Steven Spielberg, who was at the festival presenting the premiere showing of E.T., turned to his seatmate, Warner Brothers head Terry Semel, and supposedly remarked: “What the fuck was that?”

This sentiment that pretty much everyone who has experienced this film has asked at some point. It is, if nothing else, a singular experience—a one-of-a-kind riot of sound, fury, and spectacle whose production would be deemed a miserable experience by practically everyone who worked on it even as it became an instant and lasting cult classic.

The Wall was not the first time someone attempted to adapt a concept album to the big screen. The Who had seen their rock operas Tommy and Quadrophenia turned into films, and there was also the infamous Bee Gees/Peter Frampton-led visualization of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. When Roger Waters presented the concept, he planned to unveil it to audiences first as an album, followed by an elaborate concert presentation (presented in merely four cities throughout the world). They would also craft a movie that would incorporate footage of the shows, with animations from Gerald Scarfe and extra scenes featuring Waters in the central role of zonked-out rocker Pink. It would be directed by first-time filmmaker Michael Seresin under the supervision of Parker, who turned down the job of directing but chose to serve as a producer.

Those plans quickly fell through. The concert footage shot specifically for the film meant to make up a large percentage of the final product was deemed unusable for technical reasons. Parker felt mixing such material with the animation and the scripted scenes would prove too jarring. Scarfe and Waters (who also penned the screenplay) agreed with Parker, leading to Seresin leaving the project and Parker officially taking over as director.

Between the decision to scrap the live footage and a reportedly underwhelming screen test, the notion of having Waters star also fell by the wayside. He would be replaced by Bob Geldof, who had never acted before but who was known as the leader of the Boomtown Rats, one of the many punk groups that sprang up in the late Seventies to rebel against the bloated excesses of top rock groups like…uh, Pink Floyd. (The story goes that while taking a cab ride during the negotiating process, Geldof expressed his deep misgivings about the project to his manager, not realizing that the driver was Waters’s brother.)

By all accounts, the film’s production was a nightmare as the three key creative personnel clashed with each other over who was in charge. Already a highly regarded filmmaker, Parker naturally felt he should be in charge. Meanwhile, Waters, who was used to getting his way in the recording studio, felt that he should be in control of the profoundly personal source material. (The ensuing strife is recounted in Scarfe’s The Making of Pink Floyd: The Wall, his 2010 book chronicling the entire history of the work from the album’s development to the stage version Waters would tour around the world in 2010-11.)

The one thing they all seemed to agree on was their praise for Geldof’s performance, a work so committed that when he badly slashed his hand during the big hotel trashing sequence, he insisted on completing the scene before getting it treated. (That moment is in the final film.)

What emerged from all of this strife was a film that was unlike anything that had been seen at the time and still has the power to shock and baffle 40 years later. While a riot between young rock fans and cops breaks out in the streets outside the faceless arena where he is set to perform, alienated rock star Pink (Geldof) sits vacantly in his hotel room, flashing back on the failures and traumas of his life. There’s the loss of his father in WWII, an overbearing mother, the oppressiveness of the British school system, the collapse of his marriage, and his overindulgence in booze, drugs, and anonymous sex with groupies. All the while, he builds a metaphorical wall in his mind to isolate himself from the world.

Most viewers will either love or hate it. But it’s unlikely they’ll ever forget what they saw.

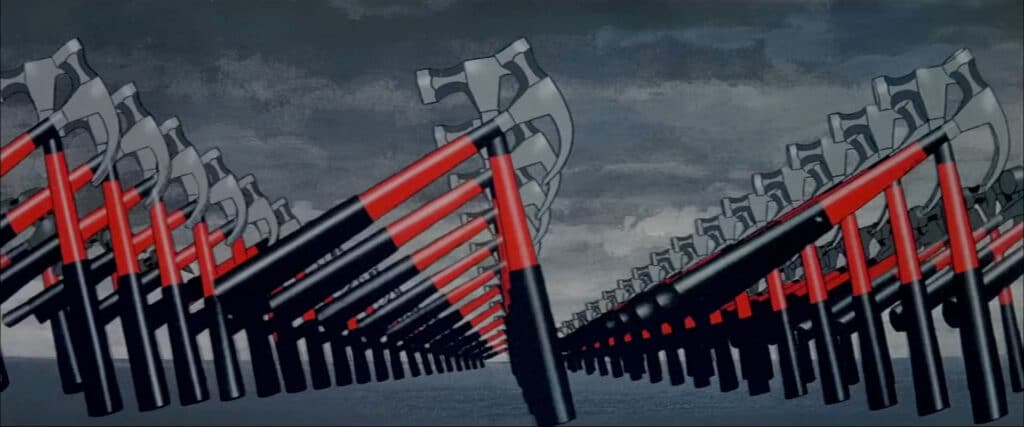

He drifts entirely into madness for a bit, imagining himself a genuine fascist leader and his audience little more than mindless foot soldiers to do his bidding. Eventually, he steps away and puts himself on trial for his sins, with his sanity in the balance.

However, what sets The Wall apart is not the story as much as the way that story is conveyed. Although it contains nearly all of the songs from the original album and a couple of newly written songs from Waters, it’s neither a musical in the traditional sense nor a concert film. It’s essentially a 95-minute-long music video, featuring Geldof and his costars (including Bob Hoskins in an early role) making their way through scenes and images inspired by the songs on the album. These range from the ordinary (trying to wake Pink up for a show after ODing) to the hallucinatory.

As Pink’s grasp on reality deteriorates, so does the film’s, resulting in terrifying imagery, including Pink shaving off his body hair (and much more) and animated flowers that resemble a Georgia O’Keefe nightmare come to life. All this is set to the tune of the Pink Floyd music, which starts like a sonic blast and never relents its concussive force until the end credits roll.

The result is one of the most unremittingly grim films of any type ever produced—the painful and unsparing tone established at the start never changes, and there is nary a laugh nor a moment of lightness to be had. The imagery is dark, grisly, and unsparing, and the music is equally unrelenting. Plus, it asks audiences to focus their energy on a protagonist so profoundly alienated that he hardly says a single word. Anyone expecting a conventional musical would be appalled by the surreal imagery. Those who aren’t already fans of Pink Floyd would run for the aisles after a few minutes of sonic bludgeoning.

While The Wall is undeniably one of the most depressing movies ever made, it’s also uncommonly compelling. Waters may have clashed with Parker over the direction of the film. Still, he was lucky to have gotten the project into the hands of a serious filmmaker who could provide the wild imagery and psychological subtext required to sympathize with Pink and his existential ennui. Likewise, Parker lucked out that Waters provided him with a song cycle that felt like a genuine dramatic narrative, not just a bunch of haphazardly stuck-together tracks. Scarfe’s animations are spectacular, and Geldof’s surprising performance suggests that he could have become an exciting actor if he had decided to give up his day job.

The film also contains some of rock music’s most startling and memorable images. The most famous, of course, is the visualization of “Another Brick in the Wall II,” in which Waters’ alienation from the British school system takes the form of kids stifled by strict, brutal taskmaster teachers before literally being tossed into a meat grinder. Pink picks up a groupie (Jenny Wright) and takes her back to his room before trashing the whole thing in a trance so profound he barely registers her presence. He fully imagines himself as a fascist leader, strutting on stage and exulting in his power over the masses.

Upon its release, The Wall would become a decent-sized hit at the box office and a perennial best-seller on home video over the years. However, the production would take its toll on all involved and would also prove to be one of the final straws on the camel’s back that was the Waters iteration of Pink Floyd. Following the contentious recording of The Final Cut, a 1983 album originally meant to be a collection of the new music composed for the film, Waters would leave the group, kicking off years of legal skirmishes.

But the film endures, and hasn’t lost any of its power through the generations. The psychological trauma and alienation issues it discusses are just as prevalent today as in 1982. The imagery on display is so primal and striking that it doesn’t feel dated in the slighted. Yes, Pink Floyd: The Wall may be a long way from the likes of A Hard Day’s Night, and it’ll be too much for many audiences to take. Most viewers will either love or hate it. But it’s unlikely they’ll ever forget what they saw.