Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableProduction I.G’s film fumbles whenever it has to address something else besides its epic attributes.

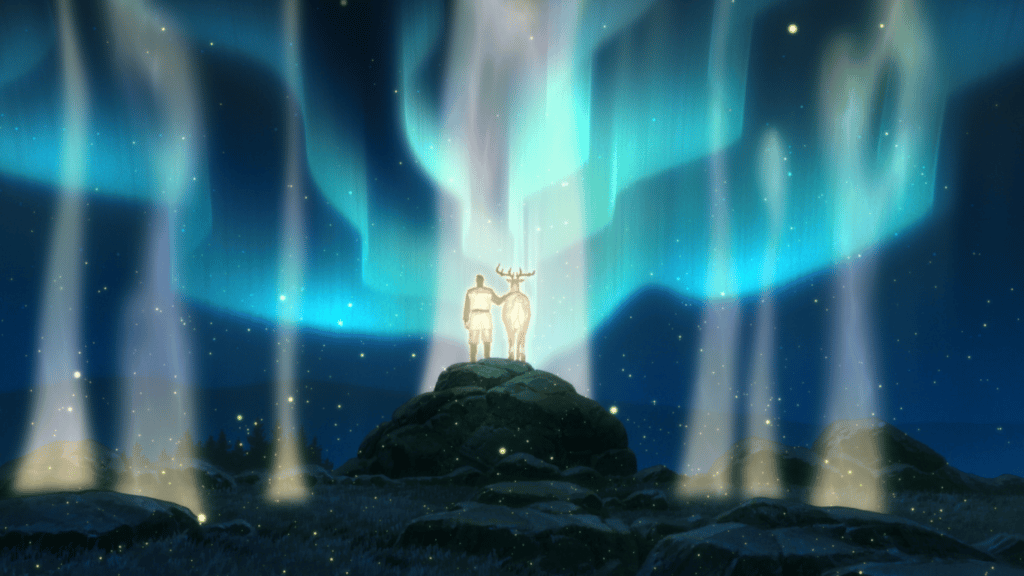

From the start, GKIDS’ latest acquisition, The Deer King, can call itself the spiritual sequel to Princess Mononoke without fear. Like Studio Ghibli’s 1997 title, the adaptation of Nahoko Uehasi’s eponymous novel series also has world-building text about clashing factions and ancient magic unfolding over vivid forests and stirring music. One of this film’s directors, Masashi Ando, was a supervising animator for the other one. Wolves and elks are again the beasts with the most screen time.

This illusion only works for a short while, however. The wolves aren’t white, and they’re also the heart of a lethal plague known as “Black Wolf Fever” (known in-universe as “mittsual”). Whereas Mononoke uses writhing worms to signify affliction, The Deer King opts for seemingly sentient purple plasma. The opening text runs and lingers for longer than expected, almost as if it’s compensating for excised footage meant to introduce the setting of Aquafa and their imperial rulers, the Empire of Zol. That also might have been the earliest sighting of the film’s main flaw: covering a lot of ground with methods that are not the most ideal.

As much as The Deer King is a story about power, it also chronicles ideology and humanity. Amid the (semi-cold) war between the upper echelons of red-dotted Aquafaese and blue-coated Zolians, and between them and the hostile nature, there is also the search of a doctor for a mittsual cure plus the trials of two greatly destined survivors. While writer Taku Kishimoto is aware they’re all connected, his approach to having them coalesce is at best sporadic and at worst flat.

In their campaign to reclaim the land from the Aquafa King (Tesshō Genda) and his right-hand man Tohlim (Yoshito Yasuhara), which might not be as physical as swords-and-armies-driven as thought, stakes are scarce when they shouldn’t be. While it’s precisely the sort of bureaucratic action that affects folks high and low, it only has an impact when called upon and is not the result of built-up pressure.

There’s also a diminishing effect in whatever earth-shattering findings that the lauded Dr. Hohsalle (Ryōma Takeuchi) and his burly guard Makokan (Tooru Sakurai) come across. Although the duo is on a path to reshaping the perception of the land’s denizens, absorbing their knowledge is hard. When their discoveries have been shown, they will be commented on—extensively.

In fact, no element in the film lacks some extensive context. But back to the duo: In all the time they’ll spend talking, they supply enough evidence to conclude that Dr. Hohsalle is a bishōnen (or ikemen?) dream came true and that Makokan is emblematic of the comic brute trope Japanese animation might need to retire.

How can love be any different when its politics and ideals are so featherweight? Despite The Deer King’s inroad being the relationship of two unlikely souls, the prisoner scarred by the past Van (Shinichi Tsutsumi) and jolly orphan Yuna (Hisui Kimura), not much of it receives emphasis. But there are plenty of conveniences when they show their bond, making their ties to the mittsual’s rage and the nation’s struggle perfunctory. The two being specks in designs much bigger than them should have been home to rousing dramatics, yet what we have now is just, well, them being underdeveloped.

Regarding scope, The Deer King can awe. Ando and his co-director, Masayuki Miyaji, whose credits include storyboarding Attack on Titan episodes and 2018’s Pokémon the Movie, have the know-how to depict strength regardless of source. The piercing ability of a precision arrow as it left the bow. The world’s vastness is colored with robust hues, cultures (traces of ancient China, Mongolia, and Tibet are seen), and exclusive nouns.

The notion of mortality is exemplified through the prevalence of death, Van’s nightmares, and, unsurprisingly, the banquet of set pieces. One of the latter has a couple of characters under attack from stilt-walking warriors in foggy and muted woods, and it’s imbued with more tension than skirmishes the film would deem key. It’s also a reminder that the film could have benefited from more personal, intimate brushes.

The Deer King (Shika no Ō) is now playing in theaters in dubbed and subbed versions.