Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableDanielle Lessovitz’s debut fails to probe its themes, marginalizing the community it aims to highlight in the process.

It doesn’t take more than a minute or two for Port Authority to start dangling its main theme right in front of the audience. On probation and having just gotten off the bus in New York City, Paul (Fionn Whitehead) roams the station, showing strangers a picture and asking if they’ve seen a woman. But you see, it’s not like she’s missing. He’s the one who’s missing, the woman in the picture being his sister, Sara (Louisa Krause), who’s refused to pick him up and take him in. He has no family. The movie really wants to make sure you get it. What makes it hard to buy is how inorganic Danielle Lessovitz’s feature debut is.

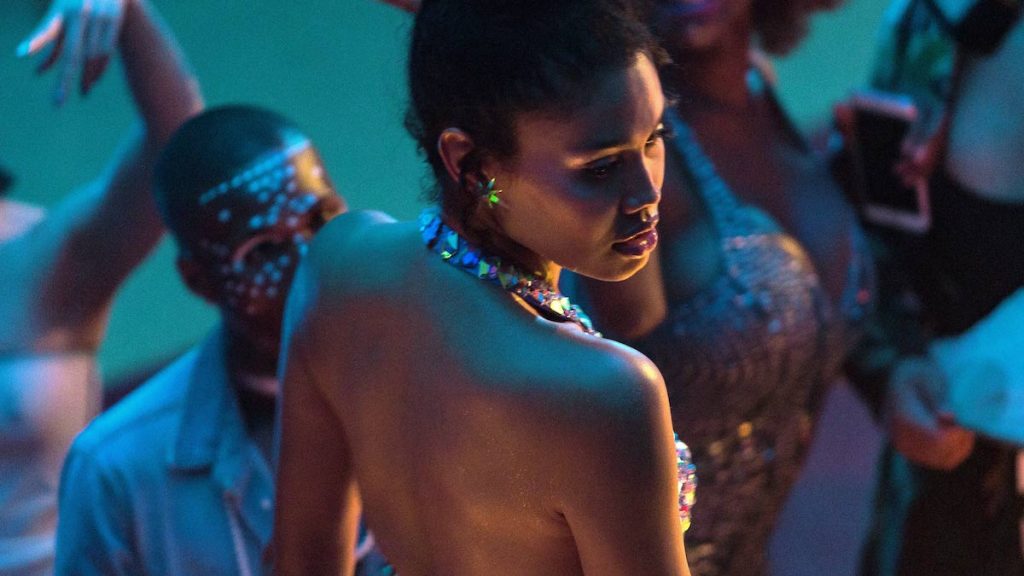

For Paul, a main shift in his life comes immediately afterward. For the movie, its issues come to a head as soon as it introduces the world it attempts to shine a light on. It’s outside the port authority that someone catches Paul’s eye. It’s Wye (Leyna Bloom), a young woman voguing with her own makeshift family. They exchange nothing more than a glance. Paul scopes her. He even follows her for a bit. They have a conversation, she invites him to a ballroom rehearsal of hers, and the two dip their toes into what might be a romance.

The wrinkle between them? He’s white and cisgender while she’s Black and trans, the latter he only finds out later. The wrinkle for the movie? Lessovitz’s script isn’t about Wye, the trans experience, or how she’s found a home with other LGBTQ people of color. These identities are near interchangeable here. In the context of the story as Port Authority approaches it, Wye could have been anyone, so long as she’s different from Paul.

After all, it’s about Paul and only Paul. It’s about who can help him and how, with no real success at probing the conflicts or systemic issues at hand. Instead, it uses them as bait to reel the film along. When Paul gets beat up early on, a sketchy dude named Lee (McCaul Lombardi, looking and acting exactly as he did in American Honey) takes him in and gets him a job. That “job,” as it turns out, is to intimidate immigrants of color and pocket whatever fees they owe. As is, it’s an extraneous subplot that exists only to run parallel to one of Wye’s struggles. And yes, that struggle is to avoid eviction alongside her family.

Port Authority does this sort of thing often. It just doesn’t do it well. It makes a point of how Wye’s parents kicked her out for being trans, acting like that’s a point of connection with Paul. Of course, his sister isn’t acknowledging him because he’s wayward and seen as a liability of sorts. Wye’s parents disowned her because of her identity. They’re not exactly the same hardships, to say the least, and Lessovitz doesn’t seem aware of this as a writer or director.

[I]t’s about Paul and only Paul. It’s about who can help him and how, with no real success at probing the conflicts or systemic issues at hand.

For her attempts at staging this relationship against the kiki ballroom scene, the setting is skin-deep. For her attempts at tying both trans narratives and stories about the issues immigrants of color face, those facets play more like references than anything else. Hell, the immigration angle doesn’t even play as relevant to the movie as a whole. (It also doesn’t work in Port Authority’s favor that Isabel Sandoval’s Lingua Franca, which also had its festival premiere in 2019, actually understands all of these issues and how they happen to intersect.)

That said, Bloom does solid work for what she gets to do; she definitely outshines Whitehead. The supporting cast of non-actors who play Wye’s family form what’s far and away the most realistic part of the film as a whole, and Matthew Herbert’s score of granulated synths complements and even lifts up Jomo Fray’s cinematography. The overall product is decent on a technical level. It simply doesn’t feel like it understands what it’s trying to say. That is, of course, assuming it knows what it’s trying to say.

Port Authority is now in select theaters and on VOD.