Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableEvery month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. For August, we honor the absurd humor and abject violence of South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook. Read the rest of our coverage here.

In an interview during London’s 2007 Korean Film Festival, made available on the film’s Blu-ray release, director Park Chan-wook said that after filming a sequence of dark, violent films, he wanted to make a movie his daughter could see. I’m A Cyborg, But That’s OK (2006) is a romantic comedy appropriate for kids if you happen to be the daughter of the director of “The Vengeance Trilogy.” Otherwise, this charming wonder tale offers a whimsical, twisted yet mature look at love and compassion.

When the film was released after the successes of Oldboy (2003) and Lady Vengeance (2005), audiences in South Korea were decidedly mixed, according to Park. Some called it a masterpiece, others called it a glaring deviation from a working formula. One thing’s for sure; it’s very difficult to have a lukewarm reception to this truly unusual film.

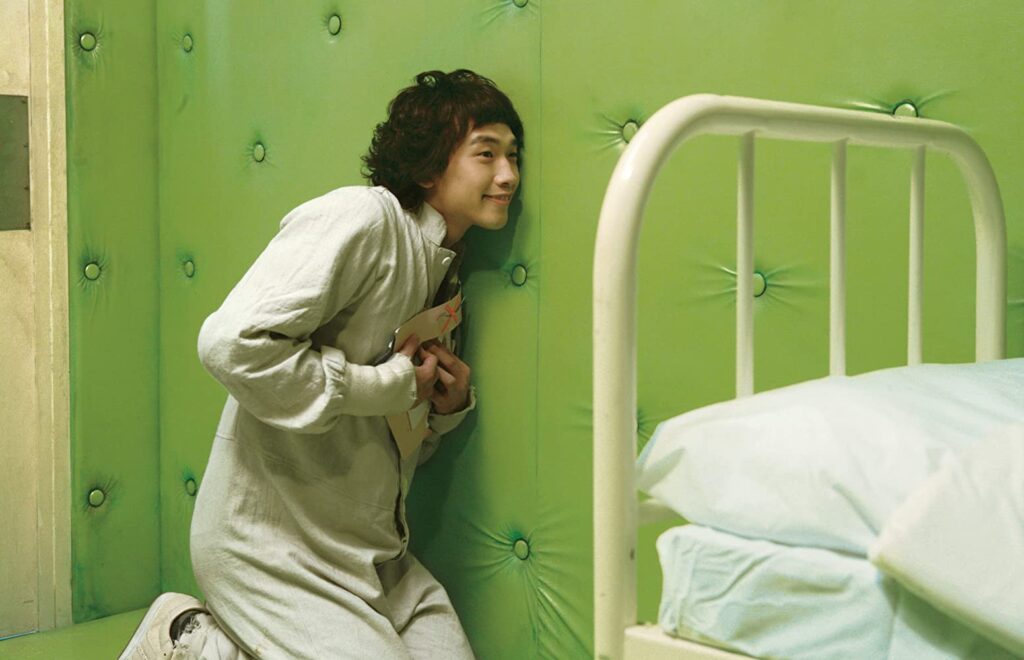

I’m A Cyborg, But That’s OK follows Cha Young-goon (Im Soo-jung), a factory line worker who believes she’s a cyborg. When she is forcefully institutionalized by her family after an episode at work, she must learn to navigate personalities, both human and mechanical, in her new environment. She soon sparks the attention of the kute kleptomaniac Park Il-soon (singer Rain). As Young-goon’s health begins to break down, Il-soon begins a metaphysical journey to connect to and save her.

Like Park’s other films, Cyborg is a visual feast. Ryu Seong-hie ’s art direction is even more explosive than it was in Oldboy. Cyborg has a delightful anime-influenced pop surrealism, with textiles so vibrant they make the eye wander to catch all the little bits of enchantment in the set decoration. The design lifts and extends Park’s quirky mood, so that the quirks feel logic within the world he has created, making it feel rounded and full of depth.

But perhaps the most enchanting aspect of this picture is Im Soo-jung’s performance. Young-goon is a mixture of manic and catatonic, bursting with energy that slowly fades as she rejects human food in favor of licking batteries and other things that might jumpstart her mechanical self. This requires Im to act almost entirely through her eyes, which tell us everything we need to know about what’s going on inside Young-goon’s mind. It’s obvious why Park has called her his favorite actress: her talent, like her character, is extra-human.

For Young-goon’s romantic counterpart, Park chose singing phenomenon Rain rather than a polished film actor. But he meets Im’s talent beat for beat, the two forming a believable and endearing pair. Like Young-goon, Il-soon speaks more with his body than his voice, thanks to Rain’s remarkably nuanced physicality.

Cyborg has a delightful anime-influenced pop surrealism, with textiles so vibrant they make the eye wander to catch all the little bits of enchantment in the set decoration.

Unlike a lot of Western films set in a mental institution, Cyborg is not interested in human vs. institution conflicts. This isn’t an Asian One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, and the girl would have to talk for her to be Interrupted. Instead, we are privy to the patients in their own context, without the medical staff. Without them, we aren’t continually reminded of their abnormality. By excising the clinical aspect from the film, we meet the patients on an even plane where we can observe their world as normal. We can embrace their disharmony and brilliance at the same time.

This leads to a wide array of non-normative possibilities, particularly for the romantic couple at its center. Cyborg is actively interested in finding other ways to connect with and have empathy for others. Denied neurotypical forms of communication, as an audience, the film asks us to consider the things glances, gestures, and gifts say without saying. We must meet these characters on their terms, instead of our own.

So much of Cyborg is about compassion. Meeting the patients as they are helps us reframe their mental health not as a struggle, but as a part of their unique normalcy. The only negative neurotypical voices we hear are from Young-goon’s family, who position her as a dishonorable deviation from an ideal body. This is starkly juxtaposed to the romantic way Il-soon approaches Young-goon. He acts as a model for how we should understand and help others different from us.

Films like Cyborg are a great exercise in changing perception because they interrogate who we see when looking at The Other. Are we seeing our standards, or are we seeing things from their point of view and embracing it as real? Il-soon’s device to help Young-goon is a perfect example: He accepts her reality and works within it to help her, rather than imposing a solution from outside.

The title says it all. I’m A Cyborg, But That’s OK. It’s a camp title, but it rings with truth. This is not a film about correction, but compassion. It’s a wondrous look at the realities that coexist in our world and the magical possibilities that open up when we accept them. Some of us are cyborgs. And that’s Okay!