Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableKinoKultur is a thematic exploration of the queer, camp, weird, and radical releases Kino Lorber has to offer.

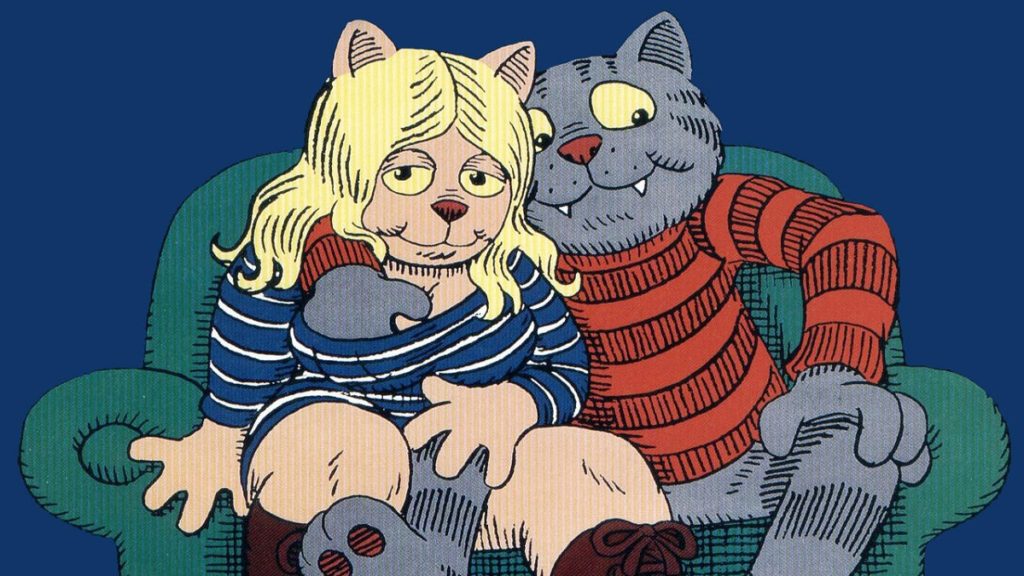

Of the many famous cartoon cats, Fritz the Cat is the horniest. In his two picaresque adventures released by Kino Lorber, Fritz fucks, licks, and sucks nearly every sweet kitty he comes upon. Except his wife, of course.

As animated cinema’s first X and R-rated feature films based on the comic books by Robert Crumb, Fritz the Cat (1972) and The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat (1974) scratch at the boundaries between obscenity and satire. The first is purrfectly perverted, but the second shits way outside the litterbox.

Legendary naughtymation director Ralph Bakshi’s original Fritz the Cat looks back at the supposed “good times” of the 1960s with a biting sensibility that scratches out the eyes of nearly every sacred liberal institution. Fritz is a disaffected college student whose sex-istential and stoned wanderings lead him to all social walks of life. With each encounter, Bakshi highlights the white liberal hypocrisy at its core. Paternalism obscures patriarchy. Intellectualism parades as social superiority. White “racial sensitivity” masks fetishism and self-aggrandizement just as a badge covers abuse of power.

As Fritz gets drawn into the revolutionary underground, he meets Black revolutionaries who both expose and repeat stereotypes within the white liberal imagination. They are as well versed in Black Power critiques of white supremacist image-making as they are grotesquely sexual. When Fritz encounters racial others, there’s a clear attempt by Bakshi to expose and/or reconcile some contradictions and make a political statement, even if it’s just about the nature of contradictions themselves.

(For an in-depth and provocative analysis of Bakshi and his engagement with Black imagery, see “Reckless Eyeballing: Coonskin and the Racial Grotesque” in Michael Boyce Gillespie’s Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film.)

The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat highlights the shallowness of Bakshi’s satirical mind as he continues to portray racist trappings. Picking up a few years after the original and turning its eye towards the newly turned 1970s, Nine Lives finds Fritz a welfare fraud, husband, and father with no future. As his wife nags and kittens cry, Fritz begins to think, “how did I get here?”

So begins a recounting of all the lives he’s lived up till then. We hear about his life during WWII and the 1920s. He encounters a “New Africa” and visits hell. Yet, through it all, neither Fritz nor director Robert Taylor learns the lesson of the first film, which is that successful criticism is achieved through raunch and the grotesque, not because of it.

[The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat] mistakes the source of Fritz’s draw and power, which is not in the grotesque itself but its function — that it is not raunch for raunch’s sake.

Sadly, Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat falls into repeated racist trappings. Where Fritz the Cat commented on the racist images in the American (animated) imagination, Nine Lives merely repeats them. It mocks the South American and Puerto Rican characters with hollow portrayals. It degrades the one-dimensional gay characters.

Bakshi’s original work immediately frames us within a critique of the liberal imagination. It takes time to set up something other than itself. Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat does not. It mistakes the source of Fritz’s draw and power, which is not in the grotesque itself but its function — that it is not raunch for raunch’s sake.

Fritz the Cat deserves its praise and its X Rating. It’s a perverted, explicit, and obscene example of how social critique can happen because of the grotesque. The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat is a sterling example of what can happen if you are not careful and full of care. If one must watch it, watch it in contrast to Fritz the Cat as a reminder of the gulf we can find ourselves when we misuse the grotesque.