Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableThe writer/director’s take on Priscilla Presley’s relationship with Elvis is a wise and unsensational tale of growth despite its larger-than-life origins.

This piece was written during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the works being covered here wouldn’t exist.

As daybreak bleeds from within the walls, Priscilla Presley (Cailee Spaeny) wakes up next to her husband, Elvis (Jacob Elordi). Her water’s broken and, as he calls for a car, she goes to the bathroom, where she applies the perfect fake eyelashes in silence.

This is about halfway through the film. Writer/director Sofia Coppola has had a predilection for these moments unstuck in time throughout her career. A wordless miscarriage reveal in Marie Antoinette, the protracted, dissociative opening of Somewhere, a quiet, one-take robbery buried among the overstimulation of The Bling Ring. With this moment, Priscilla modestly sits among them.

It does so because while her latest is very much her own, it’s also one of her most accessible. Carrying a sense of agency even as its heroine struggles to secure hers, Coppola fleshes out a straightforward narrative with such visual moments of insight. Those lashes carry a sense of pretense. Coppola strips them down and helps grow the girl behind them.

Opening in 1959, Priscilla Beaulieu is a 15-year-old living in Germany with her mother (Dagmara Dominczyk) and stationed U.S. Army stepfather (Ari Cohen). She meets Elvis at a party. While ten years his senior, he instigates a courtship. She has a crush on him, sure, but he’s an up-and-coming idol; she’s a high school freshman. From his hanging on her age in disbelief to her naïveté, the film establishes this dynamic expeditiously and tactfully.

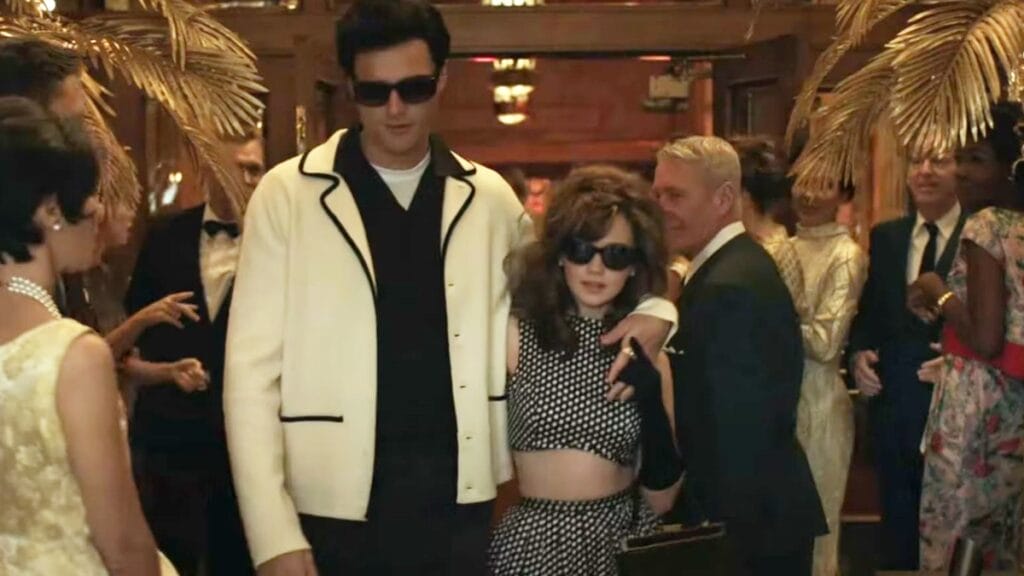

His height towering over hers could border on hyperbolic, given how the movie frames the two, but he’s a man and she’s a girl. They go on a few dates. He invites her over to Graceland. He welcomes her toward shifts in aesthetics and attitude that, across her transition into womanhood, preclude much growth of her own. All the while, Coppola circumvents the sensationalism this story could have succumbed to.

Her script—adapted from Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me—recounts their relationship as detached from either party’s person. The allure is a mix of art and stardom, not specifically his. They discuss popular music, but his involvement is more incidental. On an early date of theirs, Elvis takes Priscilla to see Beat the Devil, reciting Humphrey Bogart’s dialogue in real-time. He declares his admiration for the likes of Marlon Brando. Even a large part of him, the recent loss of his mother, relies on someone else rather than himself. “He’s grieving,” Priscilla declares to her parents in his defense.

Coppola fleshes out a straightforward narrative with…visual moments of insight.

This Elvis isn’t particularly a star, but Coppola’s main effect here isn’t deconstructing his legacy. This Elvis isn’t evil, either, despite his actions. In a lot of ways, he’s worse: small, oversensitive, and hurtful. He depersonalizes himself to Priscilla on a running basis to maintain his stature, not through allure but with an idea of it. The shadow of grief and the love of others’ work rather than one’s own make him easy to fall into.

Selflessness is one thing. Elvis’ lack of self is another entirely, and Priscilla’s devotion to him remains largely disembodied because it has no real target. She changes her looks to please him, but he never allows her to actually do it for him. Her efforts are so often for no one, herself included, and Coppola’s understanding of such is what conveys such danger. As for the alcohol and drug use that Elvis leads Priscilla toward—well, that’s just an extrapolation of such.

Aside from Coppola’s requisite, dry sense of humor, little here titillates, and by design. Priscilla marks her third collaboration with Philippe Le Sourd, and his digital cinematography lends a modernity to the film without reading as playful or distracting. Rather, it’s crisp and easy to fall into, finely capturing the respective production and costume designs of Tamara Deverell and Stacey Battat. All that said, none of Elvis’ music features here.

The filmmakers couldn’t obtain the rights and perhaps for the film’s betterment, as the existing soundtrack generally avoids a literalism it could have strayed toward. Tied to the era but never stuck to it, Coppola and music supervisor Randall Poster opt for anachronisms but lightly. This isn’t Marie Antoinette in its level of dissonance between subjects and sounds. It is a nice way to inject a contemporary feel into a timeless work, though, and it’s a rather lax one. Meanwhile, the editing from Sarah Flack, who’s worked on all of Coppola’s features sans The Virgin Suicides, maintains an extemporaneous momentum because it so often operates at the rhythm of the performances.

By Priscilla’s end, she’s gone from 15 to 27. Spaeny, who was 22 during shooting, centers about as much of the film as Coppola does. Her onscreen growth is almost a wonder to behold. It’s one thing from a technical standpoint, Jo-Ann MacNeil’s makeup design included. It proves another from its star, who constantly calibrates her performance as someone not just realizing her growth and identity but the very idea of such. It’s not simply her idea either, but someone else’s as well.

Because, again, this Elvis isn’t evil. He’s hurtful. And that hurt goes unnoticed: it shimmers and shines and rots, owning the light from the walls that house it. Coppola and Spaeny never lose sight of the universality at hand here. All things considered, Priscilla does have some pacing issues by its final third, and perhaps some of its needle drops are too on the nose. Nevertheless, all its ingredients form something very full from the inside out.

Priscilla reports to Graceland, and theatres, on November 3.