Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableDay 2 of Chicago’s documentary film festival displays films about iconic journalist Mike Wallace and the trials and tribulations of a family struggling to provide private EMT care in Mexico City.

While Knock Down the House opened Doc10 2019 with a droll mix of pluck and perseverance, the next night brought us a smörgåsbord of hard questions. In Mike Wallace is Here, that main question was, “Why are you such a prick?”

It might be hard to level one of our time’s most prolific news personalities with such a proposal, but that curtness isn’t to totally out of left field. It’s also the framing device for Avi Belkin’s documentary, quickly introducing us to its subject‘s demeanor, warm enough to soothe his interviewee and just scalding enough to wound them at the ankles. What starts out like a greatest hits compilation of his zingers soon turns into a retrospection on his career and life.

“What do I have to look back on?” he asks at one point with his sage, sinewy delivery. According to the film, that would be his insecurities—the pathological need to ask others about himself while framing the questions as about someone else. As he interviews Barbra Streisand, Vladimir Putin, Eleanor Roosevelt, and more, the film puzzles his work together with a technical wit and grace. It can be amusing, too, as Belkin and editor Billy McMillin glide through his own work’s motifs.

But despite the shallower entertainment of its first half-hour, the film reveals itself to have a deeper infatuation with forging one’s legacy, both within and divorced from Wallace’s own life. The general throughline of his career from the mid 20th century to early 2010s is swift, playing hopscotch on our ideations of and iconographies—be they political or pop-cultural—of the past.

However, this works best when the film resists its more obvious impulses. Mike Wallace is Here has a tightly coiled momentum for stretches that get sabotaged by its more topical aspirations. (Hey, isn’t it weird to see stuff that Donald Trump said in the ‘80s? Don’t worry; the movie will make sure you know.) When Belkin continues on the straight-and-narrow, he creates a stolid stream of consciousness. When he gets sidetracked, the movie begins to feel like a rough edit.

The central thesis of Wallace’s inability to live without implicating others is empathetic, but the movie has more than a few asides that don’t quite mend his personal and professional lives as intended. There’s an anxiety throughout Belkin’s picture about our collective legacies and how precarious thoughts can turn into something much more omnipotent in hindsight, but Mike Wallace is Here too often feeds into itself. Its Mirror-like structure works the best. It’s a bit maddening when it seems to fight against itself.

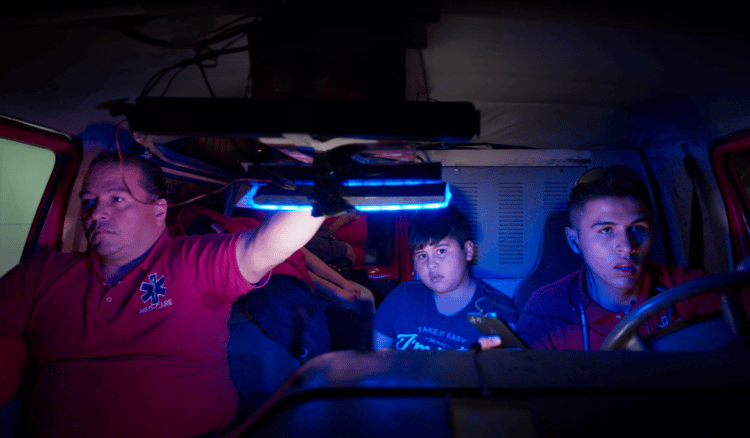

But while Mike Wallace might sometimes feel like a Robert Redford character come to life, the idea of living through one’s work takes a very different appearance in Midnight Family. Luke Lorentzen’s second feature follows the Ochoa family, who run a private EMT service in Mexico City. Did you know this was a thriving business? Because I sure didn’t, and it’s in turns exciting and exasperating to watch 17-year-old Juan try to save critically injured patients across the cities because the government is egregiously ill-equipped.

As briefly explained through opening title cards, there are over 9 million citizens in the city, all of who have to share 45 official ambulance networks. The rest are, like the Ochoa’s, unofficial: privately owned and operated rescue vehicles that operate on the fringes of the law. Legality, however, doesn’t correlate to morality. This family is morally obligated to help those in need, but they also need to get their own money for gas, food, and bills.

The cinéma vérité approach does strong work at establishing the familial dynamics, and by focusing on Juan as the human core, the film really lets their environment breathe. There’s a jewel-toned abrasiveness to the city streets that feel cinematic and grounded in actuality. Some scenes, however, trade in luminance for sickly fluorescence, tinged in adrenaline despite its pointedly cyclical structure. It mostly pays off, even if its depth of field is quite distracting.

It often feels just on the edge of dehumanization, and tragically so. Lorentzen’s direction and editing rarely give any faces to the wounded. If the film reveals someone’s fate, it does so with a stark matter-of-factness. If it doesn’t, it probably didn’t matter much anyway. But while that sounds crass in theory, Midnight Family is so attuned to its moral ambiguity that it’s hard to fault anyone onscreen. They’re all just trying their best.