Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableKyle Edward Ball’s feature debut is slow, but pays off in perfectly capturing the dark nothing of childhood fear.

I was a fretful child who was scared of her own shadow. A victim of an overactive imagination fed by parents who didn’t monitor what I read or watched, there wasn’t one thing I was particularly afraid of, it was all things. Vampires, werewolves, serial killers, alligators in the sewer, Michael Myers, they all lurked in the recesses of my mind, waiting to jump out at me when I wasn’t paying attention. Luckily I was always on high alert: I never slept in complete darkness or silence, and, much to my mother’s chagrin, I kept both my closet and the space under my bed stuffed full of clutter so there’d be no place for the monsters to hide. Even then, I always jumped in and out of bed far enough away that nothing could drag me underneath. The way I saw it, you just couldn’t be too sure.

I’m the target audience for Kyle Edward Ball’s experimental film Skinamarink, and while it’ll undoubtedly be one of the most polarizing horror movies of 2023, I appreciate its singular commitment to depicting the hazy, unfocused feeling of childhood fear, when the safest place in the world suddenly feels unfamiliar and dangerous. Very little actually happens in it, but its menacing vibe slowly moves down your spine, leaving you with the same disorienting sensation as being woken up out of a dead sleep by a strange noise.

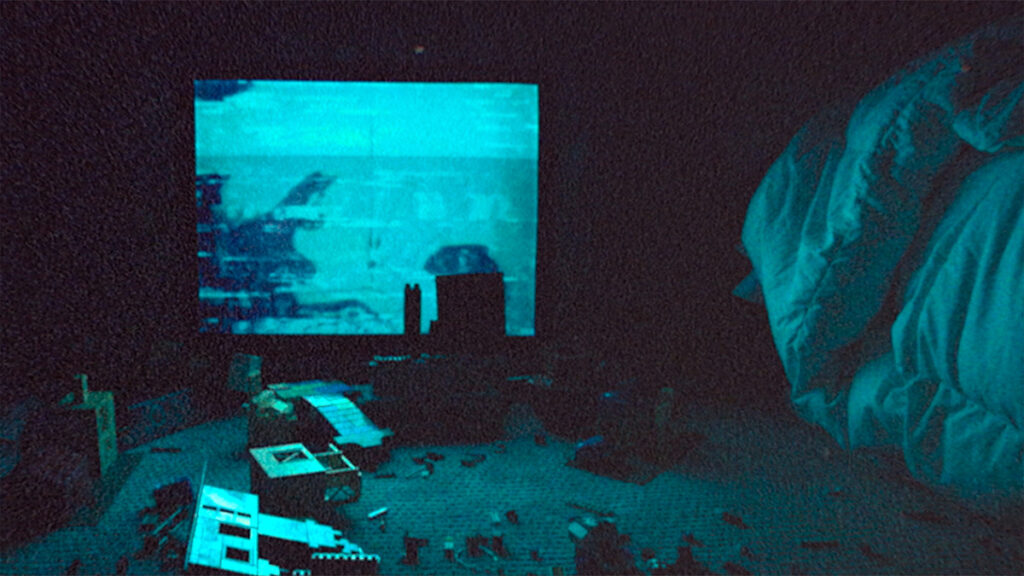

Normally two to three paragraphs would be expended on a plot overview, but there really isn’t one. Nor are there really any characters, except for two small children, Kevin (Lucas Paul) and Kaylee (Dali Rose Tetreault), who we sometimes hear, but never see, except for quick glimpses of their pajama-clad legs. The siblings wake in the middle of the night to find their father gone (their mother is already gone, possibly dead, it’s unclear), and all the windows and doors leading to the outside of their house have disappeared, trapping them inside. Understanding, like most children do, that the best thing to do in such a situation (strange as it is) is wait for an adult to come, they remain inside their house passing the time by watching old cartoons, even as it becomes an increasingly hostile and scary place. Things slither and move around in the dark, and a ghostly voice beckons them to come upstairs. Their parents are gone, but they aren’t alone.

According to a title card, Skinamarink takes place in 1995, but it has the grainy, washed-out look of something made in 1975. It’s a smart choice on Bell’s part, because the Super-8 style quality makes it look like there’s constant movement along the edges of the screen. In some of the darker scenes, the air itself seems to be vibrating, as if the entire house is coming alive. Bell makes another clever choice in using his actual childhood home as the set for whatever terrible things befall Kevin and Kaylee (or not, it may just all be a nightmare too, we’re never quite sure). The whole thing feels personal, a trip through Bell’s memory palace of all the things that scared him when he was little, even if by daylight there would have been nothing there at all.

It reminded me of staying over my grandmother’s house as a little girl, and watching the shadow of the tree outside the spare bedroom stretching across the ceiling, the branches like long, reaching fingertips. It was an old house, and it creaked and groaned throughout the night, because no house is ever completely silent. “It’s just the house settling,” my grandmother told me, trying to be reassuring, but it didn’t help. It made it sound like we were inside a living thing, and it was shifting around and trying to get comfortable before deciding to swallow us whole.

As mentioned, Skinamarink’s lack of action and ambiguous ending are going to send fickle horror fans running for the nearest angry Reddit thread to declare it the worst movie they’ve ever seen, a scam pulled on gullible audiences. Well, call me gullible then, because while it’s not scary, exactly, it is sinister, like a cursed movie within a movie that a character watches before they’re killed a week later when an air conditioner falls on their head. Certain moments, like a disappearing toilet (complete with dramatic stinger) are silly at face value, but it adds to the overall sense of unease, and the desire to know just what the hell is happening here? Other scenes, such as a long shot of a nearly pitch black doorway, are so effective that they raise goosebumps. But there isn’t anything there, you might say. Oh, but there is. Darkness is there.

I fully expect Skinamarink to be dissected, and each scene carefully analyzed to point out what is and isn’t there, much like how viewers painstakingly found all the hidden ghosts in Mike Flanagan’s take on The Haunting of Hill House. Try not to do that upon first watch. Just take it in as a wholly unique experience, from a filmmaker who remembers what it’s like to believe in monsters under your bed, and knowing that they’re watching, and waiting.

Skinamarink opens in limited theatrical release January 13th, & premieres on Shudder later this year.