Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableIf you walk into Magellan expecting a Filipino Master and Commander, you will walk out disappointed. The story of the famed explorer has all the makings of an historical epic. Years on the high seas. Monumental firsts. Violence, tragedy, and retribution. But that’s not the story writer and director Lav Diaz is interested in telling.

Diaz, one of the most prominent practitioners of slow cinema working today, manages an impossible feat instead. He expands the story of Magellan while shrinking the man at the same time.

The film follows the explorer from the shores of Malacca, Malaysia in 1511 through his crossing of the Pacific to, finally, his arrival and brutal death on the island of Cebu in the Philippines in 1521. However, Diaz opens and closes the film by focusing not on Magellan himself but rather on the indigenous populations that encountered him.

Though it may be Diaz’s first film not in his native Tagalog, it remains a thoroughly Filipino picture. Magellan depicts the enormity of the world, full of people with their own lives, customs, and concerns. That stands in contrast to how little the explorer actually understood of it, and the pettiness and minor nature of Spain’s mission.

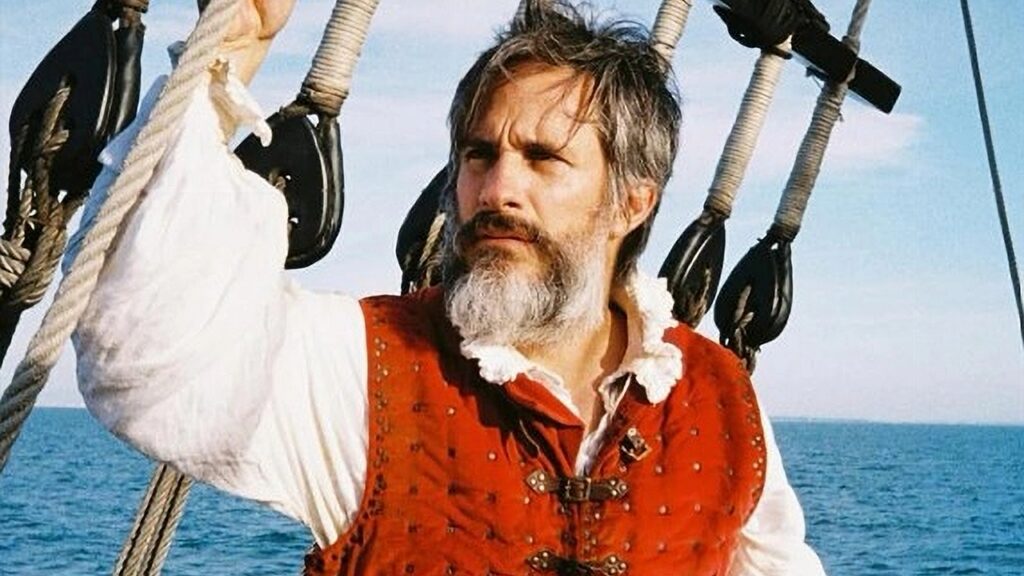

At 5’7”, Gael García Bernal is hardly towering in stature to start with. Still, Diaz does his best to dwarf the character at every turn. The costuming cuts García Bernal off at the knees with tall boots that swallow his legs and heavy, draping fabrics that encase and overwhelm. And it’s not just the actor that Diaz shrinks, it’s the explorer’s entire venture, his very ambition. The way each scene is shot is a magic trick of the eye. For instance, lose-ups and medium shots frame small rooms with low ceilings. That makes a party of 10 look jam-packed and sparse at the same time. Cheers of “Land ho!” intentionally lack weight, sounding more like two drunkards yelling “Woo!” in an empty bar than victorious celebrations. Even the ships themselves give the impression of miniatures, as though the entire production were shrunk down to fit in Diaz’s pocket.

The lack of grandeur benefits the dreamy, sleepy pace. The score is nonexistent, leaving only the sound of water—rain, waves, rivers, oceans—to soundtrack the film’s 160-minute run time. It has the unfortunate effect of acting as a bedroom sound machine, making it hard for eyelids not to droop. One gets the sense that Diaz almost wants viewers a little bored, guiding their attention from Magellan’s self-importance to get lost in the wider world on screen.

There’s something a little poetic about the difficulty of the story not being in the violence, brutality, or inherent cruelty of imperialism, but in merely spending time with the story itself. Populated with bodies, the film nonetheless doesn’t linger on them or emphasize the carnage. They exist as plain fact, not to horrify or titillate.

Where Magellan falters is in its episodic nature. While it mostly works well, the trouble comes when Diaz shifts the story to the indigenous peoples. You get the feeling that you’re missing context. The desire to separate those stories so wholly from Magellan is understandable, but it makes the narrative feel disjointed. In a movie that’s almost certainly going to be a bit of a struggle for the average viewer already, any additional stumbling blocks in the story are going to hit a harder.

Magellan is a difficult watch by design, but one worth lingering over. There’s a beauty in an historical epic that removes the epic from the equation. Once you strip that away, it feels like a truth laid bare, and that makes the effort it will take to watch it worthwhile.

Magellan sails the ocean blue into American cinemas on January 9.