Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableRyan White’s documentary examines the two women who killed Kim Jong-un’s brother, and the complex web of lies and deceptions that got them to do it.

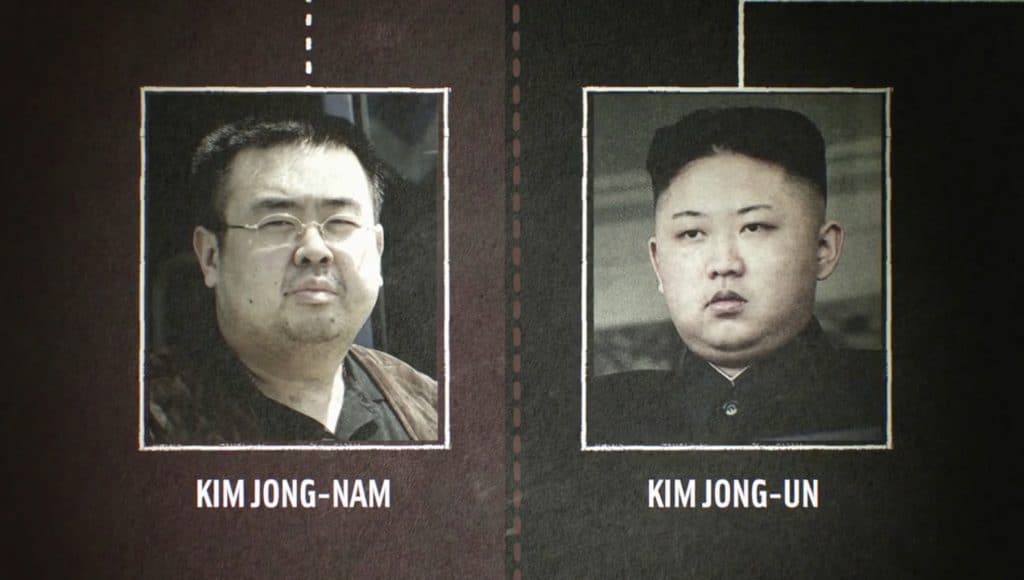

In February 2017, Kim Jon-sam, the brother of Kim Jong-un, was walking through a Malaysian airport. Preparing for a flight back home to China, Jon-sam was suddenly hit with a substance by two women. Shortly after, Jon-sam developed a limp, went unconscious, and was dead within an hour. The brother of North Korea’s leader had died through exposure to a nerve agent called VX, one of the deadliest toxins on the planet.

The documentary Assassins chronicles the trial of the two women responsible for his death, Siti Aisyah and Đoàn Thị Hương. The Malaysian government views the duo as trained killers working directly with the North Korean government. But director Ryan White uncovers something more complex through interviewing local journalists and the lawyers tasked with defending Aisyah and Thị Hương. Turns out these two women were under the impression they were on a Jackass-style prank show, not engaging in an assassination.

Though its real-life story is full of unbelievable twists and turns, Assassins is no comedy. The project establishes an appropriately ominous atmosphere right from the get-go. The very first scene depicts security camera footage of Jon-Sam’s exposure to VX alongside audio of news reports covering the event. After establishing how this scenario has traveled around the globe, White spends much of the rest of the movie indulging in a more intimate approach with the chronicling of Aisyah and Thị Hương’s legal battle.

Interviews with the two women’s friends and family make it clear the humble origins they came from. Rather than being North Korea’s answer to Jason Bourne, they were both cash-strapped twenty-somethings frequently at the mercy of greater forces. For instance, Aisyah’s plight involved being forced into sex work, which reflects the struggles facing so many migrant women in Malaysia. Both these ladies thought this prank show would help them break free of poverty. Instead, they once again found themselves as pawns in larger circumstances.

Extended interviews with Washington Post writer Anna Fifield, an expert on North Korea, lend sufficient context to how the manipulation of Aisyah and Thị Hương plays into Jong-un’s larger plan. Daunted by the pressures of being a younger ruler of North Korea, he chose to take extreme measures to assert his authority. The death of his brother, the one who was once supposed to be the heir to North Korea’s throne, appears to be the latest example of Kim Jong-un flexing his political prowess.

This information provides interesting revelations regarding the mindset of the Korean dictator, but their presence has its drawbacks. White bounces back-and-forth between extended explanations of North Korean politics and the story of Aisyah and Thị Hương, which keeps the doc from focusing too well on one thing. One gets so immersed in their courtroom struggles that anytime Assassins cuts away, the ensuing sequence registers as an annoying distraction rather than a welcome dose of education.

There’s no justice here, just the ever-grinding wheel of corruption.

By the end of the movie, I was also left wishing we got more interviews with Aisyah and Thị Hương themselves. Everyone on-screen keeps talking about these two women but they’re given few chances to speak for themselves. That’s particularly discouraging since hearing them speaking for themselves provides some of the most impactful moments of the project. The snippets we hear from them describing their experiences in prison, for instance, are so harrowing that one wonders why Assassins is bothering to talk to anybody else.

As the two women describe how they had nobody but each other in their time of isolation, Assassins slowly but surely reveals its central theme. This isn’t a documentary just about the murder of Kim Jong-Sam. Much like Chernobyl, the doc chillingly depicts how countries are willing to sacrifice people in the name of maintaining their image. This is epitomized in one interview subjects offhand remark that “It wouldn’t look good for someone so important to be murdered in a Malaysian airport” in regards to the death of Kim Jon-San.

This is why Aisyah and Thị Hương face a death sentence. Not their guilt, not evidence, but for PR and Malaysia trying to maintain a solid relationship with North Korea. The fact that Aisyah and Thị Hương are not native to either Malaysia or North Korea adds an extra layer of tragedy to this exploration. In the eyes of these world leaders, foreigners are disposable tools, not human beings. It’s a trait that, unfortunately, is not exclusive to just the countries at the heart of Assassins, which lends a universal sense of anguish to the proceedings.

The way human beings are at the mercy of larger countries manages to creep into the eventual resolution to Aisyah and Thị Hương’s sentences. The tidy wrap-up found in many courtroom dramas is absent here. Instead, Assassins leaves the viewer keenly aware of all that Aisyah and Thị Hương have lost, and how little the powerful paid. There’s no justice here, just the ever-grinding wheel of corruption.

By the end, Assassins offers no easy answers, on top of a sense that the story it’s telling is far from over. Though its reach sometimes exceeds its grasp, it remains a deeply human and rage-inducing documentary.

Assassins is currently playing in select theaters, and comes to VOD January 15, 2021.