Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableThree of the festival’s docs explore critical figures in art and academia—to varying results.

These days, celebrity-based documentaries, especially the ones that eventually find a place in the Sundance lineup, tend to fall into one of two categories—they either serve as cinematic victory laps for proven successes, or they work as reclamation projects serving to expose the legacies of their subjects to new generations who may not realize their importance. Three of the titles in this year’s documentary selection, Lisa Cortes’s Little Richard: I Am Everything, Anton Corbjin’s Squaring the Circle (The Story of Hipgnosis), and Nicole Newnham’s The Disappearance of Shere Hite fall into the latter category and go about their cultural rehab efforts with varying degrees of success.

Considering the way that he blurred gender, racial, and musical lines with his groundbreaking work as one of the true pioneers of what would become known as rock’ n’ roll and his outre personality—especially considering that he was doing all of it at a time when such things were deeply frowned upon by the establishment—a documentary on Little Richard, who died in 2020, covering both his considerable artistic contributions and the equally pronounced contradictions in his personal life would seem to be a no-brainer.

Using a combination of archival materials and talking head interviews with friends, family, and famous faces (including Mick Jagger, Tom Jones, and Nona Hendryx), Cortes’s film charts the life and career of the man born Richard Wayne Penniman from his early days as the son of a Georgia minister to his success in the 1950s with such lasting favorites as “Tutti Fruitti,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Good Golly Miss Molly“—tunes that scandalized many but which were celebrated by rebellious teenagers (including John Waters, who admits that the pencil-thin mustache that he has sported for decades was grown in homage to Richard’s).

I Am Everything continues through the ups and downs of the Sixties and Seventies and his resurgence in the 1980s, when his cultural legacy finally began to find widespread acceptance—as an artistic influence, as a Black man, and as a gay man (albeit one who wrestled with his sexuality for decades), though never as much as he felt he rightly deserved.

For those who have little to no working knowledge of Little Richard other than hearing his songs on an oldies station or dim memories of his hilarious supporting turn in Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills (which helped fuel his cultural comeback), I Am Everything will serve as a decent introductory primer to the man and his legacy. On the other hand, those who are already familiar with him and are looking for a more penetrating look at his life are likely to become frustrated with how the picture shies away from probing too deeply into specific areas.

When it comes to making a case for his music—the easy part—I am Everything does a decent job of capturing the genuine shock and outrage that drove Little Richard’s work (which can still be felt today). His anger at how the music establishment tried to tamp it down over time, most notoriously when Pat Boone recorded cover versions that outsold Little Richard’s originals because they got better airplay and promotion.

When it comes to taking on Little Richard’s personal life, though, the film proves frustrating. While it does touch on his conflicted stance on his sexuality—although he once described himself as “omnisexual,” he would at times publicly denounce homosexuality, calling it an “unnatural affect” as late as 2017—it doesn’t go into it in any real detail (there are no interviews with any of his male partners) while other darker aspects of his life are either dealt with obliquely (it is noted that he was dismissed from Oakwood University, the religiously-oriented college where he enrolled in 1957 but it doesn’t mention that it was for exposing himself to a fellow student) or almost completely ignored, most conspicuously his 1962 arrest for voyeurism.

When it comes to taking on Little Richard’s personal life, though, the film frustrates.

Cortes seems to recognize the conflict running through Richard’s life—at one point, he is described as being “a man very good at liberating people and not so good at liberating himself”—but she never seems willing to press any of her interview subjects on potentially contentious issues, whether regarding Little Richard’s personal life or the lack of acknowledgment of his cultural and social influence on the musical genre that he helped to create. There is a great, profound, and provocative film to be made on the life and lasting legacy of Little Richard—alas, Little Richard: I Am Everything is not that film.

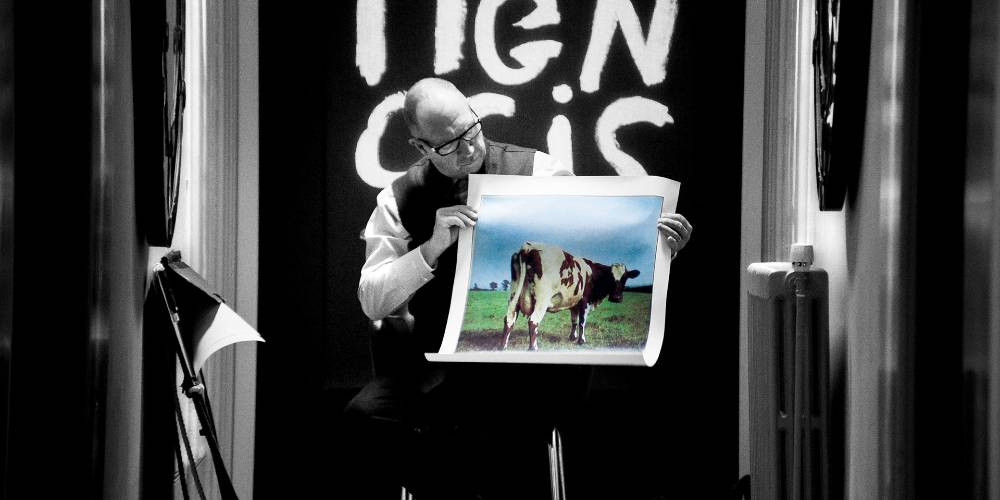

Of course, anyone with even a mild interest in the history of rock music is presumably familiar with the likes of Little Richard. Still, even the hardcore fans might blank if you asked them to identify Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell or their contributions to the genre. Even if the names don’t ring any bells, they are no doubt familiar with their work because the two, the founders of the design studio known as Hipgnosis, designed some of the most iconic album covers of all time—Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here, Paul McCartney and Wings’s Band on the Run, Led Zepplin’s Houses of the Holy and Peter Gabriel’s first three solo albums.

After meeting at a London house party in the late Sixties that ended in a drug bust, photographer Powell and designer Thorgerson went into business at just the moment when album cover art was shifting from just an unassuming photograph of the performer to more elaborate artistic expressions that were meant to complement the musical narrative found inside. As the Seventies progressed and their audacious concepts found their way onto some of the biggest albums of that era, Hipgnosis became an enormously successful undertaking, and their projects grew in size, scope, and cost.

Inevitably, Hipgnosis found itself touched by the same problems that faced so many of the era’s bands as a once-thriving partnership fell victim to greed, creative differences, and wretched excess that brought the studio to an end in the early 80s, just before the advent of CDs made elaborate album covers a thing of the past.

Considering Corbjin’s history as a designer and photographer of rock acts—he did the cover for U2’s The Joshua Tree, for starters—it is not surprising that his fascination with the subject at hand can be felt throughout Squaring the Circle. However, the film suffers from a critical problem: it formulaically recounts the story of a genuinely groundbreaking artistic concern. The film utilizes the standard template for movies of this sort—archival footage of varying degrees of significance, talking head interviews, and loads and loads of needle drops from the albums they worked on. While the talking heads that Corbjin was able to round up are impressive—McCartney, Gabriel, Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Nick Mason, and Noel Gallagher, the latter speaking only from a fan’s perspective—and the tales they tell (ranging from the excesses that went into a thoroughly undistinguished Wings greatest hits album to how the giant inflatable pig for Pink Floyd’s Animals cover slipped its tether and flew away during the photo shoot) are amusing but not precisely probing.

Considering Corbjin’s own history as a designer and photographer of rock acts—he did the cover for U2’s The Joshua Tree, for starters—it is not surprising that his personal fascination with the subject at hand can be felt throughout Squaring the Circle.

While the interviewees’ star power will no doubt ensure that the film will get picked up for distribution, they, unfortunately, make the comments from Powell himself (Thorgerson died in 2013) seem almost like afterthoughts at times. Hardcore rock fans will no doubt enjoy this warm nostalgia bath (and delve into their record collections to see how many Hipgnosis creations they have). At the same time, those less involved will probably find it pleasant but forgettable—the exact opposite of the typical Hipgnosis creation.

Although the title makes it sound like some true-crime narrative, The Disappearance of Shere Hite chronicles the life and work of a woman whose name and legacy have largely been cast aside even though she had been an enormously famous and controversial figure during her heyday and that the pinnacle of her accomplishments, the 1976 book The Hite Report on Female Sexuality, not only broke new ground in the study of female sexual behavior (an area that had been all but ignored up until then) but remains one of the biggest-selling books of all time.

Newnham follows Hite’s story from her childhood to her grad student studies at Columbia, where she questioned long-held and male-dominated views on sexuality. This led to her sending out questionnaires to a broad spectrum of women asking them to share their feelings and opinions wholly anonymously (which would hopefully encourage more honest responses). Hite compiled those responses in The Hite Report on Female Sexuality. It became an instant best-seller that wound up making Hite a celebrity to boot.

However, controversies surrounding her methodology, a growing sense of conservatism in the land due to the death of the counter-culture and the subsequent Reagan Revolution, and straight-up sexism from people who were shocked and appalled that not only was a woman challenging the then-accepted norms and findings on research on sexuality, she was making the audacious suggestion that women could provide their sexual pleasure rather than being reliant solely on male penetration. This inevitably led to charges of man-bashing (which intensified with her follow-up book, 1981’s The Hite Report on Men and Male Sexuality) and to such overt sexist vilification in the media that Hite ultimately left the country. Her work slipped into obscurity.

Hite passed away in 2020, but thanks to the press interviews and media appearances she gave during her heyday, Newnham can show Hite discussing and defending her work and illustrate the condescending ways in which others tried to dismiss her efforts. (Even Oprah Winfrey joined the fray at one point with an episode of her show consisting of Hite facing a hostile all-male audience, few of whom seemed to have read her work.) Newnham is also able to fill in some of the gaps by having Hite’s notes and writings read on the soundtrack by Dakota Johnson.

The resulting story is equal parts fascinating and enraging and fits quite nicely alongside recent documentaries dedicated to exploring the lives of culturally vilified women like Pamela Anderson and Britney Spears. If The Disappearance of Shere Hite has a flaw, it is that while it goes into great and rage-inducing detail about the indignities that Hite faced as a result of her work (including a cringe-inspiring ambush interview at the hands of Maury Povich), it, unfortunately, skimps in regards to the one area of her work where good faith critics might have had a point—the exact details of how she extracted and interpreted the data she received from their respondents. Nevertheless, The Disappearance of Shere Hite is an informative and entertaining documentary that offers a much-needed reappraisal of Hite and her trail-blazing work that will hopefully expose her contributions to the field of human sexuality to future generations.