Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without Cable(This dispatch is part of our coverage of the 2019 Chicago International Film Festival.)

Welp, CIFF keeps chugging along, and the weather just keeps getting colder. Still, there are plenty of cinematic offerings on display to keep you braving the cold, even as they offer some chilling portents for awards season moving forward.

First up is the highly-anticipated Jojo Rabbit, the latest from Kiwi comic genius Taika Waititi (What We Do in the Shadows, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, Thor: Ragnarok), a charming-if-somewhat-anodyne Nazi comedy about a 10 year old Hitler youth (Roman Griffin Davis), crippled after an accident at Nazi camp, finds himself forging an unlikely partnership with a young Jewish girl (Thomasin McKenzie) his compassionate mother (Scarlett Johansson) is hiding in their annex. Much ballyhoo has been made about whether or not Jojo Rabbit has enough teeth to justify its premise — some have derided it as a “hipster Nazi comedy” — but I think there’s merit to be found among the mess.

Jojo‘s biggest problem is that it can’t quite settle on a tone, a barometer for how cheekily to treat the Nazi radicalism at its heart. When it works, it’s a bittersweet coming-of-age story about a young boy being slowly deradicalized from fascism by sheer exposure to the very thing he’s being taught to hate. Davis and McKenzie are particularly lovely, the former’s adorable naivete offering a child’s-eye view of tyranny while McKenzie finds droll strength in a role that could be fairly passive. Johansson, to her credit, is also mesmerizing as a great mom who also works to find the sunny side of the darkest time in human history.

But then Taika shows up as a goofy, bug-eyed ‘invisible friend’ version of Adolf Hitler, and Jojo loses whatever momentum it had up to that point. His appearances are brief but grating, and they feel redundant – we don’t need to see Jojo fighting back against the version of Hitler that’s in his head to feel his deprogramming taking hold. It feels like an instance of the filmmaker getting in his own way. As a director, he’s stellar; as a comedy actor, he’s lovely. But here, he paradoxically feels mismatched with the material. More detailed thoughts will come as the film nears release, but so far, Jojo is an interesting mess that can’t quite find the bite in its satire.

Where Jojo‘s flaws are in the filmmakers’ confusion over its tone, A Girl Missing (Japanese title: Yokogao, or ‘side profile’) stumbles in connecting its myriad narrative dots. A twisty, convoluted thriller about a hospice nurse named Ichiko (Mariko Tsutsui) who finds herself inadvertently involved in the week-long disappearance of one of her charge’s granddaughters, A Girl Missing refuses to hold your hand through its deceptively bifurcated timeline (a hint going in: the film flits between Ichiko’s life at two different points). Kōji Fukada, a filmmaker known for his opaque, subtly textured dramas, is certainly in his wheelhouse here, laser-focused on telling the story of a woman undone by crimes she didn’t even do.

The problem is that, even for seasoned arthouse viewers, the narrative is challenging, branching off into a million directions that only eagle-eyed people (and those willing to fill in more than a few blanks themselves) will be able to pick up on. Apart from the main story of Ichiko’s guilt, there’s also an erstwhile forbidden romance between Ichiko and the disappeared girl’s sister (Ichikawa Mikako), a far-flung timeline in which she pursues and romances a hairdresser (Ikematsu Sosuke), and dreamlike asides where she wanders through the streets acting like a dog. Fukada films these moments with equal weight and no small amount of distance, refusing to signpost where to focus and what elements deserve the most attention. It’s certainly bold, assured filmmaking, but you’re too busy putting together the jigsaw puzzle of the plot to appreciate these elements on a second viewing. To its credit, Tsutsui offers a layered, enigmatic performance that almost makes the confusion worth it.

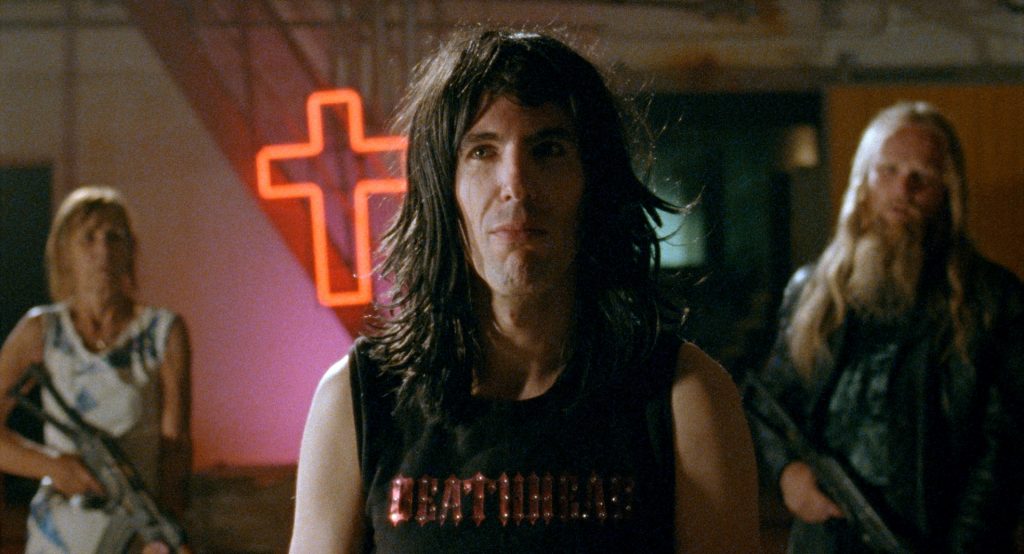

Let’s keep with the confusion angle, but get a little goofier with it — Miguel Llanso‘s quirky, nostalgia-fueled midnight-movie special Jesus Shows You the Way to the Highway. Everything and the kitchen sink is thrown in here, from kung fu sequences with people in ’60s Batman outfits to Afrofuturism to Danger 5-style low-budget lampooning of ’60s spy flicks. The story, such as it is, involves a CIA agent with dwarfism (Daniel Tadesse) diving into the Matrix-like cyberworld of a CIA computer to fight a deadly Soviet virus called “Stalin”, and dives further down the rabbit hole from there.

Anything and everything is thrown at the surreal wall to see what sticks, and the ensuing gumbo certainly has its own gonzo appeal. It’s goofy and irreverent and quickly hops from one sequence to the next, as if Llanso knows that his gags only have so long a shelf life. And yet, in the final stretch, it all somehow manages to land together in a sort of narrative consistency, which itself is impressive. Still, that’s elementary: see it for its oddball aesthetic, a stew of Apple II computers and landline telephones, with virtual-reality ‘avatars’ that are just people in animated paper masks filmed in stop motion, an arresting technique I’ve never seen before. It doesn’t elicit many outright belly laughs, but it functions admirably as a curio.

Finally, I got a head start on the closing night film of the Chicago International Film Festival with The Torch, a home-grown doc about one of the city’s most beloved figures, Buddy Guy. But of course, it’s not just about the 83-year-old blues legend, but about what the “last man standing” of blues’ great guitarists leaves behind for the future. Jim Farrell‘s doc posits, quite straightforwardly, that Buddy’s legacy is in his tutelage of young blues musicians (many of whom answered his open call to come up on stage and play when they were kids). It’s through that process that he found his heir apparent, 19-year-old Quinn Sullivan, when he shredded like hell at a 2007 concert and has been under Buddy’s wing ever since.

For Chicagoans and blues aficionados, The Torch offers plenty of easygoing appeal. It trains its camera on Buddy Guy, after all, a man who matches his affable wit and personality with an equally impressive number of stories, myths and tall tales about life on the road. Plus, it’s wall-to-wall with incredible blues music, all centered around Buddy’s inimitable talent on the guitar (especially his recurring gag of playing the blues while walking – or even driving – around the building with a wireless electric axe).

But Farrell can’t quite decide if The Torch is going to be a movie about Buddy or about Quinn, or even about songwriter Tom Hambridge, who helps guide Quinn through the stepping stones he needs to build his own career as a musician. To his credit, Quinn’s already a hell of a performer, fingers flying on the electric guitar and with the voice of an angel. He’s also a sweet-seeming kid, grateful for his status as Buddy’s protege and willing to learn and grow as he goes. But his story is just inherently less interesting than Buddy’s, as sweet and talented as he is; he doesn’t have the mythos and the stories of Buddy, which only accentuates the feeling of loss we’ll have once Buddy’s gone. As a doc, it thrives as a tribute to Buddy, but as a rumination on the future of blues (and the need to keep it alive), the potential energy of Quinn’s as-yet launched career isn’t enough to sustain it all the way through. (There’s also a residual strangeness to the concept of passing the blues off to a bunch of white musicians, but that’s perhaps an angle for another time.)