Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableDocs about comics legends and legendary pranksters collide with psychedelic brainworms and Blaxploitation cult classics.

(This dispatch is part of our coverage of Fantastic Fest 2022.)

Say what you will about All Jacked Up and Full of Worms, the debut feature from writer-director Alex Phillips: It does exactly what it says on the tin. The entire film is about a bunch of odd people off on a surreal drug trip fueled mainly by the ingestion of hallucinogenic worms. Those involved include Roscoe (Phillip Andre Botello), a janitor at a sleazy motel who comes across the worms left behind by a prostitute client; Benny Boom (Trevor Dawkins), a self-proofed horndog; and a perennially high couple (Carol Rhyu and Mike Lopez) on a random killing spree who seem determined to involve Roscoe and Benny in their peculiar idea of fun.

As you can probably surmise, narrative cohesiveness isn’t precisely the driving force behind this film. It’s a decidedly strange work designed to blow viewers’ minds with its bizarre storytelling. But at the same time, it wants to empty their stomachs via the often-nauseating imagery on display. I confess that I didn’t care for it that much—in obvious inspirations like David Lynch’s Eraserhead and the early films of John Waters, the weirdness and disturbing imagery felt like integral elements. The lunacies Phillips offers often feel too blatantly calculated for shock value and, even with an abbreviated running time, get pretty tiresome by the end.

It ultimately feels like the kind of thing you might come across in a less-than-desirable time slot at a decidedly average underground film festival. But in a time where seemingly every other film seems to have been designed to maximize corporate profits while exploiting core IP assets, it’s refreshing to see that something this odd could somehow beat the odds and get made. This is not for everyone, but those with a taste for the wilder corners of cinema (and a reasonably strong stomach) might get more out of it than I did.

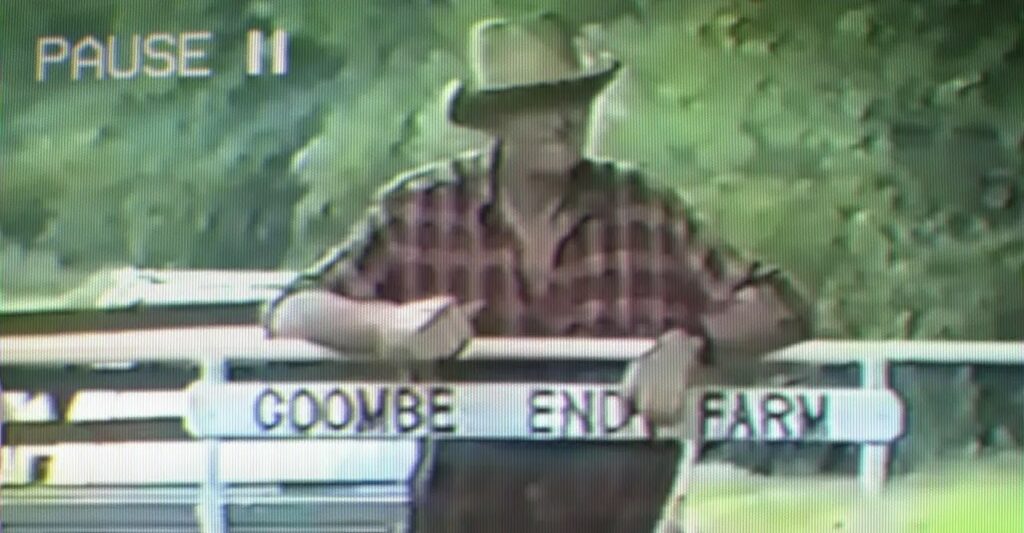

A far more jaw-dropping experience in this year’s Fantastic Fest lineup was A Life on the Farm, a short documentary from Oscar Harding whose benign title hardly begins to hint at the oddities to follow. It tells the story of Charles Carson, an offbeat British farmer who decided to stave off boredom and loneliness in his later years by buying a video camera and making a movie about his life. The results were singular, to put it mildly, with segments involving the birth of a calf, the funeral for a pet cat, and Carson taking the body of his just-deceased mother around the grounds to say a final goodbye.

When the tape wound up online, it became an immediate viral sensation. However, Harding’s film is not just a look at an oddball who made a strange video that caught on with people wondering what the hell it could be. Instead, through interviews with people who knew him and clips of Carson’s surprisingly elaborate footage, he gives us a thoughtful and ultimately moving portrayal of the healing power of artistic expression as a way to help process grief and, thanks in part to a truly unexpected twist to Carson’s story, it ends on a life-affirming note that it genuinely earns.

Two of the people interviewed in A Life on the Farm are Joe Pickett and Nick Prueher, who showed clips from Carson’s film as part of their Found Footage Festival, a traveling event comprised of clips from strange and obscure videos culled from the massive collection they have amassed over the years. Pickett and Prueher also turn up in Chop & Steele, a documentary from Ben Steinbauer and Berndt Madre that chronicles how two childhood friends built a mini-empire on something so goofy and how they stood to lose everything as a result of something even goofier.

Mostly to amuse themselves while on the road, the pair would pitch themselves to local TV stations as a variety of absurd characters—a chef who has written a book on making smoothies out of Thanksgiving leftovers or a bodybuilding duo that doesn’t appear to have hit the gym since it was compulsory in high school—and would more often than not get invited on, playing things out to lunatic extremes. At the same time, the newspeople act as if everything is normal. Alas, the parent company for one station is not so amused and sues the duo, instigating a protracted legal dispute that threatens their very livelihood.

Meanwhile, the producers of America’s Got Talent get wind of them and invite them on the show, leading the two to try to come up with a way of doing the show without their anarchistic spirit being co-opted by mainstream corporate media. (Without giving it away, I will merely say, “Mission accomplished.”)

Featuring interviews with subjects ranging from fans like Bobcat Goldthwait and David Cross to their parents and Pickett’s extremely tolerant wife, the film is a slight but undeniably charming hymn to the joys of cheerful prankishness. It’ll delight their fans, intrigue newcomers, and possibly leave viewers with a much higher opinion of Howie Mandel than they may have had going in.

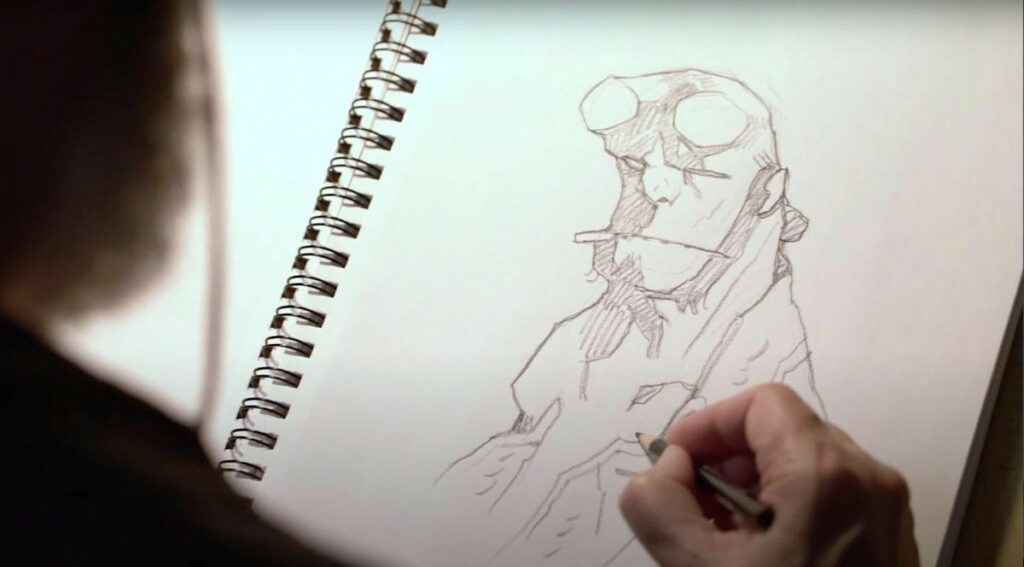

Mike Mignola: Drawing Monsters (Fantastic Fest 2022)

Another documentary, Jim Demonakos and Kevin Konrad Hanna’s Mike Mignola: Drawing Monsters, is a more straightforward affair that looks at the life and work of the celebrated comic book artist most famous for creating the cult favorite Hellboy. Through interviews with family, fans, and colleagues, we chart his growth from a young kid who grew up mad for comic books and movies to his early career serving as an inker for hire with established comic book studios, which eventually inspired him t take the chance to set off on his own. This decision would eventually lead to the creation of Hellboy, which started slow but would eventually spawn several related titles that would make up the so-called Mignolaverse and lead to him becoming regarded as one of the leading comic book creators of our time.

It doesn’t simply take Mignola’s accomplishments as a given. It makes an effort to illustrate the aspects of his craft—particularly in his use of minimalism and expressionist design—and how they make his work particularly distinctive. It also does an excellent job of negotiating his sometimes conflicted feelings towards the two Hellboy films made by Guillermo del Toro; he generally likes the films and appreciates how they vastly expanded his audience, but admits to some tensions with del Toro regarding certain aspects he didn’t agree with. Although hardly groundbreaking, Drawing Monsters is a thoughtful and entertaining celebration of an undeniably unique artist whose work should interest both hardcore fans and newbies alike.

Another fascinating piece of pop culture anthropology was on display in Solomon King, a 1974 Blaxploitation film that was thought to be lost. That is, until Deaf Crocodile Films, working from the only known complete print stored at the UCLA Film & TV Archive, undertook a complete 4K restoration. It was the brainchild of Sal Watts, a one-man band who co-directed, wrote, produced, and even supplied the men’s outfits from a chain of clothing stores he owned.

The film starts in the Middle East when an attempted coup by the duplicitous Prince Hassan (Richard Scarso) causes oil field overseer Manny King (James Watts) to spirit the now-endangered Princess Oneeba (Claudia Russo) out of the country to Oakland. There, she can be appropriately protected by the only man capable of such a task: His brother Solomon (Watts). Solomon has a resume that even Buckaroo Banzai might envy—wealthy businessman, former CIA agent, and Special Forces operative, not to mention catnip to the ladies. He winds up drawing on all those talents when Hassan’s operatives track him and the princess down.

By most critical standards, Solomon King is a mess. The story is primarily constructed from bits and pieces of films that popped up earlier in the Blaxploitation cycle. The undeniably ambitious scope of the screenplay is frequently undermined by the lack of an adequate budget (such as a shot of a couple of dinky little oil wells meant to represent the vast Saudi oil fields). The cast comprises non-professional actors who are more concerned with remembering their lines than investing them with any real emotion.

And yet, while the film is not necessarily “good” in the classical sense, it’s undeniably fascinating to watch. Watts and co-director Jack Bomay shot most of the scenes in real locations they could presumably access on the cheap. Because of that, the resulting film takes on a documentary-like feel that makes for an interesting juxtaposition with all the loopy action going on. In front of the camera, Watts may not be the most outstanding actor, but he demonstrates enough charisma to make one wonder what he could have accomplished if he had been working with stronger material.

Fast-moving, reasonably exciting, and driven by a legitimately impressive funk score, Solomon King is a fun blast of retro nonsense that should appeal to genre fans and make one wonder what other long-forgotten gems are languishing in vaults awaiting rediscovery.