Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableEvery month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. 40 years after Camp Crystal Lake appeared on the silver screen, we look back at Friday the 13th and how the perennial slasher series mutated across the years. Read the rest of our Friday coverage here.

The Friday the 13th series has never exactly been known for their inspiration or creativity. Even the 1980 original was little more than a blatant Halloween knockoff distinguished only by its vastly increased and startlingly grisly body count. As the saga ground on throughout the decades, the makers came up with an array of gimmicks to breathe life into them. Some were mildly inspired (the effective 3-D presentation of Part 3 (1982) and the self-aware humor of Jason Lives (1986)) and some less so (pitting Jason against a Carrie clone in The New Blood (1988)).

The slasher movie genre had been reduced to little more than unnecessary sequels to tired franchises. But in 1989, the producers came up with a gimmick that actually aroused genuine interest among genre fans — let Jason loose in the Big Apple!

Friday the 13th: Jason Takes Manhattan is a film whose central appeal is summarized so succinctly in its title. But its execution is so thoroughly botched that they managed to do the one thing so many people tried and failed to do the decade prior: bring the series to an ignominious (though temporary) end.

The idea was suggested by writer-director Rob Hedden, making his feature debut on the basis of his work on an episode of the then-current Friday the 13th television series. Hedden strove to find a new venue in which to present Jason’s mayhem instead of another trip to the same woods people seem inexplicably eager to return to, despite all those pesky bloody murders over the years. In one of his ideas, Jason would make his way onto a cruise ship and pick off passengers while hiding out below deck. In the other, Jason would turn up in New York City and do his thing in a variety of familiar places ranging from Times Square to Madison Square Garden to the Statue of Liberty.

The producers liked both concepts, so Hedden devised a plot in which a group of recent graduates from Crystal Lake High would take a cruise from there to New York with a newly revived (don’t ask) Jason murdering them both at sea and in the Big Apple.

While the finished film is one of the dumbest in a franchise that, even at its best, has never been famous for firing on all cylinders, the notion of Jason laying siege to Manhattan is an inspired one. The possibilities boggle the mind — slicing up drugged-out Yuppies waiting to get into some trendy nightspot; getting caught in the middle of one of those spontaneous street dances performed by those kids from Fame and hacking his way out; stumbling across a sleazy real-estate developer with shaky finances and dubious hair and reducing him to something resembling grape jelly.

Unfortunately, while the franchise was still profitable for Paramount Pictures, the grosses had been steadily slipping. The only way to keep making money off of them was to keep the budgets low. Shooting primarily on location in the biggest city of the world would have been prohibitively expensive. While this film would prove to have the highest budget of any entry in the series to date (roughly $5 million), that would not begin to cover the costs.

As a result, several decisions were made that would lead to the film’s eventual downfall. The chief one was to rejigger the screenplay so that the first two-thirds of the action would take place on the ship, Jason and company making an abbreviated appearance in Manhattan for the third act. Then, most of the film (including many of the scenes purportedly set in New York) wound up being filmed in Vancouver, British Columbia.

In fact, the production ended up actually spending only a couple of days on location in New York, most notably in Times Square, in what would prove to be the most notable sequence. Alas, Vancouver’s performance as New York was not particularly convincing, and the substitution became even more glaring whenever there was a brief glimpse of the real thing.

They managed to do the one thing so many people tried and failed to do the decade prior: bring the series to an ignominious (though temporary) end.

Many have joked that the resulting film should have been subtitled Jason Takes A Cruise instead of Jason Takes Manhattan. It might have actually done better, at least with the fan base, if it had. The problem is that Paramount decided to lean hard on the New York angle as a way of promoting it. They even produced a poster of Jason slashing through the then-ubiquitous “I Love New York” logo (until they were busted for unauthorized use and forced to replace it).

That concept inspired genuine excitement and curiosity among genre buffs—who now largely went to Friday the 13th movies out of a sense of obligation, if at all—and that lasted right up until the film premiered and they discovered what was really going on. Even in those pre-social media days, word of mouth traveled pretty fast. While it beat Freddy Kruger into theaters, it ultimately proved to be the lowest-grossing film of the entire series. (Ironically, Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child proved to be a flop as well—apparently in the summer of Batman, there was no interest in the slasher icons.)

Even though there have been worse Friday the 13th films over the years, Jason Takes Manhattan isn’t exactly begging for rediscovery. Hedden’s direction is reasonably stylish on a purely technical level, but he never generates any discernible trace of suspense at any point. With a couple of exceptions (including a bit in which Jason literally knocks a guy’s head off his shoulders with a single punch), the kills aren’t especially memorable either.

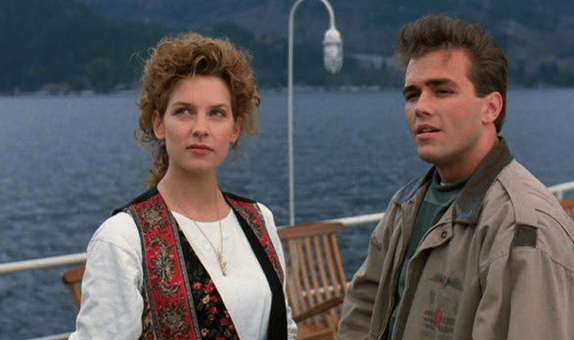

The characters are the usual array of cliches. There’s the Final Girl (Jensen Daggett, in a role that she reportedly won over the likes of Pamela Anderson and Elizabeth Berkley); the Blandly Handsome Guy (Scott Reeves); the Jagoff Adult (Peter Mark Richman); the Creepy Red Herring (Alex Diakun); the Bad Girls (Sharlene Martin and Kelly Hu); the Nerd (Martin Cummins) and the Black Guy (V.C. Dupree). By default, Jason (Kane Hodder, in his second outing behind the mask) serving as the only memorable one of the bunch.

Things start to perk up a little bit once the film reaches Manhattan. There are moments that work: Jason’s encounter with a boombox, jaded Manhattanites regarding him as just another weirdo on the streets. But they’re outstripped by the film’s budgetary compromises and an inexplicable unwillingness to fully exploit the satirical potential of its concept. Even Friday the 13th: Jason Lives a couple of years earlier managed to capitalize on its premise more effectively.

Ultimately, Friday the 13th: Jason Takes Manhattan is more wearying than anything else. It made viewers wait an unconscionably long time to get to the heart of its premise, and when it finally did, it didn’t come close to living up to it.

Following the failure of this film and the cancellation of the TV series, Paramount eventually sold the rights to New Line Cinema. It would be more than four years until the franchise would return to multiplexes. It may not have been consciously planned to end the franchise, but it does convey the feeling of a series that has gone on long past its shelf life and is running on fumes.

The big finale, in which Jason is drowned in a flood of toxic waste (you almost want to hear Jason scream “Ach, the hockey mask does nothing!”), has a pro forma feel to it that suggests both a lack of inspiration and a determination to finally get rid of the character once and for all. After all, what else could they do with him? Send him to Hell? Send him to space? Send him to wherever Freddy Krueger is hanging out? Send him to Michael Bay’s house? Don’t be ridiculous.

Oh well, at least it’s better than A New Beginning. Now that movie really sucks.