Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableHow Francis Ford Coppola’s visually-stunning romance set out to change studio filmmaking forever — and crashed and burned along the way.

By the end of the 1970s, Francis Ford Coppola was on top of the world. He’d just come off a string of films that weren’t just critical and commercial successes, but masterpieces that defined cinema as an artform: The Conversation, Godfathers I & II, and Apocalypse Now — the kind of run that basically guarantees you carte blanche to do whatever the hell you want. With that kind of blank check, Coppola didn’t just set out to make an intensely personal swing for the fences: with Zoetrope Studios, and One from the Heart, he sought to revolutionize the way movies were made and carve out a space for auteurs to make intensely personal projects that didn’t require four-quadrant appeal.

Unfortunately, that same commitment to single-minded auteurism would be his, and Zoetrope’s undoing.

It’s almost impossible to view One from the Heart outside its cultural and historical context: a gargantuan gamble by an unstoppable auteur, one which tests the limits of studio largesse and the patience of audiences who aren’t on the artist’s incredibly specific wavelength. Starting out as a modest $15 million romantic comedy written by Armyan Bernstein for MGM, Coppola ported it over to his own fledgling studio, Zoetrope for the production side, self-financing the entire effort and bumping the budget to $23 million.

Zoetrope was pitched as an artist’s paradise, an alternative to the stifling studio system of Hollywood where avant-garde filmmakers could ply their craft, and working artists could enjoy resources, fair pay, and equitable work weeks. If it (and One from the Heart) had worked, we could have seen a renaissance of ethical, equitable independent filmmaking to rival the blockbuster model of Tinseltown. (Oh, how we hoped.)

Along with the budget, the scope of the film expanded: with Coppola rewriting the script with Bernstein, One from the Heart‘s margins expanded to become a glitzy, neon-soaked ode to the golden age of Hollywood musicals, while still attempting to hold onto the gritty realism and moral complications of 1970s Hollywood cinema. Apocalypse Now cinematographer Vittorio Storaro came on board, along with Tom Waits, who’d write the mournful ballads that would serve as the faux-musical backdrop for the story (with vocals by Waits and Crystal Gale). Rather than film it like a kitchen-sink drama, Storaro and Coppola make unabashed use of Zoetrope’s lavish soundstages, detailed miniatures, and sumptuous backdrops, every set, and frame bursting with color, leaning into its artifice in form if not in content.

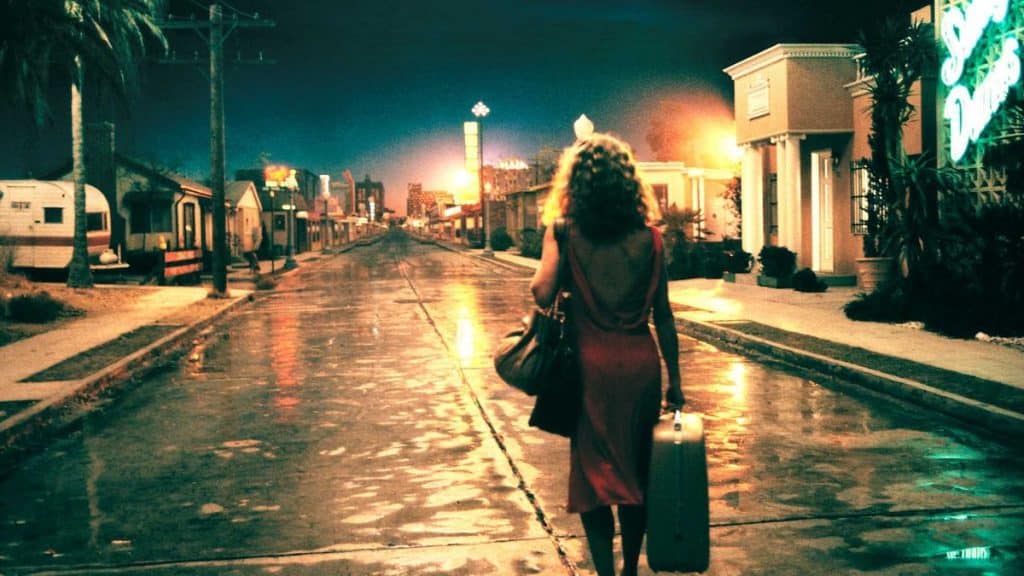

And it’s the content that proves One from the Heart‘s biggest hurdle for a viewer: What price Storaro? Are all the picturesque, painterly images worth it if they’re centered around such a limp, unaffecting romance? The premise, such as it is, concerns a workaday couple living in Las Vegas during an overnight spat: there’s Hank, played with fussy stubbornness by Frederic Forrest, whose practicality and lack of imagination stifles the dreams of travel agent Frannie (a luminous Teri Garr), who walks out on him after their fifth anniversary makes them both suspect they’re wrong for each other.

Both break out on their own to escape the doldrums of their domesticity, finding refuge in the comforting words of their friends (for Hank, it’s Harry Dean Stanton; for Frannie, Lainie Kazan) and striking up flings with more exciting romantic alternatives — respectively, Nastassja Kinski‘s exotic circus performer Leila and Raul Julia‘s seductive waiter-cum-crooner Ray.

Conceptually, there’s something remarkable in the dissonance between the glamour of their Vegas surroundings and the humdrum desperation of their ordinariness; Storaro’s theatrical cinematography (shot in Academy ratio, of course) makes every shot look like either Norman Rockwell or Salvador Dali, depending on where you’re looking, offering a neon-soaked theatricality to spice up the average joes we’re following. To her credit, Garr understands the assignment, being glamourous without being unattainable, her vibrance (and physicality, as her iconic dance scene with Julia belies) evoking Shirley MacLaine at her height.

Honestly, the problem’s probably more with Forrest, or more specifically, Hank — who’s by definition the kind of boring, middle-aged white guy Frannie doesn’t find appealing anymore. He’s the one least enamored of the fantasy of the American Dream (“America, it’s phony bullshit… nothing’s real! It’s all tinsel!”), but he fails to offer a suitable alternative, both for Frannie and for the audience. When the rest of the film is screaming at us to dream big and see the bright colors on which life is painted, what fun is it to stick around such a mope, one who only sees what he’s got after he gets to have a fling with Nastassja Kinski as the Nevada sun rises?

It’s an ode to saturated, hyper-real MGM musicals that shies away from actually having its characters burst into song. Waits’ gravelly voice merely approximates Hank’s cynical gruffness in the background; there’s no need for Forrest to join the chorus. It’s a fantastical anti-musical committed almost entirely to stunning the senses, each new scenario drawing you back into the artifice before harshly reminding you that real life, real relationships, don’t really work out like that. Both Kinski and Julia are specters, romanticized versions of the storybook romances instilled in us to desire by the very films One from the Heart emulates. Hank lambasts the tinsel and phony bullshit, but that’s the very thing Coppola privileges in his film. That can make it hard to glom onto.

And yet, despite the drabness and confusion of its premise, One from the Heart is impossible to look away from. I may not care whether Hank and Frannie get back together at the end (they do, in a move as magical as it is deeply contrived), but I do care about how it feels to see Kinski kicking her legs up inside a life-size martini glass, or looking down at Hank with all the larger-than-life desire of that infamous shot of Joi from Blade Runner 2049.

One from the Heart

Blade Runner 2049

Frannie doesn’t need to actually go to Bora Bora to experience the fire of a sultry tango with Raul Julia, drenched in honeyed lighting during the closest thing the film has to an actual musical sequence. It’s these singular images, and the aching sincerity in which Coppola presents them to us, that make One from the Heart the kind of orphaned artwork I can’t help but root for.

Naturally, the film was a disaster: it got poor reviews and made less than a million dollars at the box office upon release. Audiences ran from it like it had bought them a deed for a fixer-upper home on their fifth anniversary, and Zoetrope Studios suffered mightily as a result. Coppola would have to dial back his ambitions and take on more modest, marketable works like The Outsiders, and he’d never regain that sense of cultural supremacy. (There’s a reason most of his money comes from wine now.)

As is, One from the Heart functions best as art installation rather than cinema, a series of god-tier images and sequences underpinning a story and characters we don’t care about very much. But even as our Icarus flies too precariously towards the sun, we can appreciate the gumption and the majesty of that ambitious flight — even if we know what happens afterwards.