Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableEvery month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema, and the filmmaker’s own biography. October sees not only the onset of Halloween but the birthday of cult horror maestro-turned-mainstream filmmaker Sam Raimi; all month, we’re web-slinging through his vibrant, diverse filmography. Read the rest of our coverage here.

Come back with me to a simpler time. A time when superheroes didn’t completely dominate the box office and Hollywood didn’t think they weren’t box office poison. And just because said superhero movie was made by Marvel didn’t mean they were part of a larger cinematic universe.

As a matter of fact, the Marvel Cinematic Universe was just Marvel, and in 2002, their movies were mostly self-contained stories. Blade kicked things off in 1998, followed by the first X-Men movie in 2000, then Blade II in 2002 — hardly a forebear for the bright, optimistic, and mostly bloodless tone the MCU carved out for itself.

Audiences were already hungry for something else though, even if the industry was slow to catch on, with Iron Man years away from kicking off what became known as the MCU in 2008. At the time, Americans were still reeling from 9/11, hungry for a more earnest hero they could root for. We needed someone with no complications, one who was clearly on the side of good and proudly declared it.

And just as the people were ready for a change, along came a spider…man. Cheesy? Absolutely, and Sam Raimi’s 2002 Spider-Man movie, with Tobey Maguire as the beloved webslinger, doesn’t try to be anything else. It embraces the hero’s earnestness, staying true to the source material while introducing him to a whole new generation. The result was a massive critical and commercial success, with the movie setting box office records and proving that nerd culture could not only be mainstream, but profitable.

If Spider-Man proved all that, it’s partly because it’s deeply aware of how nerd used to be a label to be avoided at all costs. The bullies may be one-dimensional cartoons, but you feel for Peter Parker far before he ever gets bitten by a radioactive…I mean, genetically altered spider, since his high school days mostly involve him being forced to run after his school bus, and thinking his crush Mary Jane (Kirsten Dunst) is noticing him, only to be painfully reminded of his invisibility.

Raimi is a nerd who made good before it was cool — perhaps Raimi’s knowledge of high school tribulations is why Peter only spends half the film there, and why he and Maguire worked so well together. Successful actors tend to be a notoriously photogenic bunch, and it’s hard to picture anyone but Maguire being able to sell the movie’s brand of earnest awkwardness.

People usually reserve credit for Spider-Man‘s cheesy sincerity for the bright tone and early CG effects, which were still relatively new. By comparison, much of the effects look silly today. But the awe many New Yorkers felt as Spider-Man swung his way through their city echoed the reaction of many moviegoers.

Peter himself may feel like a throwback that makes Captain America look edgy by comparison, but he’s the kind of nice guy who is refreshingly non-creepy, even now. He doesn’t follow his lifelong love Mary Jane around to her work or her home. Most importantly, he asks permission before he takes her photo, an act of consent even for modern love interests.

That brings us to one of the movie’s biggest problems, or as I like to call it, The Problem That Shouldn’t Be A Problem At All: Mary Jane. That the character doesn’t work isn’t the fault of Dunst, who revealed herself to be one of the most talented actresses of her generation in her breakout role in Interview with the Vampire at age 11, which saw her holding her own against two of cinema’s most charismatic leading men.

Dunst doesn’t fare as badly here as she would in the sequels, which more often than not doubled down on its flaws regarding her character. There’s no doubt that Mary Jane has depth and ambitions of her own. The movie doesn’t feel the need to punish her for dating Peter’s bully Flash Thompson (played by a very young Joe Manganiello).

Peter using his powers to enact physical violence against his tormentors, tellingly, doesn’t endear him to her. Instead, it’s Peter’s kindness, and above all, his respect for her that ultimately wins Mary Jane over. His decision to continually support her, whether it’s her dream of becoming an actress, or reassure her about her humiliating waitressing job, even as she’s dating his best friend Harry (James Franco), is refreshing.

Part of their closeness is incidental. Mary Jane is literally the girl next door, so the movie can dispense with the disturbingly resilient trope that has men continually stalk their love interests. His continued presence in her life after they graduate is partially due to her relationship with Harry and Peter’s loving Aunt May (Rosemary Harris), who has become a kind of surrogate mother to Mary Jane.

It embraces the hero’s earnestness, staying true to the source material while introducing him to a whole new generation.

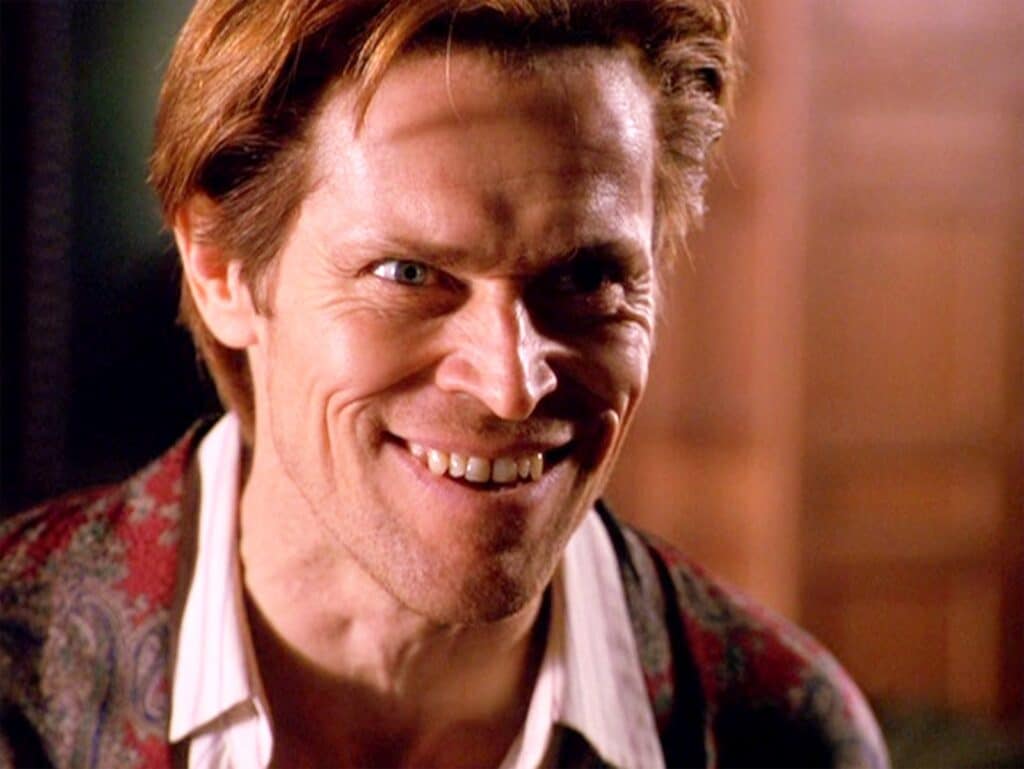

The problem isn’t that Mary Jane lacks depth; it’s that the movie lacks interest in her unless she’s a love interest for whatever age-appropriate male character she happens to be around. As such, her main role is to be rescued. It’s up to us to piece together her character from the scraps Raimi and screenwriters David Koepp and Scott Rosenberg give us. They reserve real depth for the men, from the doomed but warmly memorable Uncle Ben (Cliff Robertson) to Harry and his father Norman Osborn, a role so perfectly suited to Willem Dafoe’s talents that the character’s death would continue to play a major factor in both of the sequels.

Some of it is just luck. Norman Osborn may be a villainous CEO, but 2002 was probably the last time such a role could have a tragic dimension. Norman’s evil alter ego may not get the greatest costume, but he does get the best lines, and we feel for the man from whence he accidentally sprung. Norman isn’t a sinister figure pulling the strings from the shadows, he’s a scientist first and foremost who’s deeply invested not just in Oscorp, the company he founded, but in unleashing human potential. His decision to test the formula on himself rather than a volunteer is what turns him into the insane Green Goblin.

It makes him startlingly sympathetic, even as he emotionally neglects his son for the more scientifically and technologically savvy Peter, who also sees him as a kind of surrogate father. When Norman becomes evil, he also transforms into a fallen patriarch, attempting to persuade Peter to use his abilities for selfish ends. When Peter rejects his offer, he lashes out in the most toxic of ways, attempting to kill not just Mary Jane but Aunt May.

The climax at the bridge is the corniest moment in a film full of them and goddamn it, it works. The hero not only has to make a choice between saving a group of innocent children or the woman he loves, he gets help from a group of New Yorkers. It’s a show of unity that resonated for a city still coming to grips with the 9/11 attacks.

Later films wouldn’t try to replicate this success so much as build on it. Spider-Man himself would undergo a radical change, from the nerdy outcast who had to worry about paying his rent to a guy who had access to high-tech killing machines thanks to his friendship with billionaire Tony Stark. Marvel left working-class relatability to other, no less compelling versions of Spider-Man, such as Miles Morales in Into the Spider-Verse.

Superhero movies have gotten both bigger and smaller since Sam Raimi’s version of the character first hit theaters. But it’s hard to imagine them without the humor and heart they’ve come to embrace if Spider-Man hadn’t swung into theaters — a move which set much of the style and tone for what came after.