Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableStallone’s ludicrous tough guy cop picture is the most ludicrous tough guy cop picture.

Film Comment used to run a semi-regular feature entitled “Guilty Pleasures” in which they would invite someone to write a piece about films that have often been ignored or reviled by critics and the public but for which they still maintain a deep love for any number of reasons. These articles were always fun to read but I must confess that the notion of a so-called “guilty pleasure” is one to which I have never quite subscribed. My feeling is that if a movie gives you some form of pleasure—either because it is genuinely good or because of its camp value—you should be able to celebrate it without feeling any guilt over whether or not it conforms to general standards of artistic acceptability.

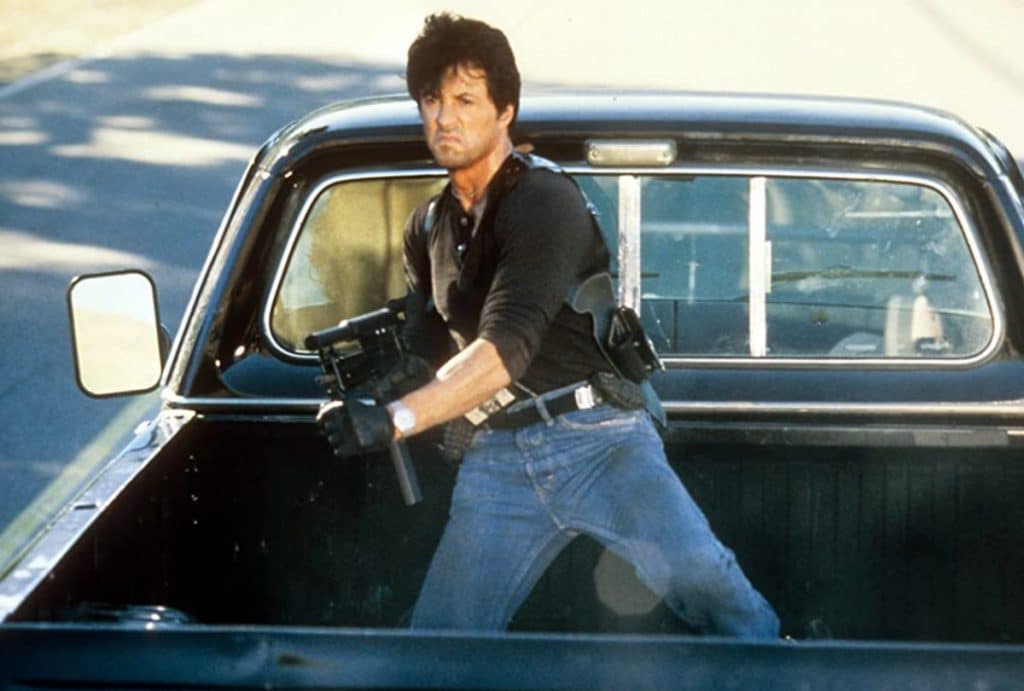

That said, if I were ever commissioned to make a list of guilty pleasures and concentrate solely on films that I have a fondness for despite realizing that they are, indeed, pretty awful by most applicable critical standards, I have a feeling that the super-violent Sylvester Stallone action epic Cobra (1986) would rank pretty close to the top. Even when it first came out 35 years ago, it was largely dismissed as a sloppy, undisciplined testosterone fest. One that had nothing more on its mind than appealing to the basest instincts of its target audience of action movie freaks and went about accomplishing that in the most Neanderthal manner imaginable. Watching it today is a jolting experience as well—it seems impossible to believe that something as crudely made and casually cruel as this could have possibly been deemed worthy of a commercial theatrical release. Put it this way—it was co-produced by Cannon Films, who specialized at the time in insane action films ranging from Ninja III: The Domination (1984) to the Death Wish sequels, and even by their standards, it comes across as a bit much.

I agree with all of the sentiments I have cited in the previous paragraph—Cobra is stupid, poorly made and unnecessarily savage even in comparison to the stupid, poorly made and unnecessarily savage action movies of the time when it was made. And yet, even though I recognize all of its flaws, I nevertheless have a fondness for the film that I cannot deny nor shake. It is not nearly the best of the quasi-fascist 80s-era action epics in which monosyllabic macho men went about extracting brutal justice upon people so vile that even Sister Helen Prejean would find herself cheering their executions. However, it may be the most of such films, a work that takes the cliches and tropes of the genre and plays them out on such a large scale and with seemingly no sense of humor or irony regarding its excesses that it ends up playing like an exceptionally straight-faced parody of itself. Whenever someone does a spoof of such films, this is the one that they are using, consciously or not, as their template.

At the time that the film was being made, Stallone was riding high on the twin successes of Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) and Rocky IV (1985), which helped erase memories of several recent bombs and put him in the position of doing virtually anything he wanted. A few years earlier, the story goes, he had signed on to star in a project called Beverly Hills Cop and was allowed to rewrite the screenplay. His version eliminated most of the comedy and replaced it with violent action. When he turned in this draft, the studio rejected it and the two came to a parting of the ways. Not one to let genius be set aside, Stallone use his clout to do a new project that would allow him to utilize those ideas in a new screenplay, one ostensibly inspired by the Paula Gosling novel Fair Game, that would presumably give him a third tough guy film franchise.

As the story begins, Los Angeles is under siege from a series of violent and seemingly unmotivated attacks, including a siege at a grocery store that is eventually resolved when maverick cop Marion “Cobra” Cobretti (Stallone) arrives on the scene to blow the perpetrator away. Cobretti is convinced that these crimes are somehow related but his smarmy superior (Andrew Robinson) pooh-poohs his suspicions and derides his methods whenever he gets a chance. Surprise—Cobretti is right and the crimes are being committed by a murderous cult led by a guy who calls himself The Night Slasher (Brian Thompson). The Night Slasher is a murderous creep prone to prattling on about killing the weak in order to create a stronger world populated with people like his theoretically stronger and smarter allies.

Well, they aren’t that smart evidently because while a few members are carrying out another kill, they are witnessed by glamorous fashion model Ingrid Knutsen (Brigitte Nielsen, who also happened to be Mrs. Stallone at the time) and while they manage to track her down and kill her lecherous photographer (David Rasche, who would soon do his own spoof of films like this with the cult television series Sledge Hammer!), she manages to escape and get to the cops. After another unsuccessful attempt on her life confirms Cobra’s suspicions that it is all the work of a violent mob, he and his partner, Sgt. Tony Gonzalez (Reni Santoni) are charged with protecting her and they decide to spirit her out of the city. However, thanks to the machinations of another cop (Lee Garlington) who is also a member of the cult, they are tracked down, leading to a series of chases and shootouts that climaxes with a final battle between Cobra and the Night Slasher in a steel mill and you probably don’t need to be a homicidal genius to guess how it turns out.

One does not have to watch Cobra for too long to realize that the whole thing is basically an attempt to give Stallone a Dirty Harry-style film franchise. Hell, it even goes so far as to cast two of the actors from that film, Santoni and Robinson, in key roles here—Santoni plays pretty much the same part as he did fifteen years earlier in the original 1971 film while Robinson, who was the psycho killer in that one, now plays a top cop who doesn’t like Cobra’s violent method. (Supposedly Stallone’s original script had this character turn out to be the actual leader of the cult, a twist lifted directly from the sequel Magnum Force (1973).) That film, as those with longer memories will recall, was dismissed by many critics as being both cartoonishly excessive and borderline fascist in its attitudes. However, the original Dirty Harry was not quite the lunkheaded exercise in savagery suggested by its critics—it told a story that was smarter and more conflicted than that (which was not the case with the sequels) and contained a performance by Eastwood that is actually a lot more droll than expected—as with his spaghetti Westerns with Sergio Leone, he recognizes the silliness of the material and plays to it without ever breaking character by giving the audience a wink to let them in on the joke.

It (Cobra) is such an exercise in pure unchecked and misplaced testosterone run amuck… that it exerts strange but undeniable fascination.

Cobra, on the other hand, seems t be going out of its way to come across like the version of Dirty Harry that was perceived by its critics. It is staggeringly violent throughout and the attitude that it espouses about how violence is the only solution to life’s problems is kind of creepy and while I would hesitate to flat-out call it fascist in tone, it comes extraordinarily close to accomplishing that. There is also a noticeable lack of anything resembling a sense of humor to the proceedings—everything is presented with a deadly serious attitude that inevitably comes across as unintentionally hilarious, especially as the action grows increasingly overblown. From a technical standpoint, the film is also pretty lousy as whoever directed it (although George Pan Cosmatos is credited as director, it has been reported that Stallone did much of the actual direction) seems to have approached the editing in the same way that the Night Slasher approached his victims—hacking away until what is left is barely recognizable.

As for Stallone, while he can be an undeniably engaging performer when he wants to be, he is so brutishly impassive as he fires off both bullets and his would-be tough guy bon mots (including the infamous “You’re a diseased, and I’m the cure”) that he inspires more revulsion in viewers than anything else. Yes, the film does try to humanize Cobretti by creating the beginnings of a relationship between him and Ingrid but this ends up being underdone by the lack of any discernible chemistry between the Stallones—Stallone seems completely disinterested (possibly because he knows that he already has the bigger chest between them) and while Nielsen may have been staggeringly beautiful, to say that she could not act work a lick would be an insult to licks.

And yet, despite its rank stupidity, technical crudeness (the film reportedly underwent a last-minute recut in order to avoid a “X” rating and to reduce the runtime in order to squeeze in extra shows and does it ever show) and its weirdly aggressive tone (it feels at times like the first movie affected by roid rage), Cobra still manages to exude a strange fascination that cannot be denied. It is such an exercise in pure unchecked and misplaced testosterone run amuck—one that never makes an attempt to appeal to anyone outside of its target audience of 15-year-old boys (literal and metaphorical) seething with bloodlust—that it exerts strange but undeniable fascination. One doesn’t so much watch it as study it in the way one might observe a lab experiment that has gone wildly out of control—it doesn’t work in any of the ways one might expect but you cannot take your eyes off of it as it flies further off the rails into complete lunacy.

The punchline to the whole thing is that while Cobra had a huge opening weekend, it proved to be too much of a good thing, for lack of a better phrase, for its target audience and was not the huge hit that it was expected to become. Needless to say, the would-be franchise did not continue on—the Stallone-Nielsen union would not last much longer either—though it would go on to become a campy cult item whose dramatic excesses now inspire only laughter instead of a desire to see bad guys get their just desserts. In the end, Cobra is a film that takes a typically overstuffed action extravaganza of the time, cuts everything outside of the violence down to the bone and then proceeds to hit viewers over their heads with those bones for 90 unrelenting minutes.

Fun Fact: Remember how I mentioned how Cobra was based, however tenuously, on a book entitled Fair Game? About a decade later, it served as the inspiration for a second screen adaptation, Fair Game (1995), another ludicrous action exercise that marked both the beginning and ending of supermodel Cindy Crawford’s career as a thespian. Come to think of it, I have a slightly perverse fondness for that movie as well, but we will have to put off my defense of that one for another time.