Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without Cable(This piece is part of our coverage of the 2022 Sundance Film Festival.)

The nature of documentary, of course, is that the image is based in reality. But it has come to be axiomatic that reality in nonfiction film is quite complicated, that the camera changes things, truth is a moving target, etc. The exploration of these complications often makes for the most exciting films.

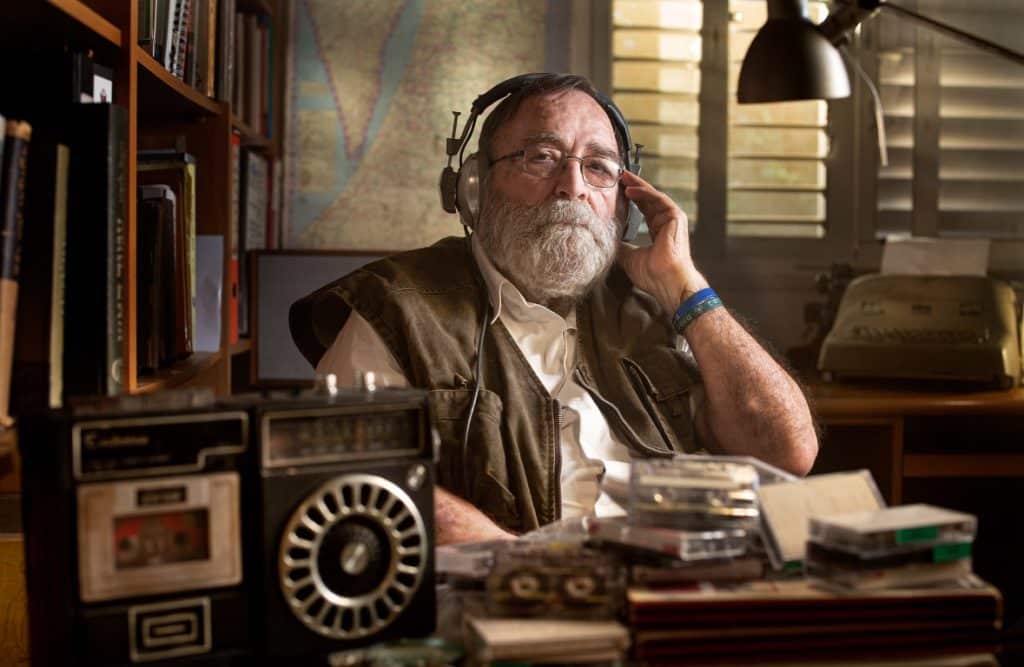

Robert Greene

I wish like hell I could remember who first said that when you’re watching nude scenes in movies, they stop being fiction and become documentary. I welcome the correct answer if you meet me somewhere. It’s a thought I can’t shake, years into my career watching films and seeing non-fiction devolve publicly into awards-bait offal and fiction look to documentary for the crassest approval. This month saw the release of Pam & Tommy, a series based on the sexual exploits of Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee, and apparently, no one thought to reach out to Pam to see if she was cool with the idea of their lives becoming fodder for bargain-basement docudrama. Why should they? The sex tape was documentary, wasn’t it? Thus important, thus fair game?

This is the stupid world we inhabit. Anything recorded once can be faked ad nauseam until “the culture” is done with it. No story is so insipid and dull that it can’t be reproduced with Oscar winners (WeCrashed coming to Apple TV+ just as soon as they figure out how to make it look like Jared Leto was on set). I thought about that quote I can’t place watching April Maxey’s Work and Prayers for Sweet Waters by Elijah Ndoumbe back to back. They both tell the stories of sex workers, one is fiction, the other isn’t, but they meet each other at the moment where bodies are on display. An audience is just one more paying customer. Both films understand that when you’re sitting in front of bodies doing what bodies can do, the distance between you and the object is non-existent, try as we might to be objective. Both are excellent. I wish more documentaries understood this. Touched the distance, played with it, understood that we understand it.

Frozen out of Sundance’s fiction program, I had to settle for shorts and non-fiction (sounds like I got the better bargain than a lot of my colleagues who had to have opinions about a movie called Cha Cha Real Smooth, which I’m sure I’ll watch in hospice when I no longer remember what a remote control does). Thankfully the non-fiction program at least had high highs.

In the shorts section, there were the earnest likes of ᎤᏕᏲᏅ (What They’ve Been Taught), about the ritual of giving back to the land at least as much as you take from it. “We’re here as guests. To be able to walk…Is a gift,” says a native elder over footage of a chainsaw obliterating a tree. Maybe too much and not enough but it’s bold. The best (doc) work done at every Sundance is by non-white Americans. Americans lost their imagination and their sense of humour. No one else has that problem. We also are apparently the biggest marks in the world. Who else would sit still for Instant Life, three-plus hours about the Sea Monkey saga, when the logline is better than any film about them could ever be? To wit, the founder of a popular children’s toy that was really just rapidly multiplying parasitic shrimp gave all his money to the Nazi party. His widow Yolanda Signorelli, a one-time porn actress from the days of roughies and nudie cuties, now has to settle some lawsuits to maintain control of the brand.

Whatever you just pictured is better than what Mark Becker and Aaron Shock come up with. That’s not true; there is one good moment that gets at the heart of things. A neighbor, a recovering addict, tasked with cleaning up the space once occupied by sea monkey breeding tanks, is in the old empty space in the dead of night when he stumbles across dirty Polaroids of Signorelli. That’s worth the price of admission. That’s what a second-person perspective doc should be.

The short-form documentaries were bountiful. Listen to the Beat of Our Images by Audrey and Maxime Jean-Baptiste is a perfect little essay on the impossibility of erasing colonialism from a map (”This place I used to hunt with my grandfather, this forest, this infinite darkness. Now it’s an image. just an image. Nothing but an image. As if it never actually existed.”). Gabriel Herrera Torres’s Motorcyclist’s Happiness Won’t Fit Into His Suit isn’t exactly a documentary, but its images of a proud hot rodder astride his steel steed can’t be a lie. That you feel in your bones. ᎤᏕᏲᏅ and Long Line of Ladies (about the preparations for ihuk, a Karuk coming of age ceremony), share a broadly palatable shape but teach us things hidden from regular programming, festival or otherwise. I find myself enormously moved by the father who says his daughter doesn’t feel any shame about calling to say her first period has come. Most white fathers look at him like he was beamed in from Olympus. How far America has fallen.

We run into trouble at the longer form. The marvelous Riotsville, USA makes Netflix’s petite The Martha Mitchell Effect look like the puff piece it is, in which the crimes of the Nixon administration are softened to fit a too-contemporary girl-bossification of mental illness, blind faith in one’s spouse, and alcoholism.

Finnish documentary The Mission, about Mormon’s terrorizing a foreign country doesn’t do nearly enough to question the safe underpinning of belief (in what?). TikTok, Boom. by Shalini Kantayya relies on talking heads to expurgate a one-sentence thesis; a website is being used by an unsavory company. Simply shocking.

Framing Agnes looks to find objective truth in a too-subjective understanding of historical bigotry. In the end, we don’t learn anything that can be repeated without naming the filmmakers and their journey with the material, which negates our journey with the material.

W. Kamau Bell’s We Need to Talk about Cosby has a very necessary conversation in an entirely too broad tone. When Bell, our director/producer/narrator/editor/ostensible subject says that he’s a child of Cosby, he’s not kidding. He seems a hair afraid of laying his cards on the table at the outset. Where do you go if everyone knows the ending of the story…except we all know. Who needs to talk about Cosby, exactly? No one who’s going to watch this. It’s an important conversation, and it’s worth having, but it’s sure damning that it needs a four-hour documentary that holds your hand every step of the way, in case you didn’t believe the victims.

I think about the safety of the populist non-fiction form while watching Alon Schwarz’ Tantura, when a Jewish woman on death’s door is asked what harm it could do for the Palestinian authorities to look for a mass grave on a kibbutz. “If it’s important to them, it harms me.” The language of victors excited to close the door behind them when they die, surrounded by their loved ones and their lies. Schwarz’s film is at once a sequel to Shimon Dotan’s The Settlers, about the zealotry that informs the modern Israeli identity, but also a pretty rousing text about trying to prove facts today. When your opponent, in victory, still won’t let you chase scraps buried under their homes, what hope does truth have?

Reid Davenport’s excellent I Didn’t See You There dramatizes this by showing the ten thousand micro-confrontations he experiences as a man stuck in a wheelchair. People don’t know that, by laying cable in front of a handicap entrance, they’re literally stopping life from progressing. No one does unless suddenly they have to. I don’t believe it’s the purest mission of the documentary to make clear who suffers and why, but the flattening of the purpose of documentary filmmaking (and indeed the moving image itself) has made it a necessary component of the form. Now we do need to know what it means to be someone we share little in common with because the culture at large made it ok to ignore everyone who isn’t like you (Hnin Ei Hlaing’s well-argued and probably essential Midwives illustrates this quite nicely).

And no, I don’t mean in a Joe Rogan way. I think that the documentary landscape should adhere to the idea that the more we learn about ourselves and the world the better. That’s maybe the most boring thing about me, but I don’t think playing devil’s advocate is useful or interesting. Fifth graders can ask the questions of the worst of our “journalists”. Shouldn’t we hope to be able to do more? Isabel Castro’s heartbreaking Mija is ostensibly about two women trying to make it in America, but it becomes more than a simple story when two elderly people open envelopes containing their green cards. Then it’s not just fact; it’s truth.

Truth and fact go like lovers in the best documentaries. Rita Baghdadi’s enrapturing Sirens shirks an easy narrative about the first female metal band in Beirut and finds chaos and questions where cheerleading ought to be. Dos Estaciones by Juan Pablo González presents the inner workings of a tequila empire as if we were watching the villain of an English language anti-narcotics program, but it never gets around to condemnation or violence. The camera has a smooth confidence to go with its heroine, the lonely owner of this little fiefdom, who never looks to camera because she doesn’t have to. Everyone’s on the same page. Here’s what you don’t know; it’s cool and you’re wrong for demonizing the infrastructure America tells you is violent and unmanageable.

Sky Hopinka, maybe the best male filmmaker in North America under 50, played his latest, Kicking the Clouds, which shows in 15 minutes a continuity of malcontent in a violent, vicious country. Kathryn Ferguson’s Nothing Compares does the same and needs a third act, but it makes you want to stand up and sing and scream and be as angry as we all ought to be. Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes, a Robert Gardner-inflected study of two brothers helping the homeless, injured birds of their corner of Delhi, is likely the best film of Sundance 2022.

I personally love documentaries where you can’t fathom where a camera landed where it did to capture what it does. You don’t think to anyway; you’re too busy being dazzled, shrunk to a handful of dirt falling out of a fist. When you’re drawn in, hypnotized, thinking beyond the film, to life now and forever, to Gardner’s Forest of Bliss, where helping a defenseless creature separates you from the tumult of urban life, or life in general. You and the bird on your arm.

Truth. Reality? Who could say? Sometimes truth is enough.