Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableGarret Price processes the untimely death of Anton Yelchin through an intimate look at the actor’s mind, process, and struggles.

There’s nothing more shocking than the sudden death of someone far beyond their time. It’s especially harrowing when it’s someone you know, but strangely affecting still when it’s somebody you’ve only known through the pictures. In the case of Anton Yelchin, that sense of loss was particularly sharp: killed in a “freak accident” on June 19, 2016 in which his Jeep Grand Cherokee — a car that had been recalled for brake issues — pinned him to a brick pillar outside his home, Anton’s death seemed particularly senseless. He was a vibrant young actor, someone on Hollywood’s A-list despite balancing that out with vibrant indie projects and an arthouse sensibility of his own. In Love, Antosha, Garret Price‘s feature-length elegy for the young man, we get to see just how brightly he could have shone.

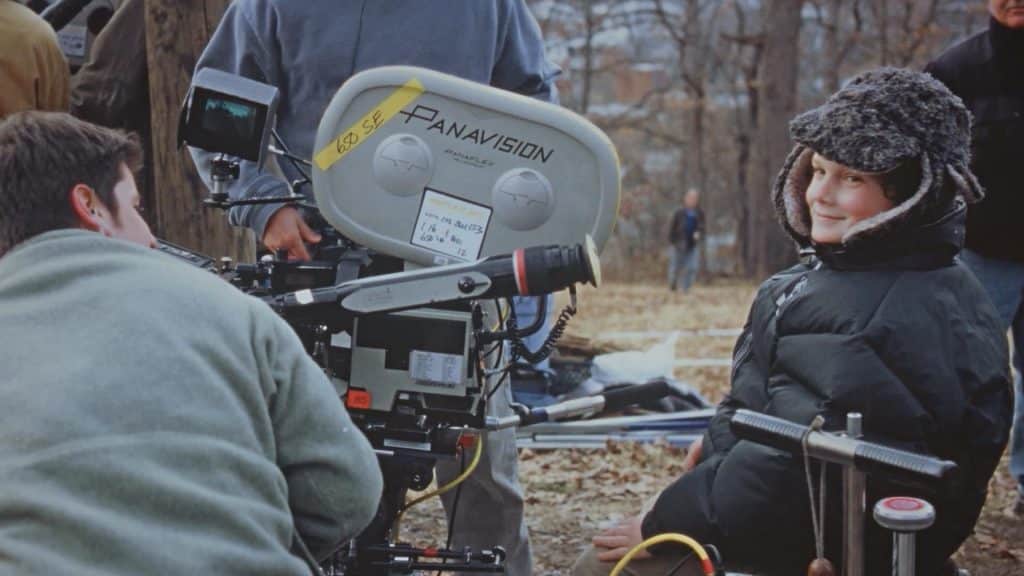

Living somewhere between collage doc and traditional profile, Love, Antosha chronicles Anton’s life and creativity from a young boy to the final moments of his life. From the opening shots, Yelchin is outed as an obsessive chronicler of his experiences: we’re privy to scores of home movie footage from childhood movies, hundreds of photographs from racy, slice-of-life photoshoots he’d take between films, scripts covered in scrawled character notes in every millimeter of the margins. He journaled extensively, Price using excerpts from that journal as a framework for the doc’s tale from childhood to death. In a fitting move, Nicolas Cage narrates these passages; it’s one of his most quietly outstanding performances in years, his aching intensity hinting at the kind of performer Anton might have become had he been granted a few more decades on this earth.

More than anything, you get to see how much of a student of cinema Yelchin was. As a child, his parents (Soviet-born figure skaters who fled the USSR to give their child a better life) educated him on the works of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and so on, building within him a burning desire to act, to create, to direct. And yet, he maintained this serious love of film without letting it turn him into a crazy film bro; at all stages of his life, even the most intimate footage of Yelchin reveals him to be a bright, exuberant kid, filled with humor and an incredibly generosity to friends, family and castmates alike.

But of course, Yelchin was not without his demons, both physical and emotional. It’s especially tragic to learn that, even without the accident that claimed his life, young Anton was running on borrowed time already: he had cystic fibrosis, diagnosed from an early age but only learning of it after his acting career started to take off in tweenhood. To fight it off, he had a strict regimen of breathing exercises and medication, and an incessantly positive attitude towards fighting his illness. One wonders if that helped instill the work ethic that would carry on into his prolific but all too short career.

Along the way, we’re privy to interviews from all manner of spectators to Anton’s life, from his parents (with whom he had a close relationship, especially his mother) to childhood friends, to many of his castmates from all manner of projects on which he worked. Most enlightening are interviews from his fellow Star Trek crew, especially Chris Pine, Zachary Quinto and John Cho, all of whom convey a certain kind of awe about him. No one lived or worked quite like him; he was almost pathologically dedicated to his craft.

He arguably subscribed to the ‘one for you, one for me’ model most A-list artists enjoy, where they slum it for big-budget paychecks to subsidize the challenging indie art they always wanted to make. While there are glimmers of that here (one telling clip of Anton on the red carpet zooms in knowingly on the “Smurfs 2” logo), he never let it show in his work, nor did he sacrifice an ounce of care or dedication to play, say, Pavel Chekov. “He could hold both the road traveled and the road not traveled in his head at the same time,” boasted Willem Dafoe, a testament to the man’s versatility.

More than anything, you get to see how much of a student of cinema Yelchin was.

Love, Antosha paints a portrait of a young star who steadfastly dedicated himself to being the best version of himself he possibly could. There are certainly warts in there: hints of wild parties, drug use, a riskily robust sex life. And yet, those are paired with little moments of generosity, like inviting childhood friends to international trips, or choosing not to budge while Chris Pine napped on his lap during a boat trip so he wouldn’t be disturbed. It’s an adoring tribute — one that possibly wallpapers over some of the boy’s flaws for the sake of propriety — but perhaps that’s how he should be remembered.

He was an artist, through and through, someone who truly committed his body and soul to creativity; a child star who entered adulthood as gracefully as one could imagine, especially given the invisible struggles Antosha brings to light. With him gone, we’re left only with his prolific, challenging body of work to contemplate who he was and what he could have been; Love, Antosha gives us a little bit more of the man behind the actor. And for that, we should be thankful.