KinoKultur is a thematic exploration of the queer, camp, weird, and radical releases Kino Lorber has to offer.

I have a confession to make. I thought this piece was going to be about something else. Probably yet another article extolling the genius of the French New Wave, arguing for the reconsideration of Jacques Rivette’s The Nun in light of the recent releases of Paul Verhoeven’s Benedetta and Mickey Reece’s Agnes. My prideful prejudgements are a sin. Thankfully, Elvis Presley and Mary Tyler Moore have shown me the light.

Movies about nuns are an intense distillation of social concerns about female agency. Convents are spaces where women sacrifice their choices to a greater good. While some have chosen the vocation for themselves, often others placed women there against their will. Once inside, social, sexual, and socio-sexual temptations confront them. This spiritual-physical split frequently leads to mental conflict. Individual and society questions about the limits of women’s self-control take center chancel, if you will.

This is the case with Rivette’s The Nun (1966). Based on the 18th Century story by Denis Diderot, the story opens on young Suzanne Simonin (New Wave darling Anna Karina) who doesn’t want to take her convent vows. When forced into the nunnery by parents trying to silence a family secret, Suzanne tries to rebel. In reply, a draconian sister assuming the role of Mother Superior starves and deprives Suzanne within an inch of her sanity.

Suzanne eventually files a suit against the convent. Though still under her parents’ control, Suzanne secures a transfer. Yet even this cloister comes with its own leering and lecherous dangers. By the time she can achieve independence and leave the convent, Suzanne finds the outside world equally limited. She must overcome her sense of spiritual and psychological futility or die.

It’s a devastating picture. Karina goes through it, swinging from fragile to feral in her pursuit of liberty. It’s a distinctly French existentialist look at the cruelty of institutions. Unfortunately, though it offers exceptional shot compositions, lead performance, and narrative poetics, there’s not much else The Nun offers that more titillating fare doesn’t provide. It’s a nunsploitation film that has learned its catechism, but its messaging never leaves the cloister.

Thankfully, Elvis Presley and Mary Tyler Moore have shown me the light.

This is, of course, somewhat ironic given that the famous ecumenical council known as “Vatican II” (1962-1965) primarily focused on opening up the Catholic church to make it more accessible and approachable to “the people.” That’s why Sister Mary Tyler Moore and two fellow nuns are knocking on Dr. Elvis’ door in Change of Habit.

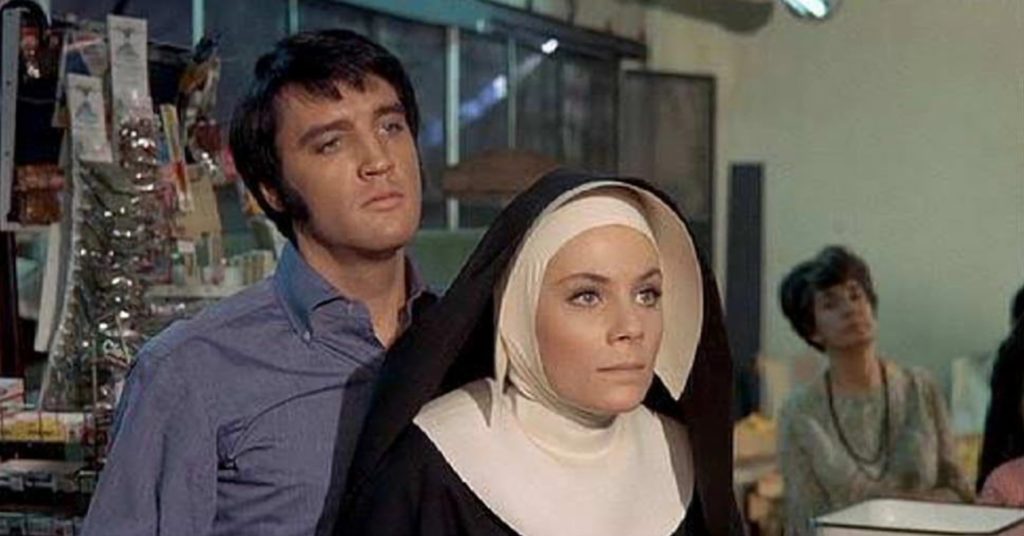

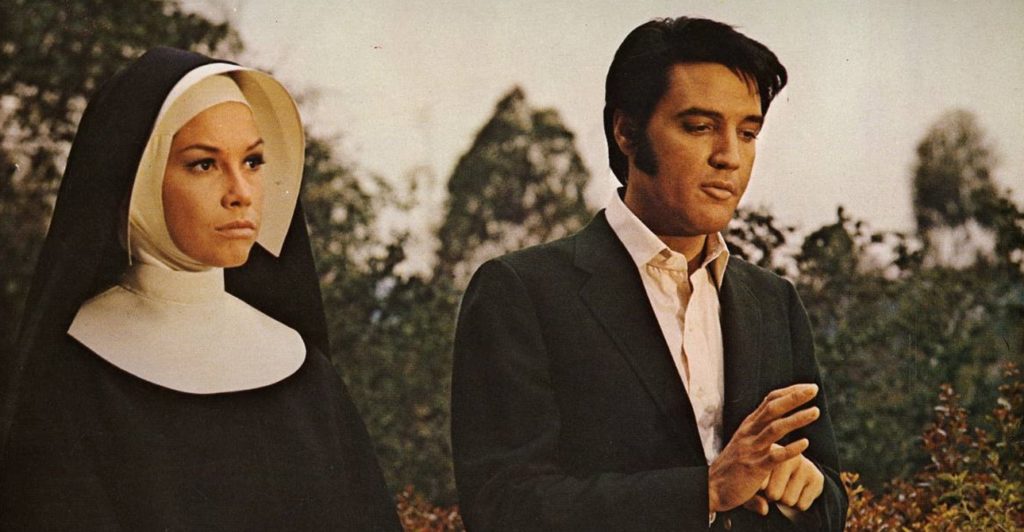

It’s the height of the groovy ’60s when Sister Michelle (Mary Tyler Moore) first enters Dr. John Carpenter’s (Elvis Presley) inner-city physician’s office. Arriving at a full-on jam session with an open shirt and diverse audience (including an uncredited appearance by vocal superstar Darlene Love), this doesn’t seem quite like the place she and her sisters had in mind. Instead, they were expecting a more orderly place for them to do their good works.

As Sisters Michelle, Irene (Barbara McNair), and Barbara (Jane Elliot) settle into the predominantly Puerto Rican area, they find their convictions tested. Barbara, the youngest, is still torn by a life of social isolation. Irene similarly questions her separation from other Black folks and the Black Power Movement. Being the purest and best at medicine, Michelle develops inevitable feelings for Dr. Carpenter.

Despite being Moore’s last film before television stardom and Presley’s final feature film before his death in 1977, each brings their signature magnitude to bear. Presley plays his age and has genuine moments of tenderness with his patient–extras and costars equally. Moore, McNair, and Elliot are self-possessed women with intelligence, wit, and depth.

This is partly because the script by James Lee (Roots), S.S. Schweitzer, and Eric Bercovici (Shogun) commits to social engagement, immersing its characters in their environment. Irene’s interactions with Black Panthers were, dare I say, shockingly nuanced for a late-60s Hollywood picture helmed by white men. It even handles Barbara’s desires for sexual and romantic liberation with an uncommon sensitivity. Finally, by giving Michelle an ambiguous ending, we’re denied the logic of most films of this ilk and certainly most Elvis films.

But it would be a sin to say this film is ideologically flawless. For example, Habit doesn’t handle the threat of sexual violence as delicately as possible. For every moment of social consciousness, there’s a moment of medical ineptitude. This is most uncomfortably true with little Amanda (Lorena Kirk). She receives a questionable autism diagnosis for being angry at the world following a traumatic event, something that sounds far more like Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Worse is the prescribed course–hold Amanda down until she can’t struggle anymore and hope love will “soothe her.” It’s hard to watch people be so dedicated to being scientifically incorrect.

Amongst a full convent of nunsploitation films, Change of Habit is certainly the most compassionate look at the church. In a way, it’s refreshing to see a genuine attempt to make The Church appear socially relevant. I wasn’t fully converted, but I did gain a little faith. Here is a film finally concerned with the social psychology of women rather than their psychosexuality. One that wants to show a repentant and changing institution rather than merely acknowledge its violence as some sort of fait accompli.

Even a kung-fu rape-revenge thriller like Revenge of the Shogun Women (1977)–also recently released by Kino–dedicates more time to the men in the village than its way more interesting fighting nuns. At least with Change of Habit, we get nuns who are human beings, not vessels of metaphors or fetish objects. By giving us these human nuns, we’re thrust into a stronger religious quandary about women’s agency within and via religion.

I’m not a religious person, despite my B.A. in Religious Studies. Still, I found it pleasing to see another film outside the Sister Acts offer socially in-touch nuns. It certainly changed my habit of skepticism towards “nice nun” films and challenged me to approach religion in cinema with a little more good faith.

The Nun, Change of Habit, and Revenge of the Shogun Women are now available on Blu-ray courtesy of Kino Lorber.