John Landis’ first film may embarrass him, but it retains an undeniable charm.

When you insert the Blu-Ray of Schlock, John Landis’s 1973 directorial debut, the first thing that comes up—even before the menus—is a brief clip of Landis himself informing you of the film you are about to watch. He concludes by sheepishly adding, “I’m sorry.”

You can get where he’s coming from. The film is so goofy and ramshackle that it often threatens to fall apart before your eyes. There are Ritz Brothers movies that have stronger narrative structures and visual finesse. Nonetheless, it has a certain loopy charm that shines through. Combined with the unusual circumstances surrounding its very existence, that makes it worth checking out to this day. Even if Landis might prefer you didn’t.

Landis had already dabbled on the fringes of the film industry. He’d put in time on jobs ranging from working in the mailroom on the Fox lot to serving as a production assistant on the Clint Eastwood war epic Kelly’s Heroes (1970) to appearing as a stuntman in several films that shot in Europe in the late Sixties by the age of 21. So, in 1971, he decided to make a movie, utilizing funds he scraped together from others and his own savings.

Like so many others, he figured that the way to go was to make a horror film. They’re cheap and generally don’t require big stars. Assuming the results were not completely disastrous, making a few bucks in the day when grindhouses and drive-ins were looking for cheap product was nearly assured.

Instead of going the serious route, Landis pursued a more absurdist approach. The director looked to no less a film than Trog, a deeply bizarre 1970 effort from Freddie Francis about an anthropologist who discovers a troglodyte in a nearby cave, for inspiration. None other than screen legend Joan Crawford in what would prove to be her final role played the doctor. Yes, she was slumming, but you have to give her credit. Even when stuck in a cheese ball monster movie that had her skulking around a cave while calling out “Trog! TROG!” she still gave it her all in the manner of a true star.

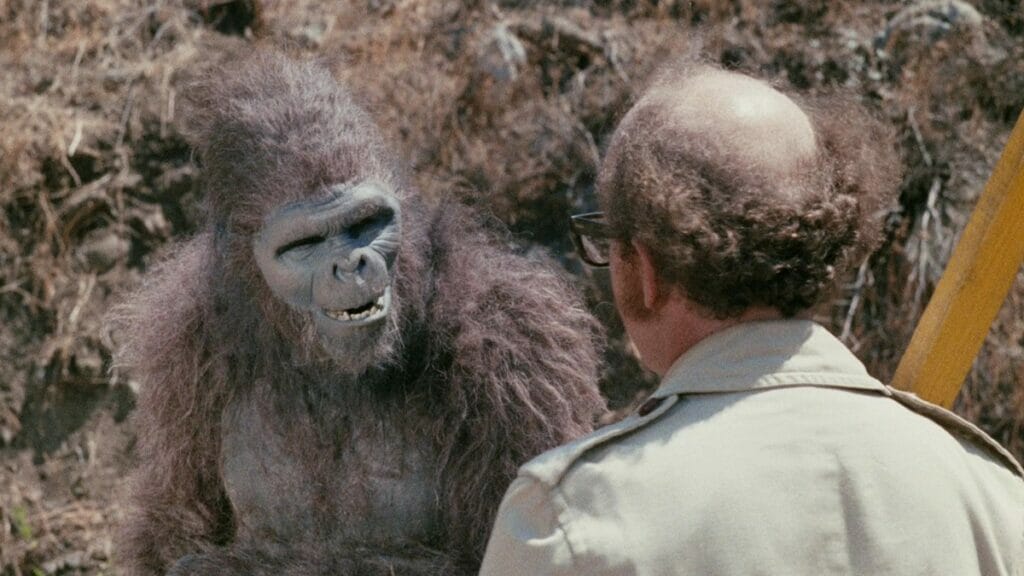

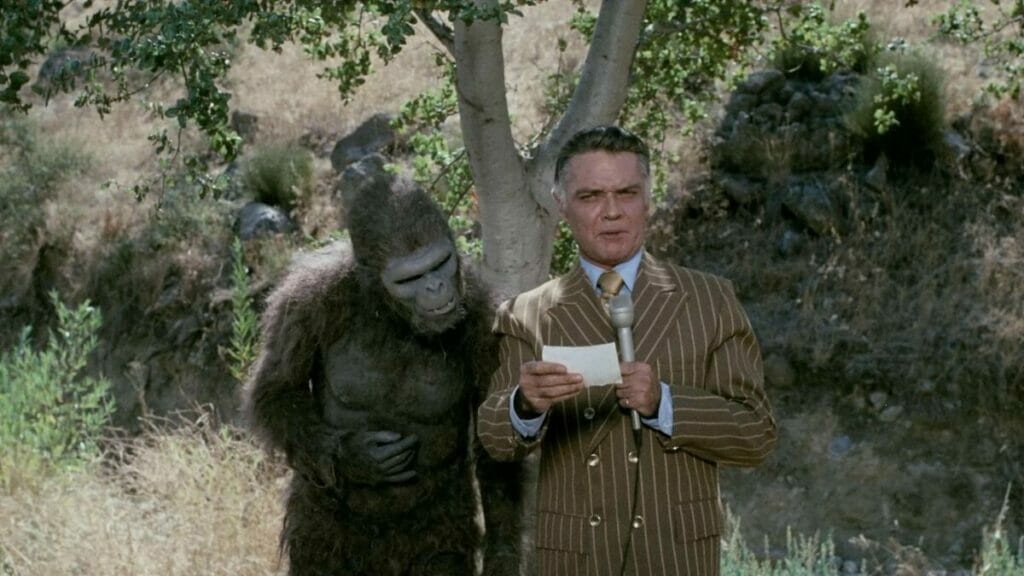

In Landis’s variation, a prehistoric apeman, the titular Schlock (played by Landis himself), terrorized Southern California. After emerging when teens disturb his cave, things inevitably go murderous, albeit in a decidedly PG-rated way. Schlock’s rampage leads him to a nearby suburb. There, he meets and falls in love with blind teenager Mindy (Eliza Garrett). She shows him kindness, mistaking him for a dog. That all changes when she regains her eyesight.

By most accepted critical standards, Schlock is, of course, complete nonsense.

While the authorities pursue him, Schlock wanders around town and gets into a bunch of goofy misadventures. He wanders into a movie theater, rips a car apart, does a piano duet, and messily shares a cake with adorable twin girls and a dog. He caps it off by climbing to the top of a building with Mindy in tow. This leads to the inevitable final battle with the military and a couple of famous movie quotes (one inevitable, one less so). The surprise final reveal of the Son of Schlock caps things off.

By most accepted critical standards, Schlock is, of course, complete nonsense. While those innately familiar with Trog will be amused with Landis’s piss-take on that film’s lunacies. On the other hand, those who come into it cold will likely be baffled by much of it. And if they struggled with that, imagine their reaction to the part spoofing the then-popular Elvira Madigan. What passes for a plot unfolds in such a lackadaisical manner that there are times when it feels more like a collection of skits along the lines of Landis’s 1977 follow-up, The Kentucky Fried Movie. It consistently feels more like a slightly more elaborate variation of things that movie-mad kids used to make in their backyards with a borrowed camera, a dog-eared joke book, and extremely patient friends and/or relatives.

And yet, if you are willing to forgive the film’s numerous trespasses, it maintains a certain undeniable charm that’s lasted for the half-century since its original release. There is an amiable spirit to the whole enterprise. For instance, even when Schlock rips off a reporter’s arm, the moment is completely bloodless and played for cartoonish laughs. (The arm, by the way, was developed for one of the most famous moments of the hugely popular thriller The Andromeda Strain.) The tone is aided in no small part by Landis’s amusing performance as the title creature. He comes across more like Oliver Hardy than King Kong.

The best thing about the film is the contribution by the other soon-to-be-famous name making their debut, makeup artist Rick Baker. Also only 21 at the time, Baker still lived at home with his parents. He used his mother’s oven to bake the foam rubber molds to create the Schlock suit.

Although a far cry from the ape suits that he would later create for such films as the 1976 version of King Kong, The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981), Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan (1984), Gorillas in the Mist (1988) and the 2001 edition of Planet of the Apes, it is a far more impressive creation than one might expect to find in a film of this caliber and budget. Even better, it is silly enough to fit in with the movie’s cartoonish spirit. While Baker would go on to become one of the most celebrated makeup artists in Hollywood history, this film proves he was pretty much aces at his job right from the start.

[F]or all the amateurishness on display, there is something about its earnest goofiness that allows one to forgive its occasional dull moments and misfired gags.

After the film’s completion, Landis tried to sell it to the studios, but they all initially rejected him. The only nibble was reportedly Roger Corman, with the stipulation that Landis would shoot a few additional scenes including nudity. Landis held out, and eventually, legendary B-movie producer Jack H. Harris offered to release it. However, he had terms as well. He requested Landis add another 10 minutes and threw in clips from a couple of films that he owned, The Blob and Dinosaurus, to boot.

Landis agreed, adding the theater and car-trashing scenes. Still, the film continued to languish until 1972. That’s when someone working for The Tonight Show got wind of Schlock and arranged for Johnny Carson to see it. Carson dug it and went so far as to have Landis as a guest due to the novelty of a film directed by a 21-year-old, though Landis was 23 by that point. The appearance helped it to finally secure a release the following year.

The film wasn’t a hit at the time. Landis would spend the next several years doing odd jobs–from working as a stuntman on Death Race 2000 to working on the script for what would eventually become the James Bond epic The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)–until the Zucker-Abrahams-Zuckerberg triumvirate, recalling his appearance with Carson, contacted him. The job was directing the aforementioned film version of their stage revue, Kentucky Fried Movie. Next came a little thing called National Lampoon’s Animal House, which revolutionized American film comedy. As Landis’s star rose, Schlock would eventually develop a small cult following.

Obviously, Schlock is no one’s idea of a classic comedy. Even by micro-budget directorial debut standards, it is uneven. At least at under 80 minutes, it doesn’t linger around long enough to wear out its welcome, though. And yet, for all the amateurishness on display, there is something about its earnest goofiness that allows one to forgive its occasional dull moments and misfired gags.

Landis may be vaguely embarrassed by the whole enterprise nowadays but trust me, he has made worse movies. You have DEFINITELY seen worse ones. Landis scraping together the resources to make his very own movie at such a young age is a bit of a miracle. That it still sort of holds up a half-century down the line is perhaps an even bigger one.