Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableCW: The following review involves discussion of sexual abuse and assault that some readers may find activating.

Don’t speak up. Just make breakfast. And get the men their plates. Go find some charcoal. Stop challenging the rich. Don’t be depressed in public. Don’t speak up for yourself. Just act like everything’s fine. Put the eggs in the basket. Why aren’t you more traumatized? Don’t talk about the video. “There are some things you cannot challenge.” Don’t talk about it. Don’t speak up. Did you get everything for breakfast tomorrow? Focus on that. Don’t cause trouble. Be a “proper” woman. These phrases inundate Shula (Susan Chardy) in writer/director Rungano Nyoni’s On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, a fantastic follow-up to her outstanding debut, I Am Not a Witch.

The film opens with her stumbling on her Uncle Fred’s corpse while coming home from a costume party in an inflatable bodysuit. Initially, Nyoni’s Guinea Fowl script seems poised to use this unexpected loss to unspool a dark comedy. After all, stranding her in such an outsized outfit for an entire night by the body does much of that work all by itself.

That tone deepens as Shula’s relatives congregate in one house to mourn Fred. The stream of overbearing and obliviously toxic uncles, aunts, cousins, and more intrude channel something more akin to Shiva Baby as it wrings intensity and grim gags out of strained familial relationships.

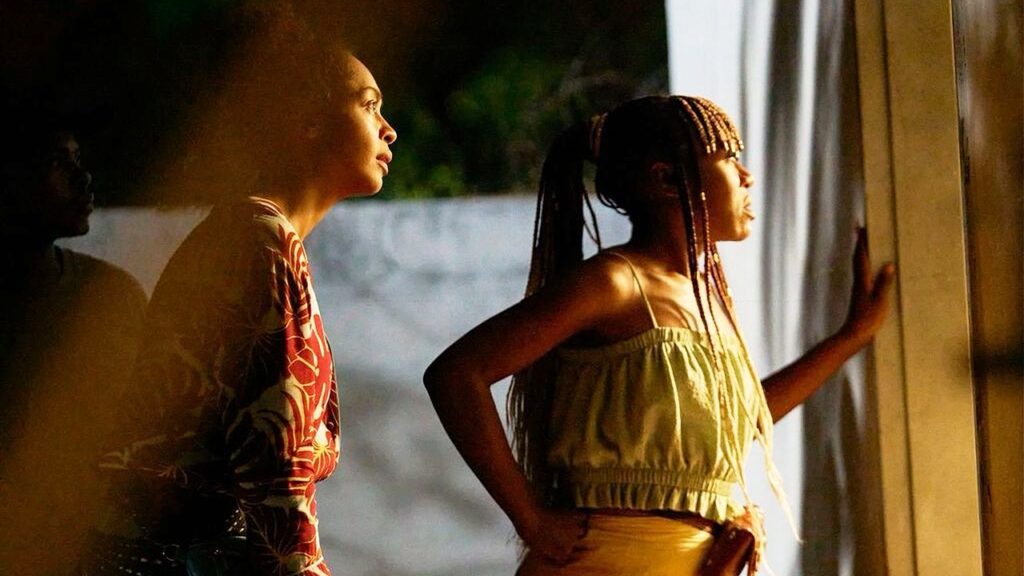

However, from On Becoming a Guinea Fowl’s start, there’s something darker in Shula’s eyes. Chardy is magnificent at conjuring up pupils that exude immediately tangible caked-in exhaustion. They betray the truth. Grappling with harrowing personal turmoil has left Shula utterly drained. The film confirms that subtext as she walks with cousin Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) to get charcoal. Nsansa drunkenly recalls how Uncle Fred took her to a cabin to molest her. Despite the horrific nature of the incident, Shula’s cousin recounts it with laughter, joking about Fred’s flaccid genitals.

While Shula admonishes her for making light of her trauma, it speaks to their reality. When everyone else around them refuses to acknowledge Fred’s massive flaws, a repeated pattern of sexually abusing minors chief among them, how else can Nsana react than filter his evil actions through a dismissive lens?

Shula and Nsansa come from a middle-class Zambian family wired to protect their false but idyllic vision of the world. To do so, they accept certain perspectives as unshakeable facts. Prayer solves everything. Girls and women are always at fault. Individuals in lower economic brackets are, by default, enemies. These are the tenets of existence, suffocating the experiences of Shula, Nsansa, and others.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl’s deeply evocative imagery thoughtfully renders the complexities of navigating everyday life while grappling with both sexual trauma and dehumanizing societal norms. Nyoni and cinematographer David Gallego are especially adept at communicating Shula’s tormented psyche through striking images and precisely orchestrated camerawork. A dreamlike visual motif of Shula constantly wandering halls and rooms flooded with a few inches of water vividly communicates what it’s like for her to navigate everyday life with sexual trauma hovering over her brain. She can still walk and talk, but the trauma is always there.

Meanwhile, Nyongi and Gallego fascinatingly frame certain scenes to avoid showing the front of Shula’s head. The eyes are the window to the soul, as they say. Keeping this part of Shula’s form off-camera for specific sequences indicates how the people around her deny her essential humanity. A wide shot depicting Shula answering a deeply personal question from her father on the phone provides a particularly haunting example of this motif. Cutting everything from Shula’s shoulders up devastatingly frame communicates the father/daughter dynamic as one of immense emotional distance.

Nyoni’s precise and heartbreaking script frequently pairs well with its rich visual language. A scene of Shula trying to talk to her mother about childhood abuse while they’re picking eggs shatters the soul. Bathed in the chicken coop’s bright red light, her mom repeatedly fails Shula by changing topics to outrun the truth. Memorable flourishes like that marry captivating drama and masterful visuals in a potent combination.

The talented actors execute this heavy material with effortlessly lived-in realism, even when they have only a sliver of screentime. Chardy’s lead performance, for instance, provides a fantastic anchor for On Becoming a Guinea Fowl. That said, even amongst a collection of tremendous performers, Chisela emerges a standout. Initially, she gives the film a lively comedic counterbalance to the buttoned-up Chardy. As Nyoni’s screenplay pulls back the curtain on Nsansa, though, Chisela’s performance truly comes to life. She proves equally graceful at manifesting intimate grapplings with her trauma and nailing oversized comedic lines. The vast emotional tableau within Chisela’s performance is nothing short of transfixing. Speaking of unforgettable supporting performances, Esther Singini as a third cousin, Bupe, is also remarkable. She sublimely depicts the college-aged woman at both her most vulnerable and her most artificially “fine”.

Shula does not hear a lot of empathy in her everyday life. The demands of her male relatives, even those as simple as not having to retrieve their own plates of BBG, erase her needs, trauma, and autonomy. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl delivers a phenomenally rendered opposition to those societal norms. Equally outstanding imagery and towering performances realize the complicated lives of ignored sexual abuse survivors. Here is a movie unafraid to speak up and make itself heard, much like the calls of its titular bird.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl opens in theatres on March 7.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl Trailer: