The first of M. Night Shyamalan’s Eastrail 117 trilogy frustrates with its approach to superhero comics as a medium but excels in its drama-and-thrillcraft.

Unbreakable is as of its time as a movie can be. Released in 2000, when comic movies were in the public consciousness enough to justify committing a big budget and stars, but not so successful that they felt impersonal or routine. It was M. Night Shyamalan‘s fourth movie and, in a way, his second. After Praying with Anger (which never left the festival circuit) and Wide Awake failed to make much of a critical or box office impression, The Sixth Sense tapped the underserved audience for austere, adult sci-fi/fantasy thrillers to the tune of nearly seven hundred million dollars and six Oscar nominations.

Unbreakable, like its predecessor, starred Bruce Willis—arguably at the peak of his powers between The Sixth Sense and 1998’s Armageddon, alongside frequent and always welcome costar Samuel L. Jackson. The feeling was that the actor/director team of The Sixth Sense and the costars of Pulp Fiction and Die Hard with a Vengeance knew what they were doing and had earned the right to be left alone. The result was an uneven film that spotlighted Willis and Shyamalan at their best while also serving as the conclusion to one of the most exciting phases of Willis’ career and exposing the cracks that would undermine Shyamalan’s work for the better part of a decade.

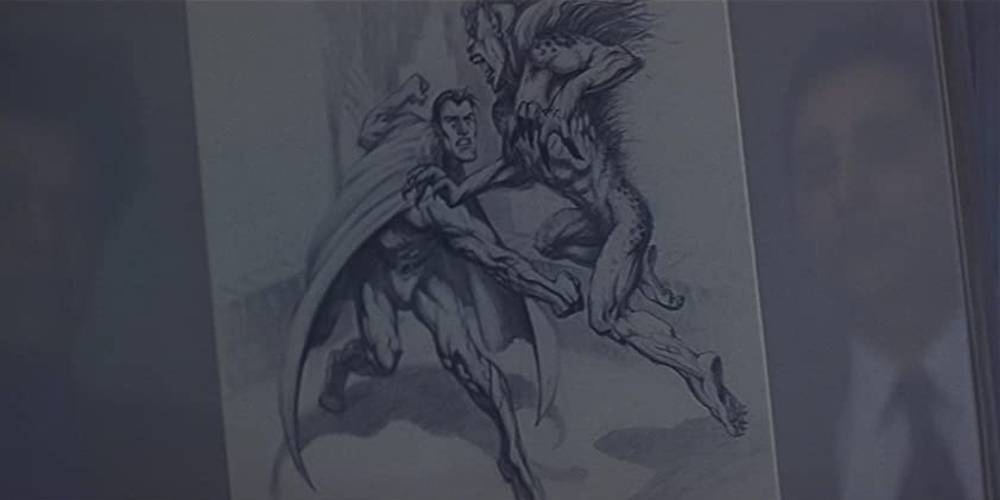

The most comic book movie not based on a comic book ever made (yes, including The Incredibles), Unbreakable is an origin story for reluctant superhero David Dunn (Willis) and his friend/archenemy Elijah Price (Jackson). Price, a comic art dealer, tracks Dunn down after learning that Dunn is the sole survivor of a terrible train accident. Afflicted with brittle bone disease from birth, Price has long believed that he must have an opposite somewhere—someone who is invulnerable where he is hyper-fragile. Price also believes that superhero comics contain the secret history of these unbreakable people, distorted and sensationalized for the masses. Dunn understandably believes Price is a babbling maniac, but his twelve-year-old son Joseph (Spencer Treat Clark)—frantic for a way to bond with his subdued and detached father—thinks otherwise.

The tension in the early family scenes—especially Joseph’s clear yearning to be part of his fathers’ life—is almost unbearable.

Running at a brisk hour and forty-seven minutes, Unbreakable feels longer than it is. Shyamalan uses long takes that let scenes grow gradually. Combined with a highly reserved lead performance from Willis and a less-reserved-but-still-pretty-restrained performance from Jackson, these compositions give Unbreakable a solum, thoughtful air—one that plays best in its domestic scenes. David is a quiet, careful man who never lets anyone get too close to him, including his wife Audrey (Robin Wright) and Joseph. When the story opens, the Dunn marriage is on the verge of collapse: husband and wife sleep in separate rooms, and David travels to New York to interview for a job that would take him away from his wife and child. The tension in the early family scenes—especially Joseph’s clear yearning to be part of his father’s life—is almost unbearable.

Shyamalan’s depiction of a family in crisis is as sharply focused as in The Sixth Sense. Tiny moments like David and Audrey both knocking on each other’s bedroom door before entering or the camera zooming out from David in bed reading to reveal Joseph asleep next to him, clutching his father’s chest like a giant teddy bear, are magnificent. It’s so well realized that you want to ask if everything’s alright at home. Likewise, a flashback to Elijah’s childhood, where his mother tempts him to venture outside by leaving comics on the bench in the park across the street, wonderfully explores Elijah’s reverence for both his comics and his mother.

Unbreakable’s serious approach is less successful on its superheroic side. It starts well enough, with Elijah and Joseph encouraging David to consider the fantastic possibility that he is, in fact, invulnerable. But after a while, Shyamalan’s shortcomings as a writer make it hard to take the story’s solemnity seriously. As a visual stylist, Shyamalan is as good as anyone in his generation. His movies are striking, well-staged, and lovely to watch. Unfortunately, his scripts often lack the care and attention to detail he lavishes on his frames. He knows what makes a good story but rarely seems to have the patience to sit down and write one. As a result, Unbreakable often feels shallow and half-baked.

Take, for instance, Dunn’s power set. His strength and invulnerability have a certain comic-book logic, but he also possesses a kind of psychic alarm system that allows him to get flashes of the people around him and their assorted sins. It’s a power wholly disconnected from his physical abilities. I’ll buy that if there’s a super brittle guy, maybe there’s a super dense one too, but the psychic thing comes out of nowhere and mainly exists for Shyamalan to set Dunn up for a dramatic final confrontation with a madman who doesn’t have anything to do with what’s came before. Also, if David gets these flashes by bumping into people, wouldn’t it stand to reason that he’d have experienced it before he met Price? The movie gestures towards the notion that Dunn’s been unconsciously suppressing his powers—a reflection of his detached personality and vice versa—but it mostly feels like a plot contrivance.

Similarly frustrating is Price, whose characterization feels half-formed and unfocused. He’s supposed to be a comic book maniac, a man whose entire life has been lived through the colorful stories he reads. But his thoughts on them are as basic as it gets. Yes, superheroes often have square jaws and supervillains’ crazy eyes—that’s not the observation of a devotee obsessed with the medium. That’s something someone who spends five minutes in a comic book shop could tell you. Later, Price falls into a near-catatonic depression when David explains that he can be hurt—via water. But after glancing at the cover of a comic, he realizes, “Eureka! Superheroes always have a weakness!” Which, again, yeah.

…even though Unbreakable’s superhero side is shaky, Shyamalan’s fourth film is ultimately a success—as best seen in the strength of the Dunn family story and a genuinely exciting climactic fight.

Making wild guesses about the nature of reality based on a comic book cover would be okay if Elijah was a crackpot, but he’s basically correct every time he opens his mouth. He believes that he has an opposite number with super strength and that David Dunn is that opposite, and he’s correct both times. He diagnoses David’s One Weakness after looking at the cover of a comic book and correctly assumes that David’s hunches about people are low-level psychic abilities. He says he knows things and talks about what he’s learned, but we never really understand how he came to this knowledge. There’s no scene like Morgan Freeman staying up all night in the library researching in Seven or appealing to some wise mentor figure who’s passing down ancient, obscure information like Kris Kristofferson in Blade.

Those lapses in logic and fuzzy characterization can work in a lighthearted romp designed chiefly to be a good time. You don’t need to wonder just where Spider-Man’s webs are sticking that he can comfortably swing right down the center of a street because we’re too busy having fun watching him flippin’ and thwippin’ and quippin’ to worry about details. But a movie where a crying eleven-year-old points a loaded gun at his father in the family kitchen in a desperate attempt to prove he’s invulnerable inherently demands more attention to detail.

That’s a capital-G Great Scene, by the way. So is the scene where Joseph keeps adding weight to David’s barbell to test his (nonexistent) limits, and the flashback that opens the movie showing a wailing, newly born Elijah being diagnosed with broken arms and legs by a shaken doctor. But the emotional investment those scenes elicit doesn’t jibe with the sloppier parts of Unbreakable’sstorytelling. It’s a challenge inherent to super heroic storytelling that was most recently on display in Zack Snyder’s DC films: the more serious and “realistic” a story, the more pronounced the nuttiness becomes. At the end of the day, you can’t make a “realistic” movie about a guy who dresses up in a costume and fights crime without it slipping into the realm of unintentional comedy. Christopher Nolan, for instance, made sure that a steady pulse of dry wit ran through his Bat Trilogy, usually courtesy of Michael Caine’s Alfred. Shyamalan inadvertently forces the audience to make observations the film is desperate to avoid by removing any acknowledgment of how outlandish this all is.

But even though Unbreakable’s superhero side is shaky, Shyamalan’s fourth film is ultimately a success—as best seen in the strength of the Dunn family story and a genuinely exciting climactic fight. Willis and Jackson make excellent foils for one another, with Jackson’s florid language and striking appearance contrasting Willis’s drab costume and quiet, monosyllabic dialogue. Knowing that Willis retired from acting in 2022 due to aphasia, it’s hard to look at his minimalist performance here and not look for early signs. And while Willis would do exciting work in the 2000s and early 2010s—particularly in Sin City, 16 Blocks, Moonrise Kingdom, and Looper–Unbreakable is the end of an exciting, productive phase in his career.

After Unbreakable, Willis seemed less interested in working with bold, distinctive talents like Tarantino, Gilliam, Besson, Bay, and Shyamalan, whose work capitalized and subverted his tough guy movie star image. Instead, he seemed content to churn out anonymous B-level action movies like Tears of the Sun and Live Free or Die Hard, along with unremarkable indie offerings like Alpha Dog and the unfortunately titled Lucy Number Sleven. But separating his opposing desires to be a quirky character actor and also a square-jawed meat and potatoes movie star robbed him of the tension that made him so interesting in the first place. Willis was unique among his peers in that he could deliver forgettable pap like Striking Distance, action classics like The Last Boy Scout, weirdo arty/mainstream movies like 12 Monkeys, and jaw-droppingly bad ideas like Color of Night all in the same ten years. You never knew what you would get with him in the 90s, and after Unbreakable, he seemed to have mostly lost his desire to surprise people.

As for Shyamalan, his mix of elegant presentation and pulp genre would serve him well for exactly one more movie before audiences and critics tired of his high concept/low logic offerings—leading to a very public fall from grace and descent into critical and popular ignominy that lasted more than a decade. He never did figure out how to write a well-crafted script to match his meticulous direction, but his recent ventures into the more disreputable world of minimalist grindhouse-adjacent horror have proven a good fit for him. The mode allows him to let his sensational impulses run wild without worrying about trying to please blockbuster audiences or becoming a critical darling. Still, it was interesting there for a minute to watch him make Highly-Personal-Oscar-Bait/Extended-Twilight–Zone-Riff/Grandiose-Blockbuster-Entertainments. That’s the kind of bold ambition that we can always use more of.