In the Cut sees the great director delve into New York’s anxious days post-9/11 via a thriller about a woman unsure who she can trust.

Many of Jane Campion’s most famous works are period pieces: The Piano and The Portrait of a Lady in the 1990s, Bright Star in the 2000s, and The Power of the Dog in the new 20s. Oftentimes, Campion will root her projects in the past as ways of showing how thorny emotions like erotic attraction have always been around in society. The same holds true for humanity’s more vicious side—its smug pretensions and cruelly constricting gender norms.

Under Campion’s insightful gaze, the past and present are bridged, inviting viewers to recognize themselves in characters who lived and died long ago. But while Campion’s most famous films have dealt with the past, it isn’t her exclusive purview. Her 2003 thriller In the Cut is both set and deeply rooted in the then-present. She continues exploring the themes that have fascinated her throughout her career but she does so through the unique shape of the modern world.

Based on a novel of the same name by Susanna Moore (who also penned the screenplay with Campion), In the Cut centers on English teacher Frannie Avery (Meg Ryan). Frannie’s life is no picnic. Her love life has no pulse to speak of. One of her students is writing an essay about how John Wayne Gacy was innocent. And then a woman’s severed arm shows up in her yard.

Perhaps the most important part of In the Cut’s distinctly 2003 ambiance is the lingering effect of 9/11.

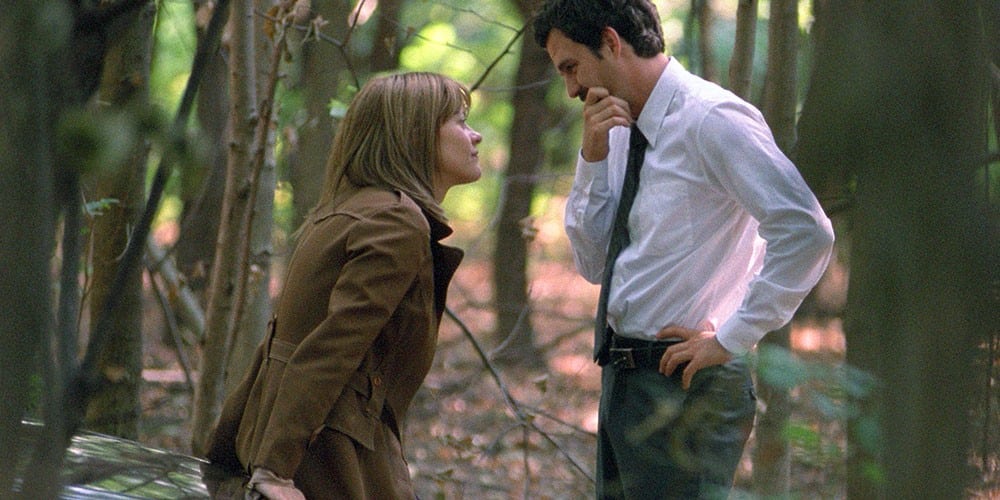

The severed limb leads to Frannie meeting detective Giovanni A. Malloy (Mark Ruffalo). Though abrasive and far from perfect, there’s something tantalizing about Malloy’s demeanor. Frannie swiftly finds herself infatuated with him. Despite their newfound romance, her constant run-ins with potential clues and incidents tied to the local murderer will lead her to wonder who, if anyone, she can trust.

Frannie’s life unfolds amidst the modern New York City landscape, a setting that dramatically contrasts the vintage international settings of her earlier films. The city setting enables Campion to build a unique claustrophobia into her filmmaking. The sparse beach of The Piano and expansive wealthy domiciles of The Portrait of a Lady are traded out for bustling streets and cramped apartments. In the modern world, space is a luxury, and Frannie’s life reflects this. She’s always shown to be cramped not only physically, but also by the potential dangers of men lurking in both the shadows and positions of power.

It’s just one of many unique 21st-century elements that could’ve never existed in Campion’s prior works set in various parts of the 19th-century. Familiar tunes play diegetically throughout In the Cut reinforcing internal emotions and perspectives. It would’ve been difficult for The Piano to underscore Holly Hunter’s plight with Willie Nelson’s “I Just Can’t Let You Say Goodbye” or Macy Gray’s “Relating to a Psychopath.”

But in the bustling world of In the Cut, popular music is an organic part of the texture and simultaneously functions as another indicator of how life always continues around Frannie. And Campion deploys her needle drops to wonderfully unnerving effect. The conventionally bubbly song “I Think I Love You” contrasting the sight of Frannie recovering from the sudden and brutal loss of a loved one is especially evocative. the ditty taunts the tormented Frannie with reminders of the happiness and peace that now evades her.

The thoughtful use of familiar radio staples is not the only way In the Cut smartly roots itself in the modern world. Its camerawork also reflects the hurried nature of existence in 2003. The visuals take on a handheld quality evocative of cinema verité features. Some of this is attributable to the more portable cameras Campion is using here, like the Moviecam Compact, which do lend a distinctly modern look to the proceedings. It makes for a striking contrast to the flashback scenes, which depict Frannie’s father courting a lady in a sepia tone. The old-timey nature of these glimpses into the past is reinforced by the tiniest visual details—capturing everything through a higher frame rate or maximalist dialogue-free performances of the actors.

These visual choices build a firm barrier between the past and present within In the Cut. The Piano and The Portrait of a Lady so immersed viewers in a colorful, nuanced past that their long-past settings were as immediate as today. With In the Cut, meanwhile, Campion wants the delineation between past and present to be clear and explicit. Frannie’s vision of the past is based more on a cutesy story from her father than an actual memory. Campion and cinematographer Dion Beebe ensure that this is clear to their audience

Perhaps the most important part of In the Cut’s distinctly 2003 ambiance is the lingering effect of 9/11. The aftereffects of the day loom large over the picture. Frannie’s paranoia about who to trust and the elusive nature of the killer feel extra palpable in the wake of the attacks. Even her initial dismay, but not extreme shock, upon learning that somebody in her apartment complex has been gruesomely murdered, reflects how familiar horrific violence had become for New Yorkers post-9/11.

Much like Spike Lee’s 25th Hour, In the Cut‘s timeless themes take on extra resonance when viewed in this context. Few things are as distinctly early 21st-century as that atmosphere; a city and its people known for enduring suddenly grappling with feeling vulnerable, even adrift. This undercurrent lends a haunting quality to even In the Cut’s tenderest moments—the quiet moments of positive connection between Frannie and her adopted sister Pauline Avery (Jennifer Jason Leigh). Clinging tightly to someone you love feels all the more vital in the wake of all this loss.

Though deeply rooted in the 21st-century, In the Cut remains interested in Campion’s favorite themes and motifs as her period work. Most notably, the casual homophobia and cruelty in “jokey” comments from Malloy and his fellow police officers feel like a precursor to Phil Burbank’s hardcore cowboy act in The Power of the Dog. In both contexts, Campion uses macho language to demonstrate how societally acceptable forms of masculinity are built on oppressing others. While this provides a sense of bonding for dudes, it leaves people outside of that gender like Frannie feeling like they’re intruding on reality itself.

Skewed machismo bleeds into everything in In the Cut, to the point that it defines Detective Richard Rodriguez’s character (played by Nick Damici) even before he’s formally introduced when Malloy relates the story of how Rodriguez nearly murdered his wife when she caught him cheating as a nifty yarn. With this language, Campion delves into violence as the gateway to “ideal” manhood, one in which any sense of empathy or deviation from societal standards is to be ridiculed. These are the laws of the land, which echoes of the viciousness practiced by Sam Neill’s Alisdair Stewart in The Piano and Benedict Cumberbatch’s Phil Burbank in The Power of the Dog.

Conversely, another key aspect of Campion’s film craft is erotic attraction depicted through a female gaze. She deploys it to fascinating effect in In the Cut. Malloy is frequently the object of Frannie’s affectionate ogling, complete with an added layer of neo-noir style. While he can dazzle Frannie with his small talk and giving nature in bed, shots of Malloy are also often framed in a cold, unnerving way to reflect how she’s uncertain if she can trust him. Much like a femme fatale in a classic noir, Campion frames Malloy as someone that could steal or shatter your heart, or perhaps both.

Despite the new temporal and narrative context, Campion’s unflinching interest in eroticism is just as apparent as ever in In the Cut. This includes her welcome penchant for capturing the full-frontal nudity of well-known male actors (Harvey Keitel to Benedict Cumberbatch to, in this case, Mark Ruffalo). While Cumberbatch’s full-frontal moment in The Power of the Dog captured a fleeting moment of freedom and pleasure for Phil, the brief nudity from Ruffalo in In the Cut compliments similar nudity from Meg Ryan. It showcases their connection, the bond they’ve developed, and the ways they can be vulnerable with one another.

In the Cut is far from a perfect movie—yet again Campion fails to do right by characters of color. At its best though, it pulls off the impressive feat of establishing a unique identity amongst her films, one rooted in the modern world, one that uses Frannie’s escalating sense of uncertainty to capture and reflect the similarly anxiety-ridden atmosphere of New York City in the wake of 9/11. In the Cut is both a distinctly 21st-century work and unmistakably of apiece with Campion’s beloved period pieces.