Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableFrancis Ford Coppola’s final film to date may not be his best (or even good), but it encapsulates his yearning for creative freedom.

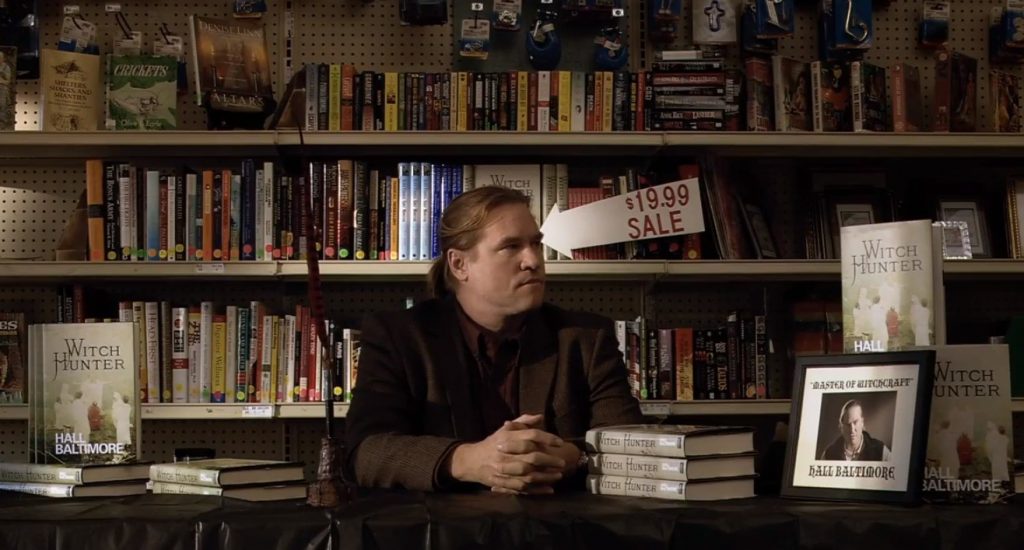

Pulsating at the heart of Twixt are pains all too familiar to legendary writer-director Francis Ford Coppola. Third-string horror novelist Hall Baltimore (Val Kilmer), the “bargain-basement Stephen King,” arrives for a book signing in the town of Swann Valley, where, unappreciated and unable to overcome a case of writer’s block, he’s forced to confront his insignificance, his sullied legacy, and the feeling that he has nothing valuable left to say or give.

Coppola, whose star from the days of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now had long since faded in the eyes of the public, and indeed in the eyes of many critics too, would certainly have known, stewed upon, and grappled with those same fears. Baltimore is also scarred by, and is yet to fully reckon with, the devastating death of his daughter in a boating accident, a detail that echoes the tragic passing of Coppola’s own son, Gian-Carlo, in 1986.

If Twixt, released back in 2011, is to be the last film that we ever get from Coppola, it’ll be a fitting, maybe even perfect swan song for one of cinema’s most incessantly imaginative maestros. It’s not that the film is Coppola’s best (far from it), nor does it represent the culmination of all of his aesthetic ambitions. What it does represent is the fruit of the total creative emancipation that he’d always been after—following a 10-year hiatus from filmmaking, during which he’d reaped the lucrative crop of his Napa Valley winery, he finally had the financial freedom to make intensely personal, aggressively experimental films purely on his own terms, extricated from the yoke of commercial pressure.

It also represents a sort of poetic return, a great filmmaker at the end of his career circling back to his origins. Before The Godfather sent him skyrocketing into the pantheon of major directors, Coppola began in the realm of low-budget exploitation cinema, honing his skills first on various softcore productions, and then under the tutelage of B-movie legend Roger Corman.

Twixt, with its cheap look and humble scope, isn’t just proof that Coppola’s capacity to operate modestly and efficiently never diminished—it also finds him revisiting the tonal and thematic territories of one of his earliest directorial efforts, the Corman-produced Dementia 13. In that film, another compact gothic yarn like Twixt, the death of a young girl hangs oppressively over one man’s guilty conscience, plaguing his sleep, driving him away from his loved ones, and infecting everything around him. The two films are very different in execution, of course—Dementia 13 plays out in standard lean and mean slasher fashion, while Coppola plumbs Twixt for deeper psychological aches. Still, the symmetry is conspicuous, and interesting to note.

From its very opening moments, narrated by Tom Waits with his distinctively sinister, guttural growl, nothing about Twixt feels right. Coppola’s roaming camera glides like a spectral presence through the empty, sunlit streets of the anonymous Swann Valley, which seems to exist out of time and out of place. Split dioptres and Dutch angles throw otherwise inconspicuous shots ominously out of kilter. Mihai Mălaimare Jr.’s digital cinematography looks fractionally too glossy, toppling over from clean into uncanny. Dan Deacon’s score, rattling and droning, is thick with anxiety and doom.

There’s immense beauty to be found in the unapologetic sincerity that lies beneath the gauzy, confounding veil.

All of this eerie artifice serves to generate the sense of unreality that’s key to unlocking Twixt as an emotional experience—in the hands of a less stylistically audacious director, the film would probably be close to unwatchable, prosaic from first minute to last.

In isolation, Coppola’s script amounts to an ungainly tangle of woefully thin narrative threads. There’s the overarching small-town murder mystery involving the brutal death of a Jane Doe, with added (and not always welcome) comedic inflections courtesy of eccentric Hall Baltimore superfan, Sheriff Bobby LaGrange (Bruce Dern). Then there are Baltimore’s mundane, utterly enervating daytime struggles, including business conversations with his publisher, and petty arguments over Skype with his hostile wife. And finally, there are Baltimore’s oneiric excursions into an abstract, half-remembered version of the town’s wicked past, in which he converses with a strange, pallid young girl named V (Elle Fanning), and consults the lingering, sagacious spirit of Edgar Allan Poe (Ben Chaplin).

This is where the remarkably elastic direct-to-video digital sheen really shines. Coppola fuses his awkward writing to a visual scheme that’s never anything less than fascinating, and that eventually becomes stealthily poignant, binding the story’s disparate threads into a mesmerising whole. The uniform clarity and lighting of the real-world imagery make Baltimore’s everyday existence look like something out of a soap opera or a Lifetime movie—flimsy, stale, and numbing. Despite the sharpness of the photography, nothing within these frames feels distinct or tangible.

Coppola locks us into Baltimore’s headspace, forcing us to experience the deadening effect of the writer’s overwhelming ennui—human interactions are rendered meaningless, and the only sensation that really registers is his frustration at the tyranny of his latest blank manuscript, with its glaring white pixels and blinking cursor. That this feels as crushing as it does is also a testament to the strength of the often underrated Kilmer, whose performance here, rich with cynicism and self-loathing, represents some of the very best work in his career.

In Baltimore’s dream world, though, textures and feelings begin to fully crystallise. The images here are fluid and expressive: the environments through which Baltimore drifts are blatantly fake, like painted backdrops faintly illuminated by an impossibly starry sky; every other shot, it seems, is embellished either with a layer of fog or sinewy slow-motion; occasional splashes of saturated orange and red are the only outliers in a palette otherwise entirely awash with hoary and bluish tones; and the people who occupy this phantasmagorical space are both luminous and illuminating, literally glowing with white light as they guide Baltimore through the processes of properly grieving and learning to create again.

Once you surrender to Coppola’s vision, once you buy into the mood of the film and synchronise with its slippery wavelengths, Twixt opens up as a stunning rumination on artistic impotence and irrevocable loss. To complain about shoddy CGI, as so many people do when they insist upon labouring through the film with eyes programmed to nitpick, is misguided. Audiences have had their brains poisoned over the years by the widely proliferated notion that all CGI should aim for seamless realism, which is nonsense, of course. Where would the magic in that be?

The transparency of the illusion in a film like Twixt is entirely the point—Baltimore’s conjured visions are in many ways so much more solid, more lucid than his reality. Why shouldn’t the effects stick out? Wielding this technology in such a way that rejects conventional wisdom, Coppola sculpts one of the most poetic images of his entire career—a birds-eye shot of Baltimore and Poe watching the death of Baltimore’s daughter play out on a chromakeyed lake, with a ghostly image of V superimposed upon the water. Traumas past and present, real and dreamed, collapsed into a single image—it’s an astonishing piece of filmmaking.

That Twixt was almost universally loathed upon its initial release, and continues to be widely ignored and rejected, isn’t really that surprising. It’s a thoroughly strange, uneven film, whose idiosyncrasies aren’t always productive. Its emotions, while raw and potent, are frequently undermined by more jarringly silly elements. For many, it can seem unsatisfying, inaccessible, and even laughable. But for those willing to take the plunge, there’s immense beauty to be found in the unapologetic sincerity that lies beneath the gauzy, confounding veil.