Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableEvery month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema, and the filmmaker’s own biography. For January, we look back at the multi-faceted career of Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair, whose textured works expertly thread social, cultural, and narrative borders. Read the rest of our coverage here.

In order to successfully adapt a beloved novel for the screen, a filmmaker must interpret the story in a way that both expresses their unique directorial vision and faithfully renders the original narrative. Mira Nair’s adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s novel The Namesake achieves this challenge beautifully, harmonizing with the novel while shining as a deeply touching classic in its own right, resonating both with audiences who have read and loved the book as well as those who are new to it.

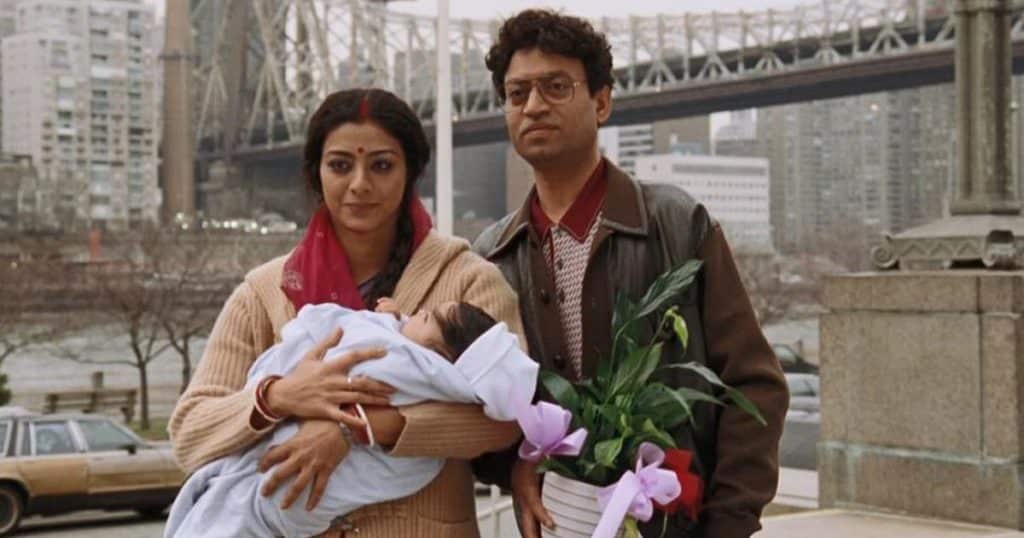

The Namesake is a multigenerational narrative that follows the members of the Ganguli family across two generations and three decades, focusing first on newlyweds Ashoke (the late, great Irrfan Khan) and Ashima (a luminous Tabu) as they travel from Kolkata in the late 1970s to build a new life in New York, and then on their son, Gogol (Kal Penn), whose name and identity ultimately form the core of the narrative as he tries to figure out life as a first-generation American with a name that is neither Indian or American, and connected to his father’s past in a way he will not learn until adulthood.

In a conversation with Lahiri, Nair tells her that she was “absolutely gripped” by the original novel because she “found a great sense of solace in the story” and that in adapting it, she was able to “make a world [she] inhabited [herself].” The first draft of the screenplay, written by Nair’s frequent collaborator Sooni Taraporevala, was written over eleven days — a limited time frame due to Nair’s agent needing to send the script to Cannes for review. After six more drafts, frequently referencing the novel and collaborating, Nair and Taporevala finally landed on the final script, resulting in an extremely thoughtful, detailed adaptation that is faithful to the original text but also brings it to life in new ways.

Unlike the book, which begins with Gogol’s birth in the United States, Nair starts the film earlier, at the precise moment that changes Ashoke’s life forever: a train ride from Kolkata to Jamshedpur in 1963, where he is trying to read a book of short stories by the Russian author Nikolai Gogol, while his seatmate, a gregarious older man, tries to persuade him of the pleasures of moving abroad. Though Ashoke is unconvinced, his seatmate encourages him to pack his things and see the world. “You will never regret it!” he exclaims.

Within seconds, the train derails, killing the older man immediately and leaving Ashoke bedridden for a year. Later in the film, Ashoke finally reveals to an adult Gogol that he was only miraculously found alive because of the torn book pages he had been clutching in his hands and that this is the story behind his namesake.

Even for those who have read the novel and know it’s coming, the accident is shocking to watch, but Nair’s decision to begin the film this way immediately connects us on a visceral level to Ashoke’s psyche and the all the decisions he makes that follow — leaving Kolkata for America and naming his son — the second miracle of his life, in his own words — after the first.

Nair’s scenes are often intimate and quiet, dwelling on both the joy and the melancholy of life as an immigrant and as the child of immigrants — never fully belonging to one place, and never fully knowing one other.

As Gogol grows up in America, grappling with an odd name he hates and openly complains about, Ashoke’s quiet pain lingers in the corners of every frame. Multiple times, he considers telling his young son the truth, but it’s never the right moment. Unlike in the novel, Nair waits for Gogol and Ashoke’s final conversation — though of course neither knows it at the time — for Ashoke to tell his son the truth about his name, adding a bittersweet note to what is already a touching scene.

Throughout the film, Nair’s scenes are often intimate and quiet, dwelling on both the joy and the melancholy of life as an immigrant and as the child of immigrants — never fully belonging to one place, and never fully knowing one other. These understated silent moments are some of the most personal and memorable scenes in The Namesake.

A particularly delightful moment takes place at the beginning of the film, when Ashima, who is about to enter the living room where her prospective in-laws are waiting for her, slips her feet into Ashoke’s American shoes. Taken directly from the novel, it is a wordless, delightful character study. It’s sorrowfully echoed later on, when Gogol goes to Cleveland to empty out the apartment where Ashoke was staying (after he unexpectedly dies of a heart attack) and slips his own feet into his father’s shoes by the entrance.

While much of the dialogue and pacing of The Namesake is taken directly from the pages, Nair also takes small passages from the original novel and teases out little details into fully fleshed-out scenes, turning them into longer threads that connect the Ganguli family members across the generations. Ashima’s father, an artist, is often shown painting at his desk, while Gogol grows up constantly sketching at his desk, and Ashima herself is later shown illustrating elephants on holiday cards.

On a family trip to the Taj Mahal the summer after Gogol’s senior year of high school, Gogol, who is an otherwise awkward and sullen teenager at this point, wanders around in fascination, exploring the grounds, while Ashima and Ashoke converse about how much Shah Jahan must have loved Mumtaz to build such a beautiful tribute to their relationship. Almost on cue, Gogol wanders back towards them and tells them he has fallen in love with architecture and wants to become an architect. “Our family Shah Jahan,” crows Ashima with a pleased smile.

Nair also makes other choices that make the film distinct from the novel — Ashoke in the novel does not smoke and Ashima in the novel is not a talented singer; but the addition of these details feel deliberate and necessary, adding a context that feels distinctly Bengali, along with all the other small nuances that truly make the Gangulis feel like real people— the rapid switches back and forth between Bangla and English, the way Ashima never says Ashoke’s name, and when she arrives in the United States, the haphazard jhal muri she creates out of Rice Krispies, chilli powder, and salted peanuts as one of her first meals.

These mundane details are reflective of the experiences of so many immigrant families. But because they’re so rarely depicted on screen, Nair’s decision to make time to include them feels both personal and welcome. In doing so, she has created and shared a world that she not only inhabited herself, but that many others have as well.

To live as an immigrant is to live in a permanent state of impermanence, where memories are often the only thing that binds families together. Nair understands this, and as a parting shot, she revisits a beautiful moment from Gogol’s childhood, when Ashoke takes him to the edge of the rocky shore to watch the waves crash over the Atlantic Ocean. “Remember this day,” he tells his son. “How long do I have to remember?” he asks. “Remember it always,” Ashoke replies, with a wry smile. “Remember that you and I made this journey, and went together to a place where there was nowhere left to go.”