Initially written off as vapid & glitzy, L.A.‘s a searing indictment of 80s materialism and macho posturing crafted from the era’s shallow pop culture trappings.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

The funny thing about William Friedkin is that if you ask six people what their favorite Friedkin film is, you’ll get six different answers. These hot and cold responses marked Friedkin’s career overall, one that, for all its faults and stumbles, was never predictable or boring. He had no trademark and refused to be pinned down.

This piece was written during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the works being covered here wouldn’t exist.

It must have been easy to be cynical about William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. in 1985. After a blazing hot early 1970s, his critical and popular reputation bottomed out with four straight disappointments. So, it makes sense that someone might think Friedkin’s return to the cop-on-the-edge genre was a purely commercial decision, a hope to rekindle the fire he lit in 1971 with The French Connection. After all, that movie was both a commercial and critical smash.

Perhaps as a result, To Live and Die in L.A. opened to lukewarm reviews and barely turned a profit before quickly being forgotten. That’s a shame because the film is a tense and brutal thriller. It boasts one of the great car chases of all time and a killer soundtrack by Wang Chung. It holds its own as a stand-alone film, but what really makes it sing is how it plays as a B-Side inversion of its more respected cousin.

The French Connection is very 70’s, nihilistic and gritty in a way that feels authentic. Friedkin, who started his career making documentaries, brought a verité sensibility to his adaptation of Robin Moore’s 1969 novel. Relative newcomers Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider added to that sheen as did it unfolding against the early 1970s teetering-on-bankruptcy-“Ford to City: Drop Dead”-Manhattan. Nothing is more real than drugs, piles of garbage, crumbling infrastructure, and just general grossness, right? It made the film feel very important and legitimate. It was one of those movies you walked out of, shaking your head, asking how it all came to this, while also shaking with adrenaline withdrawal from the pulpy tension.

In contrast, To Live in Die in L.A. is as 80s as The French Connection is 70s. To critics of the time, that wasn’t a good thing. While Connection was a serious investigation of the era’s corruption, reviewers decided To Live and Die was pop. It was neon, palm trees, and blazing LA sunsets. Connection had a mournful jazz score. To Live and Die pulsed with new wave MTV energy courtesy of Wang Chung, sleek, trendy, and fun instead of contemplating the moral decay of America.

Some were quick to claim it rejected provoking thought, favoring jacking up its audience on beautiful people doing brutal things in the City of the Angels instead. In other words, just another good time at the movies. The kind of feature perfect for the nation that elected movie star Ronald Reagan president and embraced his whole stupid, decadent decade. But falling for that shallow, glittery sheen ignores To Live and Die in L.A.’s real strength. Inside it beats a dark, angry heart.

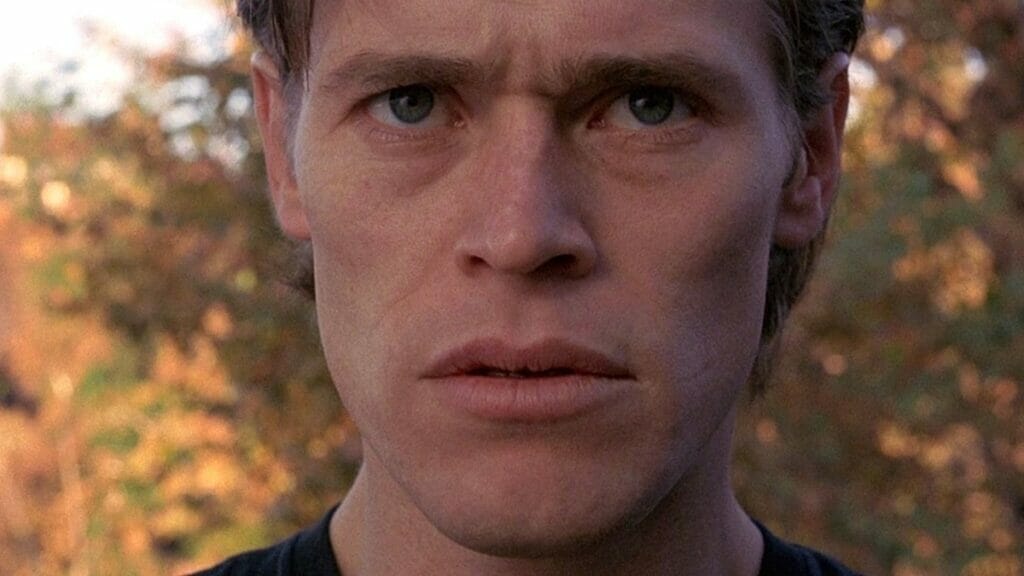

To Live and Die follows the hunt for elite counterfeiter Richard Masters (an incredibly young Willem Dafoe) by fearless secret service agent Richard Chance (William Peterson, as pretty and sculpted as Hackman was scruffy and worn). When Chance’s partner, Jimmy Hart (Michael Greene), dies in a routine investigation, Chance vows to bring the killers to justice. And he’ll stop at nothing to do it, much to the dismay of his new partner, John Vukovich (John Pankow). Chance is a man who lives up to his name. He base jumps, fucks his CI, and takes wild risks on the job. When his superior refuses to requisition a larger-than-usual sum of money to draw Masters into a sting, Chance convinces the reluctant Vukovich to assist him in a scheme to rob a wealthy dealer.

To Live and Die’s thesis is glamour and tough guy posing in 1980s America is a ridiculous farce that gets people killed.

It’s impossible to explore what makes this movie so special without discussing the third act and climax. So anyone who hasn’t seen it and doesn’t want a thirty-eight-year-old movie spoiled should probably stop reading here. Go watch it, it’s great. Then, meet the rest of us back here.

The plot up to that point is pretty rote, with characters and conflicts already cliched back in 1985. But things take a turn. The dealer Chance and Vukovich rob is killed and turns out to be an undercover fed. Suddenly, everyone is looking for the culprits, and unsteady Vukovich is consulting a lawyer about selling his partner out. Things go further sideways during the Masters’ sting, with Chance fatally shot. Finally, when a now radicalized Vukovich finds Masters, he learns the counterfeiter knew it was a sting. He was arranging a suicide by cop, thereby invalidating most of the movie we just saw.

It’s not just money that’s counterfeit in To Live and Die in L.A. The cops, with their stupid macho culture, are too. Chance is every inch the 80s tough guy – he wears tight jeans, a leather jacket, and aviators. Maybe he learned to be a cop by watching Miami Vice. It is Los Angeles in Reagan’s America, after all—the phoniest of the phony. We elected a man famous for dressing up and playing cops and robbers. Is it any wonder the police do the same?

To Live and Die’s thesis is glamour and tough guy posing in 1980s America is a ridiculous farce that gets people killed. The drug wars and cold wars and corporate raiders are all pointless masturbations by a culture in denial, and there’s nothing we can do about it. Vukovich tries to talk sense to Chance in scene after scene but never does. Instead, Chance bullies Vukovich about honor and trust between partners. Then he gets a shotgun to the face. And what does Vukovich do? He takes Chance’s cool guy leather jacket and shades and starts basically cosplaying him. He becomes a counterfeit counterfeit. There are no lessons learned in Reagan’s America, no growth.

The 70s were terrible: Nixon, Vietnam and Cambodia, and Watergate to start. Then, inflation, gas shortages, stagflation, and hostage crises. America was a bloated, corrupt, failing state, and everyone knew it. But it made for great movies that crowded people into theatres and reminded them of how shit everything was. Movies like The French Connection. The thing about the 80’s is they were terrible, too, but large swaths of the culture pretended they weren’t.

So, instead of the cynical hopelessness of Chinatown or The Conversation, we got rah-rah jingoism like Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop—movies designed to make us feel good about culture instead of questioning it. To Live and Die in L.A. tried to subvert that formula with the same tools. It tried to eat its cake and have it too. It was a slam-bang thriller and a moody treatise on how truly lost we were. Sadly, people only seemed to notice that first part. But as years passed and it stuck around, it slowly revealed the layers initially missed to take its rightful place as a classic. It was both a product of its time and ahead of its time. To paraphrase the biggest film of 1985, you could say that those guys weren’t ready for it yet, but their kids loved it.