Gregg Araki revisits and literalizes the apocalypse, with mixed results.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

Coinciding with the release of a new 4K restoration of The Doom Generation, we’ve decided to turn our eyes this Pride Month on Gregg Araki’s oeuvre. In so doing, we hope to shine a light on one of the New Queer Cinema’s boldest, most radical voices.

There’s something to be said for a ramshackle film that delights in itself and doesn’t take anything especially seriously. Unfortunately, what a filmmaker and their fans find fun may read as piffle or drudgery to less dialed-in audiences. Case in point: Kaboom.

Gregg Araki released Kaboom three years after Smiley Face—his funniest film—and six years after Mysterious Skin—his most emotionally honest. By design, the movie is something of a return to the modes of his earlier works. While visually distinct from both that era and its immediate predecessors, Kaboom shares plenty of DNA with Araki’s earlier work. For one, he re-embraces one of his favorite subjects: the end of the world. This time, however, it’s literal.

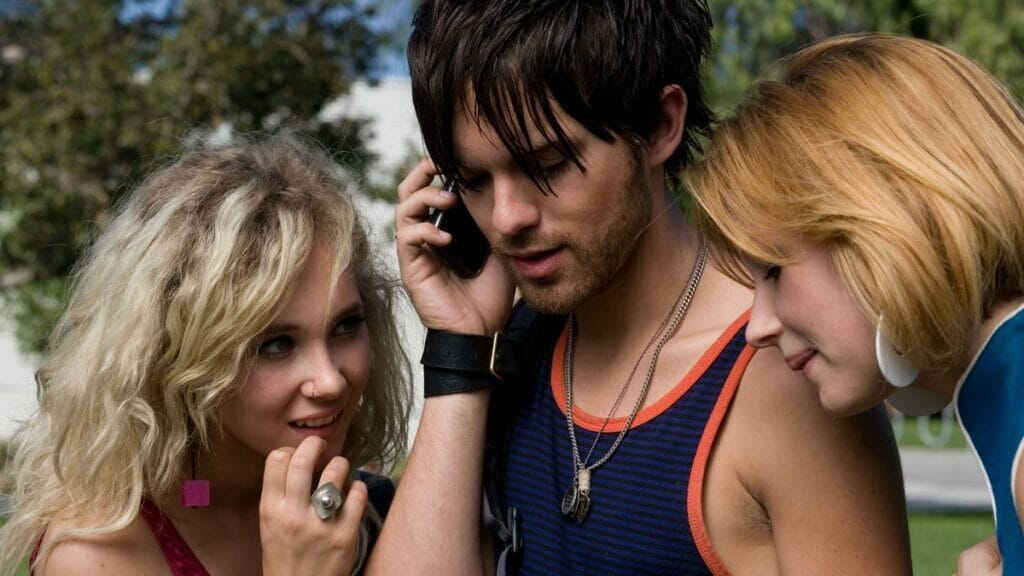

Smith (Thomas Dekker) is on the cusp of his 19th birthday and struggling with a bizarre reoccurring dream involving two women—a redhead and a brunette—he’s never met, a long hallway, a secret door, and a red dumpster. While he finds it unnerving, his best friend Stella (Haley Bennett) is fairly unconcerned. However, when Smith sees the redhead of his dreams at a party and realizes Stella’s new girlfriend is the brunette, it suddenly seems more like prophecy. Heaps of sex, murderers in animal masks, Web 1.0 content, a doomsday cult, twins, and more follow. Everything points toward a genuine day of reckoning, one in which Smith has a special role to play.

In Totally F***ed Up and The Doom Generation—the first two installments of Araki’s “Teen Apocalypse Trilogy”—the Armageddons in question were deeply personal. A world ended for their ensembles, but Earth remained intact. In the documentary-style F***ed, everything comes to an abrupt halt when a character stops the film, severing the viewers from the viewed, effectively erasing their existence. But, of course, the world—ours and theirs—keeps spinning even if the audience can no longer bear witness. Generation concludes on a more visceral and crushing end with the brutal murder of one-third of the feature’s evolving throuple. But a brief epilogue sees the two survivors drive away—their word as a trio ended, but as a duo just beginning.

The trilogy-closing Nowhere, on the other hand, feels closest to Kaboom. There Araki both metaphorically and truly takes the picture’s feet off the Earth. In addition to the personal apocalypse, it’s implied the world doesn’t have long either. Aliens are here, actively abducting people, and the results are fatal. And, if Nowhere’s main characters are any indication, the extraterrestrials are just getting started.

Still, there is a heaviness of event and thought to Nowhere—in line with the two prior “Apocalypse” installments—that’s almost entirely absent from Kaboom. Some of this is arguably good. The lack of sexual assault, for instance, would have felt especially discordant with this movie’s tone. In other ways, however, it leaves Kaboom shallow and thin. It’s a glass of skim milk to the “Teen Apocalypse Trilogy” ’s heavy cream, if you’ll permit a strained metaphor.

[Kaboom‘s] a glass of skim milk to the “Teen Apocalypse Trilogy” ’s heavy cream

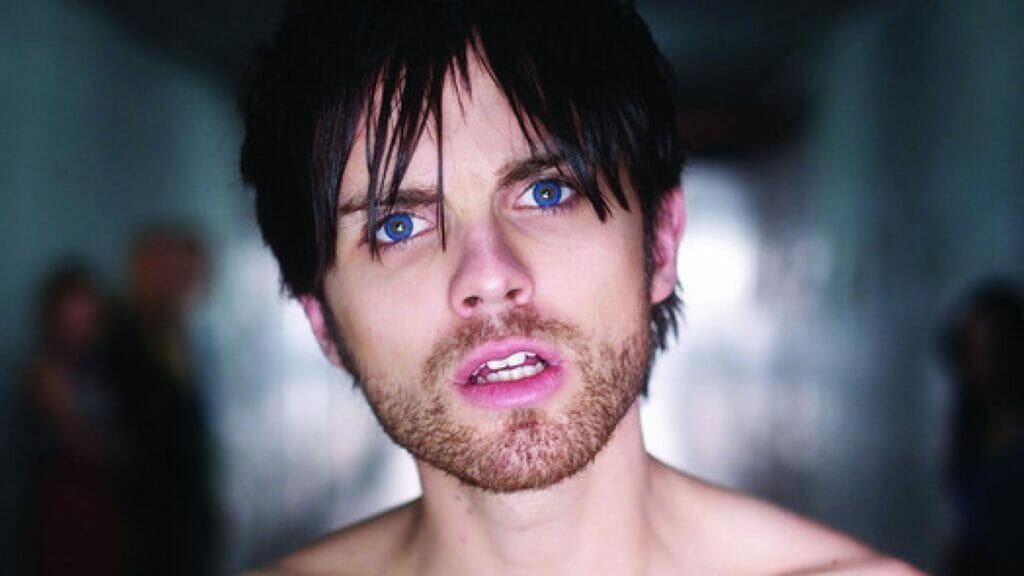

While the feature does evoke some of the same themes as its world-ending older siblings—fluid and queer sexuality, casual drug use, violence, unsupportive biological family structures and their replacement by friends who might as well be family—there’s a flippancy to Araki’s writing and staging that goes farther than any of his other works to date. Even Smiley Face’s stakes feel more immediate and dangerous. Stella’s obsessive, hostile ex Lorelei (Roxane Mesquida), is a literal witch injured by water, making her more of a goof than a threat. Smith’s libido rages but never seems in danger of leading him to a bad end at the hands of bigots. He’s seemingly his own biggest obstacle to sexual and intimate satisfaction and, even then, rarely.

Of course, violence isn’t the only way to give a film stakes, but Kaboom is largely devoid of any other sorts. Everything negative is an inconvenience—and typically a relatively minor one at that. One could argue that having the world end via a character we’ve barely met pressing a large red button is kind of punk rock. Unfortunately, its shrugs at a nuclear holocaust makes it easy for the viewer to similarly yawn at the stakes. The movie can treat the world’s end like an afterthought, but something, anything, needs to have gravity.

Likewise, Dekker doesn’t give the film a strong center. He can occasionally nail a wordless emotional reaction—his face watching his favorite band in concert comes to mind—but the darker material tends to slip away from him. Perhaps there’s an actor who could’ve put this feature on his back and guided the audience to some depth. That doesn’t seem to be the kind of performer Dekker is. He needed a stronger screenplay and ensemble support. Kaboom’s flimsy writing isn’t there ever, stranding the cast—including Araki favorite James Duval in a role that’s never as funny as the film seems to think—without a way to back up Dekker.

That’s not to say Kaboom is devoid of charms. The oversaturated, too-sharp look of the film is an enjoyable aesthetic throwback, for instance. For late 90s adolescents who consumed a steady diet of pop music videos, present company included, it’s a welcome tickle of nostalgia. The clothes and facial hair choices offer a similar kick. But, like that era, all feel a bit disposable now.

The ensemble’s interpersonal relationships also work well. Dekker and Bennett make for good best friends, their constant bickering an ironic shield hiding a deep connection. When the sniping drops, as in the scene where Smith receives Stella’s birthday gift, the results are honest and subtly touching. Juno Temple, as Smith’s friend with benefits London, brings a prickly empathy as well. Other dyads, like Smith and his roommate Thor (Chris Zylka), don’t even attempt depth. However, Zylka’s clueless himbo energy torturing a smitten Dekker by doing everything from always being naked, wrestling his friends, and attempting self-fellatio provide plenty of comedic relief.

Ultimately, Kaboom feels like Araki performing his greatest hits on preschool classroom instruments. The notes are recognizable and Araki seems to be having a grand time. Unfortunately, it isn’t the best way to play the tune. The surprising and unusual reinterpretation of the work Araki did in his “Teen Apocalypse” pictures doesn’t offer further understanding or enjoyment. As a result, it’s good for a laugh, pretty to look at, and little else.