Gregg Araki dissects how identity turns to apathy in his hyper-stylized second part of the Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

Coinciding with the release of a new 4K restoration of The Doom Generation, we’ve decided to turn our eyes this Pride Month on Gregg Araki’s oeuvre. In so doing, we hope to shine a light on one of the New Queer Cinema’s boldest, most radical voices.

“A heterosexual movie by Gregg Araki,” The Doom Generation’s opening credits read. It’s the first of many jokes for Araki’s first film with a crew, shot for $1 million in January of 1994. None of the humor is apathetic, though. It’s like its characters in that way: caustic, yes, even to a fault at points. But the kids at the center of The Doom Generation aren’t apathetic, at least not at the beginning. They’re a conceptual trio of id, ego, and superego filtered through Araki’s lens to serve the narrative, an anti-American mind due to their identities and personal lives. But as they realize their selves individually and as a whole, their heterosexual, monogamous environment relegates them to sameness.

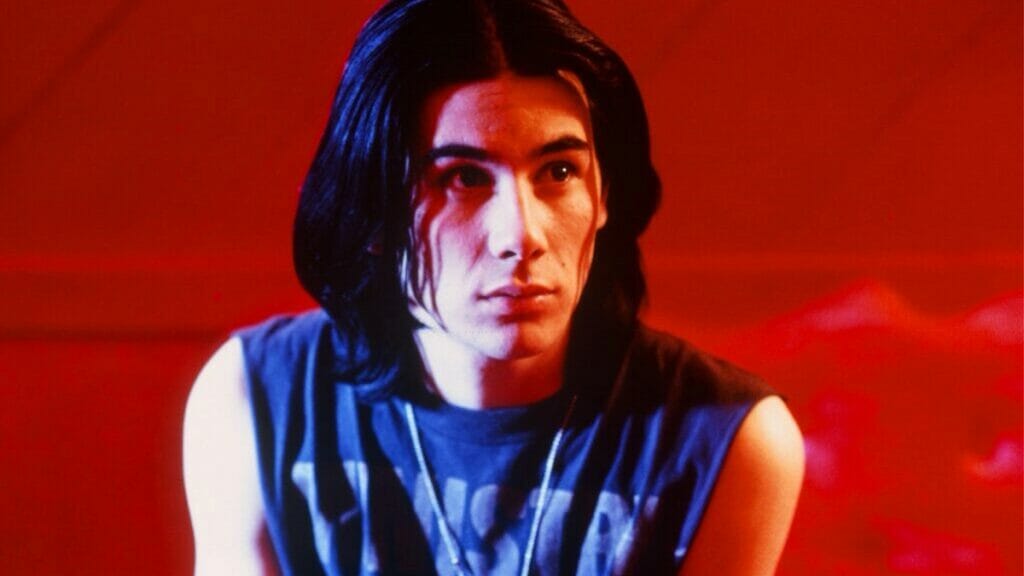

First introduced are Amy Blue (Rose McGowan) and Jordan White (James Duval), a wayward couple on the West Coast. She’s got a forked tongue and a Pierrot le fou hairdo, he a heart of fool’s gold and terminally slacked jaw. Amy’s the ego, a young woman whose annoyance stems from rationality incongruous with the world around her. She’s also the one that, through running gags and side characters’ varying absurdities, endures most of The Doom Generation’s unreality.

On the other hand, he is the superego, or as much as one could be, while fueled on trans fat and slushies. He’s thinking about thinking. He’s idealistic, even. Duval plays him with a sense of discovery and physical freedom. Predisposed toward a stable and almost culturally vanilla relationship with Amy, he’s often trying to quell her anger toward something more socially acceptable. Duval’s also the only one to have a semblance of kinship with their parents and even shows an affinity for cultural ethos in the form of pop culture. But more importantly, he’s about to begin uncovering his queerness.

The two are outsiders, wading through The Doom Generation’s refraction of contemporary culture and mores. The soundtrack, from Nine Inch Nails to Aphex Twin to Slowdive, is wall-to-wall. Celebrity cameos appear through Perry Farrell and Margaret Cho, studded into scenes briefly to prevent playing as full punchlines.

References to religion also abound. Characters refer to locations as heaven and hell, billboards repeatedly foresee the rapture, and Christian iconography exists even in Amy’s car as reappropriated decor. It’s all a muck of mass fetishism, giving life to the film writ large while representing the couple’s banality and imposed restriction. Amy even mentions to Jordan that they’re both virgins.

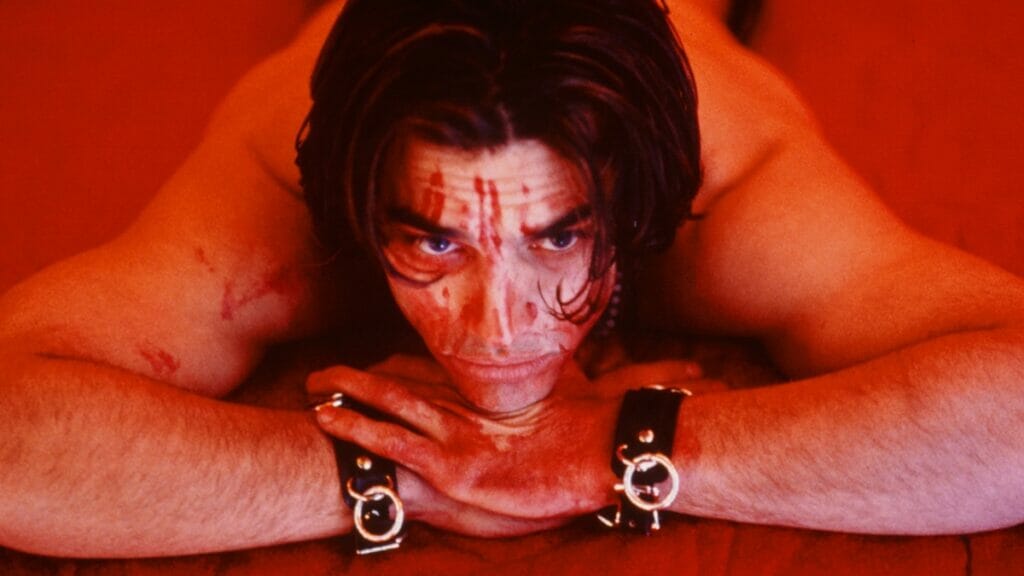

After ditching a club, the two come across Xavier “X” Red (Johnathon Schaech), who falls onto Amy’s windshield during a brawl and is swept up with the couple as they drive away. He’s the movie’s version of an all-American bad boy. He’s also all of America’s ideas of a sexual deviant. He insults Amy with an erotic vulgarity. In response, she tries to control him, kicking him out after she fails to do so.

[The leads are] a conceptual trio of id, ego, and superego filtered through Araki’s lens to serve the narrative.

But X’s interactions with Jordan are more simmering despite their opposing conducts. Eye contact, grazing touches—it’s immediately homoerotic. After X uses Jordan’s shirt to tend to his wounds, Jordan retrieves it, the two bonded by a blood-covered garment at the height of the AIDS crisis. (This also comes soon after Jordan tells Amy he’s “afraid of catching AIDS.”) Here, Jordan preconsciously sees his queerness through X, the former’s identity evolving via the latter. In the story’s regard, the two represent a behavioral, yet not necessarily moral or social, conflict.

X is, in a word, queer, as evidenced by his flirtation with Jordan, but his sheer presence exudes such a counterculture aspect. Yet, while X crashes into Amy and Jordan’s relationship, he doesn’t necessarily interfere with how the two interact. Rather, he’s the id, pure desire and externalized sexuality, his actions driving Amy and Jordan further narratively. With this, Amy is, in accordance with the ego’s role, “driven by the id, confined by the superego, repulsed by reality.” Shortly after the two ditch X, he pops up again at a Kwik-E-Mart when the owner (Dustin Nguyen) pulls a shotgun on Amy. A scuffle ensues, leading X to blow his head off.

And while X’s queerness furthers Amy and Jordan’s pathoses, it unleashes the film’s tone. Here, the shop owner’s severed head continues to scream (and vomits guacamole). In The Doom Generation’s America, the outsider is untethered to reality. Fantasy colors its spurts of rage and chaos, an amoral ejection of the physical and emotional. It’s sudden confusion Amy—and, by proxy, the audience—struggles to rationalize. In a more holistic sense, it’s from this point that X unlocks the film’s aesthetics. Araki and DP Jim Fealy’s gaze careen toward the bold, hyper-stylized impressionism of Jean-Luc Godard, while Thérèse DePrez’s production design becomes stratospheric in construction and contrast.

Now the three are criminals à la Bande à part, staying at a series of ornate motels, some handpainted sets by DePrez and the crew. Amy and Jordan have sex for the first time in the bath. X watches from the hall as the TV news lambasts them as deviants. He masturbates to them, and, in one of many moments originally cut to achieve an R rating, eats his semen. He’s the relationship’s outsider in his queerness, exempt from an instance of heterosexual intimacy, relegated to the narrative role of invader and thematic role of voyeur. Nonetheless, the camera is as attuned to his body as his face. Even alone, his pleasure is much fuller.

X gets the munchies post-orgasm, proposing the three get food. Then begins a running gag of strangers claiming to be Amy’s ex-lover, all of whom swear some sort of vengeance upon her. The first, a drunken drive-thru attendant named Bartholomew (Nicky Katt), follows the three to their motel. Meanwhile, X flirts with Amy. She gives in to his advances, and the two have car sex while Jordan sleeps. Now, Amy’s relationship with Jordan points toward something more open, her own difference from the romantic/sexual norm.

The position of the outsider shifts from X to Jordan, not coincidentally as Bartholomew arrives and declares him a “fucking slimy piece of queerbait” at gunpoint. While Amy distracts Bartholomew, X blows his arm off. On the one hand, it’s another slice of cartoony graphic violence. On the other, it’s an instance of defense against America as it imposes on relationships not closed and straight. The three escape again, but Amy still struggles to apply reason or pragmatism to X and his actions.

She and Jordan discuss him the next day. She’s skeptical of him, but as Jordan continues to realize his queerness, he describes X as “sorta like us. Lost, like he doesn’t fit in.” All the while, the gay infatuation between Jordan and X becomes more overt. Meanwhile, a woman named Brandi (Parker Posey) claims to be Amy’s “eternal love slave.” A Mortal Kombat-interspliced brawl ensues before X intervenes, and the three escape yet again.

Amy gains a begrudging respect for X, which progresses toward attraction. The two have sex again, with Jordan now watching and masturbating before walking into a field of wreckage. But while the role of queer outsider has shifted from X to Jordan since their first motel stop, it doesn’t endanger Amy and Jordan’s relationship. Instead, it’s expanded to polyamory for the three, with Amy at the center. Just in time, she pops on the FBI’s radar. They identify her from the convenience store footage and aim to kill her. In the structure of The Doom Generation, her romantic and sexual choices are triggers for American hegemony to prey on her.

By now, the trio’s relationship further positions Amy, the ego, as the external mediator, via sex, between X and Jordan. She even relays X’s kinks to Jordan later on. When not physically connecting the two, she does in X and Jordan’s conversations. In one scene, X talks to Jordan about threeway sex with an eroticism similar to that in heterosexual, male-oriented porn. Queerness was always external for X and to varying degrees for Jordan, but now such for both. Amy’s romantic and sexual predispositions receive note as well. As such, all three realize and embrace their outsider status in their country’s context. Their interactions become balanced at last, the discussions of past memories alongside the requisite sex talk.

In the structure of The Doom Generation, her romantic and sexual choices are triggers for American hegemony to prey on her.

As a result, the film’s aesthetics don’t revert to a sense of normalcy but progress toward it. They’re banded together now. But like a complement to the surrealist moments before, The Doom Generation treats this tonal shift, this happiness, as ephemera. Suddenly, Amy runs over a dog. X mercy kills it. From now on, her language decomposes from acid spit to apathy. At a record store, another stranger, George (Dewey Weber), doesn’t just proposition her. He simultaneously sees X as queer, harassing him before the three leave and shack up in an abandoned warehouse.

Amy grows quieter, even distant, as the three have sex again. They share their loneliness, the camera growing closer. Araki and Fealy frame them as warmed corpses, Amy wrapped in a plastic poncho with little more than blackness surrounding her and the men’s figures. Jordan asks if X ever wonders about the meaning of life. X says no. Freedom disintegrates toward disinterest. They have a threeway, their collective identity externalized once more.

Then, George appears, revealing himself as a neo-Nazi. He teases Jordan and X with homophobic slurs while his cohorts hold them down, cues the National Anthem, and rapes Amy with a Virgin Mary statuette. Jordan retaliates verbally. Yet his one moment of anger, of queer rage, leads George to castrate him with garden shears. Jordan bleeds out while X is forced to eat his genitals. During a strobing effect akin to the climax of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Amy murders their attackers with the shears.

A hard cut to the next morning finds Amy and X sitting in her car. She’s silent, dissonant behind her sunglasses. He asks if she wants a Dorito and they drive off. After queerness is realized, it turns passive. It is seen, degraded, and destroyed. The external internalized, forced to be repressed. The ego destroyed as the superego is jettisoned, and the id, once a vessel for identity and chaos, sits bereft. It’s a complete death of self-identity. After all, this is no land for openness. It certainly isn’t one for discovery. Amy and X don’t even have time to reckon with what’s happened to them. Not in their heterosexual movie.

“Photographed on location in hell,” the end credits say. It’s another joke, sure, but it’s one born of acquiescence. After all, if the neo-Nazis didn’t get to them, the government probably would have. For all its black comedy and boundless energy, The Doom Generation posits an endpoint not examined enough in independent media: sudden, utter impassiveness. Live in the now and do so in anger, but know that apathy is tomorrow’s only emotion. It’s not just a defense mechanism. It’s a survival tactic, one for a brand new day.