Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableEvery month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema, and the filmmaker’s own biography. In November we’re celebrating Kathryn Bigelow, the first female winner of a Best Director Academy Award, and her fascinating journey from indie genre films to blockbuster political dramas. Read the rest of our coverage here.

Welcome to Officer Megan Turner’s first day. She’s just won over her partner Officer Jeff Travers (Chris Walker) with a joke about she wanted to be a cop because she always wanted to shoot people. As he’s using the bathroom, she happens to notice a robbery in process at the grocery store across the street. When the would-be stick up artist (a young, buff Tom Sizemore) moves his gun on her, Turner empties her service gun center mass, killing him instantly. The two rookie cops fail to properly secure the scene, and one witness, stock trader Eugene Hunt (Ron Silver), leaves with the criminal’s gun in hand.

In the wake of the shooting, Turner ends up suspended for possible excessive force as there seemingly was no gun on the scene. Hunt, meanwhile, has either experienced a psychotic break in the wake of the experience or has found the final piece of a long-developing lust for murder.

Engraving each bullet with Turner’s name, Hunt has begun to randomly gun down his fellow New Yorkers at random. Being so connected to the shootings, Turner ends up pulled off suspension and into Homicide to work with Detective Nick Mann (Clancy Brown). Simultaneously, she begins a romance after a random encounter with a too nice to be true businessman named…oh dear…Eugene Hunt.

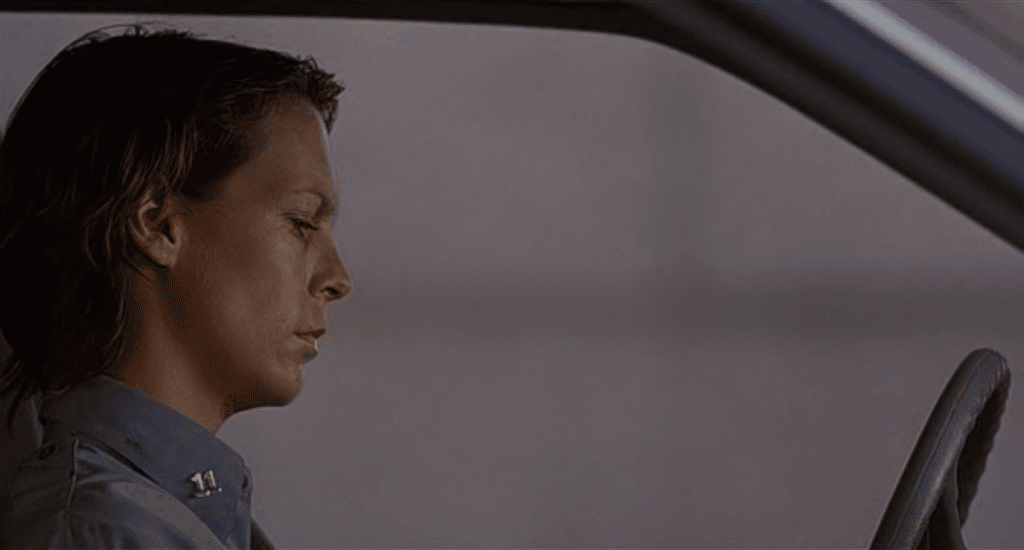

There’s a reading of Blue Steel that operates as a metaphor for Kathryn Bigelow’s own career. Megan Turner (Jamie Lee Curtis) has finished the Police Academy (think of Bigelow’s Loveless as the parallel here) and is about to walk the beat as a full-fledged New York City police officer (comparable to Bigelow’s efforts to breakthrough as a larger budget genre film director) while dealing the sexism that dogs a woman in a largely male world.

Given Bigelow’s long-standing interest in exploring masculinity in film–and the criticism of her for not being as invested in exploring women with the same attention to detail–Steel exists as a thought-provoking counterexample. Turner rarely encounters blatant sexism from her officers or the people around her. An attempted romantic set up (Matt Craven) asks her why she “as a beautiful woman” would ever be a cop is as direct as someone ever gets. Her father Frank (Philip Bosco), already a lifelong domestic abuser, slamming the table and spitting out the phrase “I have a cop for a daughter” is the most venomous.

However, time and again, she encounters silent (but not always subtle) aggressions and microaggressions. While he is quickly won over, her partner’s deeply skeptical of her. When she finds herself suspended for excessive force, the Thin Blue Line fails to snap to her defense. Even on the street, passersby look askance at her whenever she’s in uniform. You can feel the soup she’s steeping in — a world that will let her be a cop, sure, but won’t stop reminding her that she doesn’t belong.

But reading of the film can’t stand up to the plot. It’s an interesting lens to apply, for certain, but as Steel takes shape, examples become far fewer. The theme of “a woman in uniform” rather definitively takes a backseat to a serial killer thriller.

Fans of films like Manhunter, Silence of the Lambs, and even Spider-Man will recognize aspects of those films’ killers in Silver’s Hunt. He speaks with the near-religious zeal of Tom Noonan’s Dolarhyde, seeks to seduce with the same mix of menace and honey-toned flattery as Hopkins’ Hannibal Lecter, and even tries to recruit Turner to his vision of them as gods in a way similar to the deal Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin offers the web-slinger.

The theme of “a woman in uniform” rather definitively takes a backseat to a serial killer thriller.

What’s nice about Blue Steel is that it’s the rare film not to fall in love with its murderer, and thus cede the spotlight to them. Throughout, Turner remains the firm focus and center of the film’s narrative. Hunt is intriguing and gets two juicy showcase moments, but there is never a doubt in whom the film’s most invested.

What’s less than nice is Hunt’s characterization, depicting his mental illness as, “he’s just crazy you see!” He hears voices, rubs his naked body down with a blood-soaked dress, and insists he’s a near deity. It makes the movie feel almost comic book-y (I say as a comic book fan) in its grasp of the character. Moreover, it propagates that ugly stereotype of the mentally ill being inherently violent.

Granted, Silver makes scenes that read silly on the page—arguing with himself while intensely working out, that aforementioned dress scene—legitimately scary and compelling. He makes it believable that Turner could become infatuated with him without noticing how dangerous he’s becoming. But it’s all in service to a fairly flat character with some ugly baggage.

It’s far easier to fully endorse Curtis’s work as Turner. She doesn’t shy away from the less pleasant aspects of the character. She is terse, sarcastic, and quick to anger. Her first act as a cop was almost certainly an overuse of force, even though she was actually right about the robber having a gun and she never once seems bothered by that.

But Turner’s also smart, resilient, and motivated by concern for others. Her love for her best friend Tracy Perez (Elizabeth Peña) feels authentic. The difficulty of her family life comes across as honest and lived in. Curtis sparks dramatic chemistry with everyone on-screen, most notably Silver and Clancy Brown’s cynical and boundary violating detective.

Three films into her filmography, this ability to cultivate both strong individual performances and casts that feel cohesive is becoming a signature of a Bigelow film. As our Filmmaker of the Month reviews over the course of November will show over and over, she has a talent for making movies with strong performances from the top of the call sheet on down. The script, a collaboration with her writer for Near Dark, Eric Red, is thin but everyone invests in making it more than the sum of its parts.

Blue Steel also firmly entrenches us in the “stylish genre” phase of her career. In her vision of New York, it’s a gleaming jewel. She dodges the usual “barely holding on to civilization” look of Manhattan so many have used for a city that looks strikingly beautiful at points. Every building, rain-slicked street, and street light shines bright. That’s all false, though: Like the film’s villain, the sheen hides the ugliness beneath. Bigelow’s New York is Hell, it doesn’t need to look like it to prove the point.

Blue Steel occupies an awkward bit of real estate in Bigelow’s portfolio, as it offers reasons to reject and accept some common criticisms of her work. As noted above, the oft-mentioned centralization of the male experience in her work is contested by a film that actively rejects focusing on the seductive serial killer to stay center on Curtis’s cop. On the other hand, she has also often been called out for making slick, stylish, but ultimately empty films. For my money, that opinion is wrong, but Steel probably comes closest to being that kind of movie.

It also comes just a year before what is the signature film of her first era, Point Break. Much of what people love about Break takes shape here: the use of angle and motion to lend even the quietest scene with a sense of impending action, the use of color and light, and characters that use casual cynicism to cover up their deep emotions and commitments, usually of the unhealthy variety.

Sandwiched between Near Dark and Break, Steel can feel inconsequential. But to do a deep dive into her work and ignore it would be a mistake. So much of Bigelow’s work to come pulls its DNA from this feature. But it’s worth watching as more than an academic exercise; Blue Steel is a stylish, tense thriller with two strong lead performances that more than justify its 100 minutes.