Before he passed away at the age of 46, Philip Seymour Hoffman starred in 52 feature films. Starring roles, character pieces, chameleon work—he left a legacy nearly unmatched in both quality and quantity. Now, with P.S.H. I Love You, Jonah Koslofsky wafts through the cornucopia of the man’s offerings.

Around 7:45, Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) travels towards his death. Has he finally found bliss in the role of another? Caden’s spent decades in pursuit of “the brutal truth,” pouring all he has into a sprawling, endlessly recursive theater piece. Now, his opus lies before him, dilapidated and decayed. As we’ve seen over the painful two hours of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York, his body has fallen into equal, absurd disarray. The rot cannot be mended. All there’s time to do is die.

Sorry, I jumped to the end. It’s 2015 and I’m watching Synecdoche, New York for the first time after my junior year of high school. At a point, I don’t connect with it. Suddenly it’s December 2018 and I’m revisiting Synecdoche, New York with a friend who’s writing a paper on Charlie Kaufman, in my junior year of college. At a point, we find it unbearable.

A few months later, I’m getting coffee with seasoned film critic. He tells me, “There’s a version of the thing you’re writing in your head, and it’s the tightest, clearest expression of what you’re trying to say. But the piece you actually write rarely lives up to that version. What you have to do is make peace with that imperfection, and learn to publish, anyway.”

Today, I am 22 years old. Tomorrow, I will be 45. And the day after, I will die. What am I supposed to do with this week? Pretending I’m anyone else is absurd.

Sorry, I know you didn’t click on this to read about me. You clicked to read about Philip Seymour Hoffman. In one of his first performances ever, Hoffman starred in his high school production of Death of a Salesman in the early ‘80s. In 2008’s Synecdoche, New York, he plays Caden Cotard, a suburban theater director. When we meet him at 7:45, he’s staging an eventually acclaimed production of Death of a Salesman.

“Try to keep in mind that a young person playing Willy Loman thinks he’s only pretending to be at the end of a life full of despair. But the tragedy is we know you, the young actor, will end up in this very place of desolation.” So what should Caden’s actor do? In 2012, Hoffman played Willy Loman in Mike Nichols’ production of Death of a Salesman. Critics thought Hoffman was too young for the part. It was his final stage role.

Sorry, these are just a slew of personal anecdotes and observations, not actual criticism. This time, this week, this third viewing of Synecdoche, I think I got it. Or at least I got closer than I had before. It’s a painful, pathetic movie about our painful, pathetic, elongated moment. It’s about a man who can’t press submit on the imperfect draft, a person as crippled by his own anxiety as the unreasonable circumstances he exists under. It is pure, uncut Charlie Kaufman unleashed on the world thanks to a $20 million budget that it never came close to making back. Oh, I’m at 500 words already? Has a screenwriter ever had a hot-streak like Charlie Kaufman?

In a medium dictated by directors, Kaufman’s scripts were unapologetically his own and always (obviously) about himself. Being John Malkovich burst onto the scene in 1999. He wrote himself in his second collaboration with Spike Jonze, Adaptation, in which Nicolas Cage plays him as “Kaufman” writes the movie you’re watching. Both were nominated in their respective Oscar screenplay categories, and a few years later, Kaufman took home a golden statue for his masterful work on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

A lot of actors (Cage, John Cusack, Jim Carrey) have played Charlie Kaufman. David Thewlis even played puppet Charlie Kaufman in Anomolisa. But no one has ever played Charlie Kaufman like Philip Seymour Hoffman.

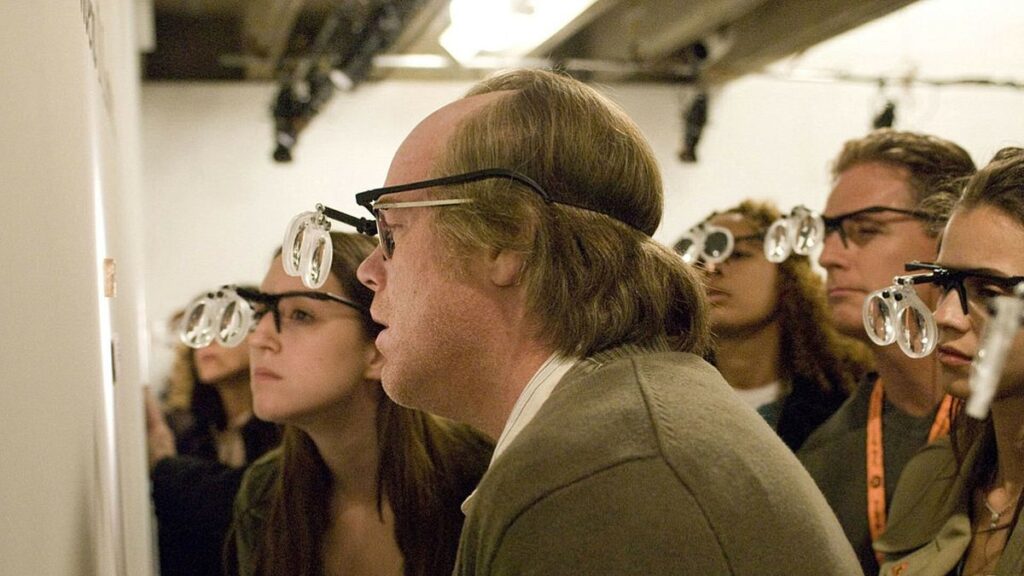

In his surreal, expressionist directorial debut, Kaufman puts Cotard (himself) through the ringer. His protagonist gets gum surgery. He loses the ability to naturally salivate or cry. His pupils stop working. Random spasms pain him, and eventually, his left leg develops a persistent twitch. He’s passed around an endless pool of doctors and specialists. They offer appointments but no cure. Instead, Caden is dying. Slowly.

Hoffman brings this self to life with rigor and vigor. Frankly, Kaufman asks his actor to do a bunch of weird stuff. So Hoffman does all he can to portray every wacky encumbrance his writer/director throws at him, and it all looks more believable than it should. From a purely physical perspective, his performance is a triumph. At the same time, as in Capote, Hoffman’s playing another quiet artist, and he’s also quite convincing as a compulsive neurotic. Few goys have played such a Jewish character so successfully.

Kaufman needed Hoffman to be both naturalistic and bizarre, to find a balance that would translate—and personally express—his ideas and his woes. As the runtime drags on, he slathers Hoffman in old-age make-up. And yet, somehow, in a truly impressive performance, Hoffman locates the truth in these exaggerations. For all 122 minutes, even with all his absurd ailments, Caden Cotard remains recognizable, cohesive, and coherent. He emerges an all-American Gregor Samsa for the 21st century.

There are great performances in which an actor does a lot with a little, be it screen time or depth on the page. Then there are great performances that carry their films. In my Capote piece, I wrote that though he never won another Academy Award, “Hoffman would reach even greater heights before his passing.” Look no further than Synecdoche, New York.

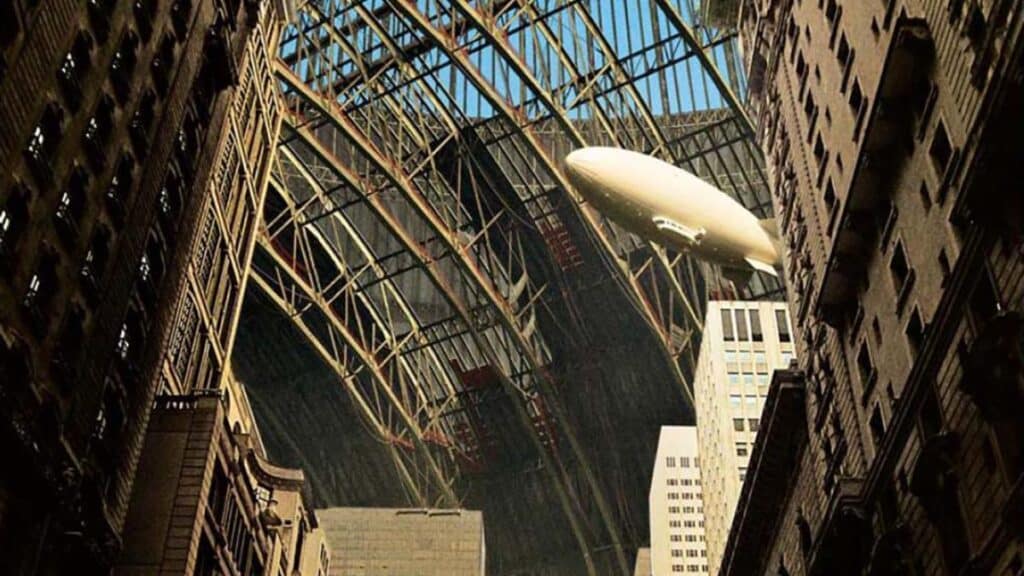

I’m quoting myself, and this piece has become bloated and self-indulgent. After his wife leaves for Germany with his daughter, Caden begins his limitless quest to replicate either, both, or to just fill the void in his life. He begins a series of relationships with women who remind him of his ex. He alienates all of them. He receives a MacArthur Genius Grant, which he uses to fund a theater piece that seeks to replicate day-to-day life down to the last detail. It’s big but not compelling or complete, and it never brings back his estranged spouse. Caden’s surrounded by duplicates. All he can think to do is build more cheap copies.

For all 122 minutes, even with all his absurd ailments, Caden Cotard remains recognizable, cohesive, and coherent. He emerges an all-American Gregor Samsa for the 21st century.

There are all sorts of funny Kaufman touches along the way, but the loneliness always seems to resonate more than the humor. Unlike his prior scripts, it feels like Kaufman has lost control of his machine, daring the viewer to disengage. Around the halfway mark when an extra announces that they’ve been rehearsing for 17 years, Synecdoche’s truly abrasive final hour begins.

Reality—scenes that resemble normal life—become increasingly rare. The movie asks us to care about Caden’s massive, boring project. Perhaps Kaufman’s work is painful by design. Perhaps the unflinching search for “truth” is supposed to come off annoying and grating, the putrid existential vegetables we all need to swallow. Your millage will vary; mine certainly has. Here’s a hot take buried more than a thousand words deep: Maybe Synecdoche would’ve been better as a theater piece. That medium may be more suited to its expressionism; its jokes about its own artifice might’ve landed. Or maybe this cohesion would’ve been too much of an endorsement of Caden’s exercise.

I’ve only seen Synecdoche, New York three times, and I feel like I’m just scratching its surface. That’s so annoying. That’s so exciting. Even its harshest critics should recognize the brilliance of Hoffman’s performance. Even its deepest devotees should see that it is frustrating, agonizing, to watch this movie.

At the end of this tome lies a tomb. Spoilers, I guess, for everybody. Kaufman seems to be saying that the only way out of any of our heads is connection and empathy with other people, even those with radically different experiences. That could be an over simplification, but instead of tweaking this draft to infinity, I’ll end here: Hoffman’s performance, his understanding and expression of Kaufman’s perspective, makes the best proof of his philosophy the film has to offer. Painful as it all is, see it before you die.