We look inside the Gothic influence and drag legacy of Eiko Ishioka’s Oscar-winning costumes for Francis Ford Coppola’s vampiric masterpiece.

When Gary Oldman’s Dracula shows up in modern London at the halfway point of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), it’s clear that he’s aping the look and aesthetics of “Victorianism.” Like the rest of the men, he’s buttoned up in dark colors — but his hat is old-fashioned, his hair is long and down. The colored glasses, dark makeup, and hair all exude an ‘80s metal vibe: think Ozzy in Black Sabbath, Eddie Van Halen, the entire Mötley Crüe. These long-haired types are dangerous men, and cannot be trusted around women.

Clothes maketh the man. Costumes, in Bram Stoker’s Dracula’s case, make the monsters.

In Coppola’s take on the material (as with the subtext of many horror monsters), vampires embody aspects of humanity that the dominant culture finds reprehensible and uncomfortable. By utilizing markers of contemporary subcultures in clothing, specifically anime, rock genres, and drag, Dracula’s costume designer Eiko Ishioka express the social, cultural, and aesthetic danger that the undead represent.

Throughout Dracula, Ishioka consistently uses markers of transgressive identity to indicate otherness and deviance. The opposition to the vampire is the Victorian man, whose typical costume is made up of a dark three-piece suit, white buttoned-up shirt, and a modest hat. They are rarely exposed, always controlled, their uniform acting as a sign of their symbolic dedication to the patriarchal norms that the women and the vampires fight against.

These fashion choices end up affecting vampire couture and goth subculture immediately. Stovepipe hats become the marker of rakish devils across steampunk and vamp scenes. The most obvious place to see this influence is in Neil Jordan’s Interview with a Vampire, when Tom Cruise as Lestat, which helped solidify the hat as a gothic marker. A less direct comparison is Tom Hardy’s character in FX’s Taboo, a man who walks a very thin veil in between life and death. He often wears a stovepipe hat, which is, at this point, a marker of transgressive and deviant behavior we instantly recognise.

Gary Oldman in Dracula

Tom Cruise in Interview with the Vampire

Tom Hardy in Taboo

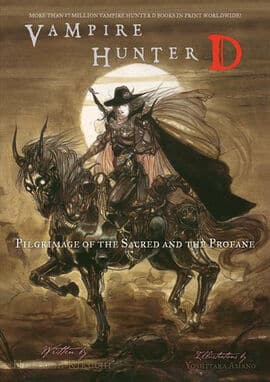

The impression of designs changed the landscape of Victorian Vamp fashion markers, but they were not without references of their own. This bold, modern look, and many others of Dracula’s, are reminiscent of the anime art of Yoshitaka Amano. With wispy lines, bleeding watercolors, and intricate details, Amano’s style is legendary. In the ‘80s he was already an established illustrator, working on ubiquitous franchises like Final Fantasy and Vampire Hunter D.

Like Amano’s D, Dracula is sweeping and Authurian in his romance, a figure seeped in detail. As soon as he meets Mina, he adopts her penchant for leaves and fern-patterning. These ferns were also seen on Elisabeta’s dress. This detail is totally absent from the other men around him, symbolically aligning him and Mina against the patriarchy, a threat to the systems of Victorian control.

Elisabeta’s Dress

Vampire Hunter D

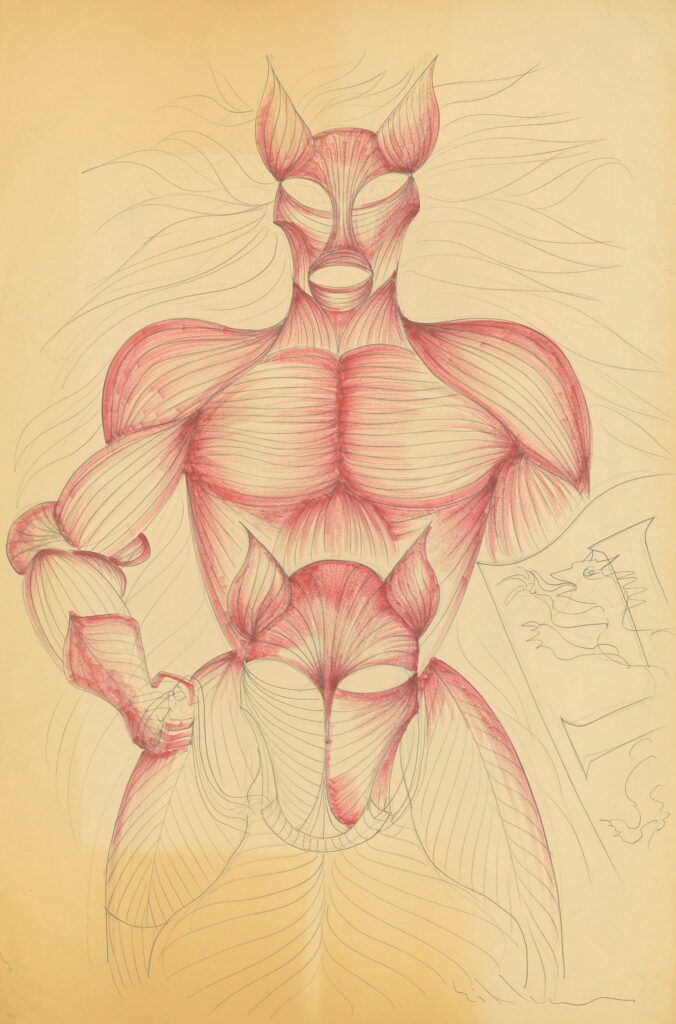

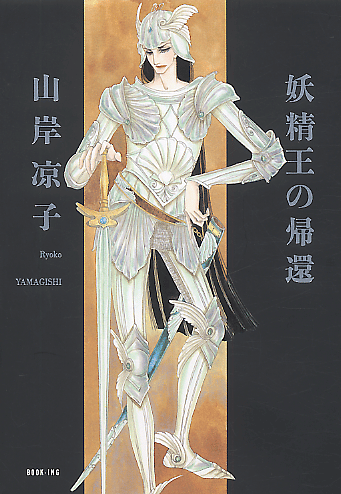

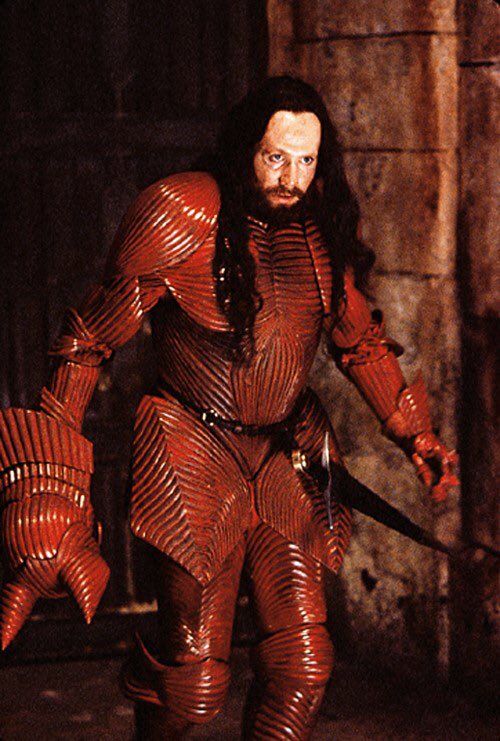

Dracula’s armor remains one of the film’s most iconic looks; inspired by worms and musculature, it also draws on anime tradition to create fantastic and surreal armor. While Japanese samurai had their own style of armor, the Western platemail was constantly reinterpreted by Eastern artists in anime. Shoujo, or girls’ manga, was a style that began in the early twentieth century, and by the ‘60s had undergone a huge revival, full of sweeping romance and queer historical retellings. Armor, in particular, held a huge place within the imagination of Japanese women of this time.

A lovely example of fantasy armor include Ryoko Yamagishi’s Fairy King from her comic Asuka, printed in the mid-’80s. Her work is expressive and revolutionary, and it’s easy to see parallels between her work and the armor, helmets, and fashion created by Ishioka. In the documentary The Costumes Are the Sets, Ishioka stated that she wanted to push the boundaries of fashion and express a “hybrid culture, where East meets West.” This hybridity is a threat. It endangers Victorian sensibilities of what the “orient” is, and where these distinctions lie. In the deliberate mixing of different divergent aesthetics, the armor has already conveyed danger, romance, and the oriental other.

Ishioka’s armor design sketch

Ryoko Yamagishi’s Fairy King

Gary Oldman on set in the armor

The musculature armor has remained a constant touchstone for Dracula adaptations. Ngila Dickson, the costume designer for Dracula Untold (2014) knew they were creating an homage to Ishioka’s design with their dragon-embossed armor for Luke Evans’ Dracula. The horror of the musculature costume also indicates a drag and punk sensibility—you only have to look at Lady Gaga’s 2010 meat dress to see the impact of raw red meat attached to living flesh.

Even earlier than Gaga, Linder Sterling, a punk musician, wore a meat dress in 1987 during a political protest/rock show; before that, in 1982, Jana Sterback created a meat dress for an art show in Canada. All these examples showcase clothing to create a statement that challenges the patriarchy. In Ishioka’s case, it challenges Victorianism.

Ishioka’s execution of this trend is wholly unique while also building on a tradition of challenging tradition. The taboo of having raw meat displayed on your body is as disturbing now as it was then, and the sculptural elements create a disturbing image of a skinned Dracula, drinking damned blood from his own flesh.

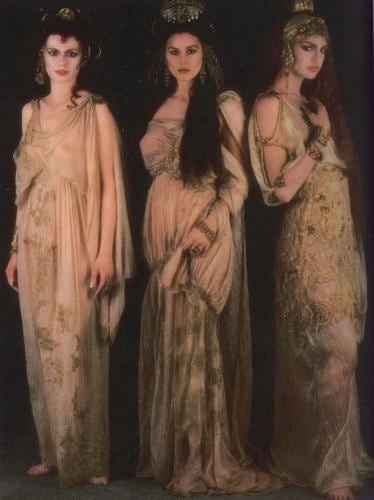

The Brides add in another element of transgressive cultures. With layers of veils and clothing they appear from the bed eager to drink Jonathan Harker’s blood, writhing amid a low, boheme bed and flashing lights. They draw on punk icons like Sousixe Soux, Cyndi Lauper, and Wendy O. Williams; emblems of female sexuality and revolutionary youth.

The veils, jeweled headpieces, and flowing, stola-like gowns were derivative of both Roman, Arabian and Rroma cultures. These markers of otherness appear in later films as well, such as in Van Helsing, where the actresses don skimpy outfits decorated with Egyptian lotus flower motifs and midriff-bearing “Arabian” separates. This “deviant orientalism” is repeated later in the film, when Lucy and Mina examine a copy of the Kama Sutra in private.

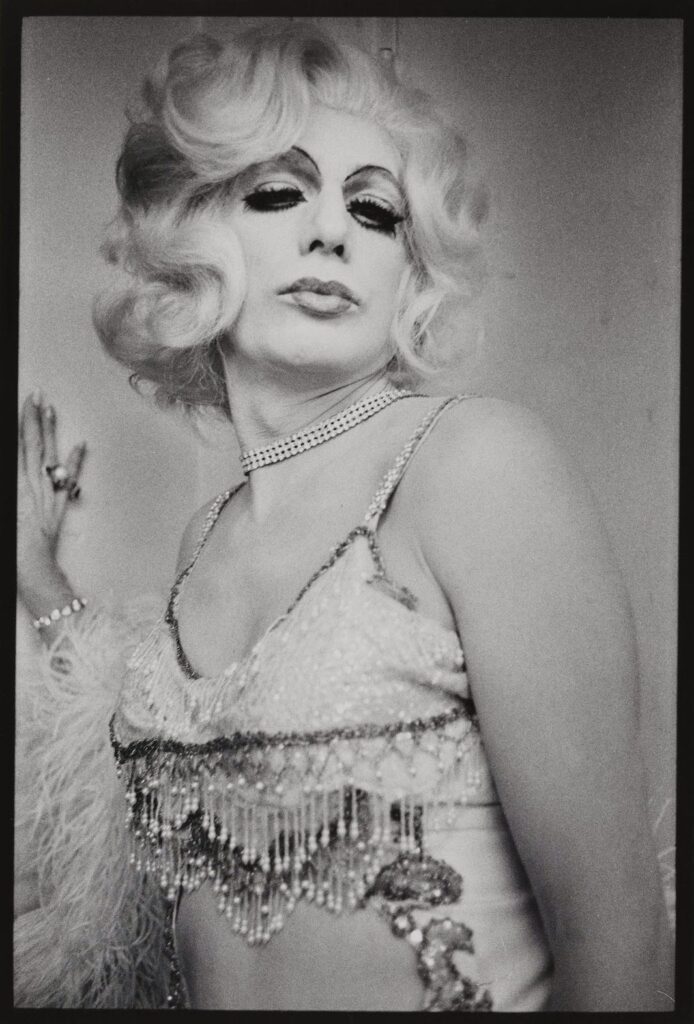

In addition to the orientalism displayed by The Brides, the transgressive nature of their sexualities is further complicated by the way their looks feel very much like drag costumes. Jean Harlow, a drag performer in the 70s, often donned belly dancing two pieces. With over-the-top jewelry, brightly-colored lights, the bizarre walk backwards, the presentation of the brides is very similar to the pageantry of drag balls. Pushing the metaphor is the overt sexuality of the scene, from the very obvious blowjob right down to the men’s arms that hold the lights up in the castle, emphasizing the fetishization of the body.

Coppola’s brides, Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Jean Harlow in the ’70s

Dracula’s brides, Van Helsing (2004)

Though Ishioka infused symbolism into every design choice, Lucy’s wedding/internment gown perfectly encapsulates a perverted Victorian sensibility, mutated by a plurality of transgressive cultures. A major tenet of Issay Miyake, and many Japanese fashion designers, is that freedom comes from obfuscation. For Victorians, everything needed to be buttoned, pinned, and corseted. This gown is the opposite of that, and the embodiment of Lucy’s transformation.

This style of over-the-top headpieces, lace, huge sleeves, a train, and even the makeup, are all elements of drag culture. It’s camp couture to just put a bustle on it and then add a veil and drapery and silk. The extravagance of this costume makes you forget what’s under all of that fabric. This freedom through a refusal to edit is exceptionally offensive to Victorian sensibility. The last decisions that Lucy makes completely on her own are when she designs her gown, this beautiful, over-the-top extravaganza. She might have been buried in her wedding gown, but she looked fabulous.

Lucy’s death dress

Flawless Sabrina, 1970s

Drag culture impacted Ishioka’s designs, either through direct reinterpretation or cultural osmosis. Art exists without boundaries, and as a designer known for crossing boundaries, blurring them, and then reinventing them, Ishioka’s sensibilities align with drag culture. Drag has, at its core, a desire to turn fashion into a value system.

This value system is recognized by those within the culture (in Dracula, vampires and women) while those outside of that culture perceive that fashion to be worthless or even offensive. In order to place current drag camp against the Victorian patriarchy, Ishioka designs Lucy’s snake dress (worn when she’s entertaining three suitors) and Mina’s red flamenco dress (worn at the height of her emotional affair with the prince), both pieces full of markers of seduction and sexuality that Victorian men would not approve of.

The theatricality of these costumes, constrained to sound stages, give the impression of miniature drag balls, little celebrations of drama and camp as each moment of horror is revealed. Each scene is a new opportunity for the costume to steal the show.

Eiko Ishioka conveys danger through avant-garde costuming, using inspirations that push, blur, and chop at the definitions of art through visual associations with countercultural media. Almost every choice she made on Dracula echoed throughout Gothic culture, future Dracula media, and horror films. While this extravagant version of vamp camp seems taken for granted in modern interpretations of the vampire genre, it’s all because Ishioka took a collection of boundary-pushing cultural pastiche and made beautiful, transcendent, surreal wings. She flew so that we could marvel at her work and, like a bat, watch it flit across future films.