Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableThe futuristic religious allegory set to a disco-rock soundtrack turns 40 this week, & must be seen to be believed.

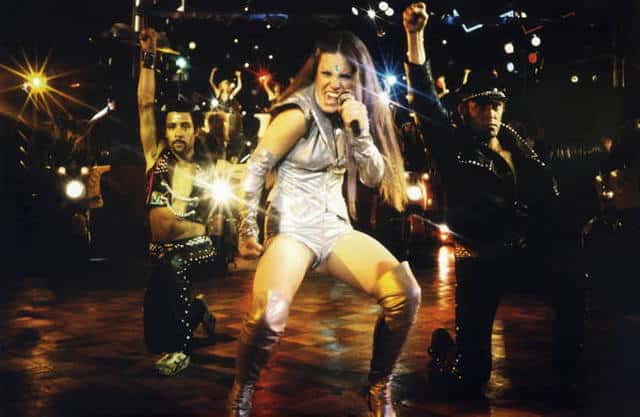

A movie like 1980’s The Apple shouldn’t exist. I’ve seen The Apple with mine own eyes, and I still don’t believe it exists. Part of me believes it’s a shared psychosis, like the young women of Salem, Massachusetts, but instead of witches we saw leather-clad disco dancers and glam rock vampires. Nevertheless, there is evidence that this thing is real, so let’s parse this baffling tribute to the enduring power of love and music (or something or other) together.

You might think, as I initially did, that The Apple was made to cash in on the success of Grease, but it had actually been in the works for more than half a decade. What initially began as a musical take on George Orwell’s 1984 (in Hebrew) was taken over by superproducer Menahem Golan, who, after no less than six (!) rewrites, turned it into an over the top rock opera that resembled almost none of its source material. A timeless tale of good vs. evil, it also purported to be a parody of American excess, a romance, and a cautionary tale about letting success go to one’s head.

You might be thinking “Gena, didn’t they make this movie already?” They sure did, and it was called Phantom of the Paradise. While the two movies are somewhat similar in theme, Phantom is both funny and self-aware, a satire of the music industry written by someone who may have at least been in the same room with someone who was familiar with it. Despite its (perhaps unintentional) camp flair, The Apple plays everything straight, with an earnestness that would be touching if it wasn’t such a hilarious, confounding mess.

Set in the not-too-distant future of 1994 A.D., according to Apple lore the President of the United States, if not every world leader, has been replaced by one man, record company magnate Mr. Boogalow (Vladek Sheybal), who’s apparently the Devil, although no one calls him that. Mr. Boogalow is so powerful that citizens are forced to wear triangle stickers and participate in a mandatory disco-fitness program as part of their allegiance to him. Oh yeah, it’s apparently an allegory for Hitler’s rise to power too, and I don’t want to judge anyone’s art, but unless you’re Mel Brooks (or Bob Fosse) you might want to keep Hitler references in your musicals to a minimum.

A timeless tale of good vs. evil, it also purported to be a parody of American excess, a romance, and a cautionary tale about letting success go to one’s head.

ANYWAY, Mr. Boogalow and his record label, BIM, are so powerful that the Worldvision Song Festival is always rigged in his favor (which makes you wonder why it isn’t just called the BIM Song Festival). Though he steals certain victory in the contest away from them, Mr. Boogalow is taken with the wet noodle folk stylings of innocent young Canadian couple Alphie (George Gilmour) and Bibi (Catherine Mary Stewart). Alphie and Bibi aren’t so much “sheltered” as “raised in a windowless basement with only a guitar and some mice for company,” and thus unable to recognize when they’re in danger, even when Mr. Boogalow and his creepy hangers-on eye them like a plate of hot wings.

The couple isn’t just tempted with money, but sex too, as when Mr. Boogalow’s henchman Dandi (Allan Love), a third-rate Roger Daltrey, tells her he’s a vampire, while wearing a gold spangled jockstrap and presenting her with a giant apple (in case you don’t understand how metaphors work). This actually works, and when we next see Dandi and Bibi, they’re smooching and Bibi is wailing about how much she wants to be wrapped in his arms. Alphie is a bit of a tougher nut to crack, not willing to sign his life away to BIM even after Mr. Boogalow’s henchwoman Pandi (Grace Kennedy) throws herself at him while singing a song called “Coming,” which is exactly what you think it’s about. Repulsed and horrified, Alphie flees, and sets about trying to rescue Bibi before she ends up swapping her soul for success.

Bibi does eventually see the light, and she too flees BIM’s clutches, living with Alphie in a hippie commune led by Mr. Topps (Joss Ackland), who’s apparently God, but no one calls him that either. When Mr. Boogalow and his minions show up at the commune looking to collect on the money Bibi owes for breaking her contract, rather than vanquish Evil, Mr. Topps just raptures all the good souls and they ascend to Heaven in a white Rolls Royce. That’ll uh, learn’em, I guess.

To be fair, when it comes to musicals, plot often ranks a distant third in importance, existing mostly as a gossamer thread leading from one song to the next. Trying to be The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar, and Tommy all at once (with a disco flavor, even though disco was for all intents and purposes dead by the end of 1980), if anything The Apple has too much plot. There’s at least four different stories it’s trying to tell, and they’re all incomprehensible. While Tommy is definitely weird (and might be the only musical with a song sung by and about a child molester), the basic plot is pretty simple: it’s about a deaf, dumb and blind kid who sure plays a mean pinball. It’s impossible to distill what The Apple is supposed to be about in a single sentence. Maybe it’s supposed to be the story of Adam and Eve, but is it, though? It’s possible that it might be trying to say something about America and its obsession with style over substance, but who can say for sure?

The Apple’s vision of the future is lazy and half-formed: the buildings and cars still look like the late 70s (late 70s Berlin, to be exact), while the clothing varies wildly between sequined leotards, leather bondage gear, hazmat suits, Ziggy Stardust and various Monty Python characters. One assumes that the audience is supposed to be deeply invested in what happens to Alphie and Bibi, but they’re personality voids, pawns in an eternal chess game between God and the Devil with no life or motivations of their own. A few gyrating, half-naked dancers and a desk globe sized apple are all it takes for Bibi to give herself over to absolute pleasure, but she just as quickly snaps out of it later. Why? Who knows, we don’t know anything more about these characters by the end of the movie than we did at the beginning, other than they like folk music and apparently really did fall off a turnip truck yesterday.

Pandi and Dandi are clearly supposed to represent danger and the sins of the flesh, but instead they come off as that weird couple who wants to tell you a little too much about their sex lives in the hopes that maybe you’ll ask if you can join in sometime. Dandi’s “seduction” of Bibi takes place in what looks like a dark, smoke filled orgy/nightclub, while shirtless dudes wearing dog masks like the one in The Shining watch, and I don’t know, man, maybe it’s just me but I like my Satans when they’re a little more subtle, bringing that quiet “here I come to steal yo girl” energy, like Viggo Mortensen in The Prophecy. To be fair, “subtlety” is not often something you find in musicals, but it’s not as important when you’re not trying to figure out just what the Mr. Boogalow is supposed to be happening. Watching The Apple is like trying to listen to a child tell the story of the Biblical creation of man, while Solid Gold dancers face off against the cast of Buck Rogers on a porn set.

Despite the title of the article, I don’t want to say unequivocally that The Apple temporarily put a stake in the heart of movie musicals. I will say that after an absolutely embarrassing year that saw Can’t Stop the Music, Xanadu, The Apple, and Neil Diamond’s The Jazz Singer all released within six months of each other (plus Popeye, which is great but still flopped with audiences), Hollywood definitely took a break from musicals for a little while. So if it didn’t place the actual stake there, it certainly helped hammer it in. There would be no major musical released again until 1982 with John Huston’s take on Annie, which was a modest box office success and received lukewarm at best reviews.

Though they were once the lifeblood of the entertainment industry in the 1930s and 40s, musicals of the 80s remained mostly reserved to cartoons, or oddities like Julien Temple’s Absolute Beginners. In the 90s live-action musicals were almost non-existent, and then came roaring back in the 00s, with elaborate cinematic productions of Chicago, Les Miserables, and of course, the instant classic Cats. Only the surprise hit The Greatest Showman was an original story, rather than based on a known property. It didn’t get more “original” than The Apple. It was so original that even the filmmakers couldn’t tell you what it was about.