Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableAlex Cox’s Sid Vicious/Nancy Spungen biopic is harrowing, but his unsentimental eye and the picture’s tremendous performances are indelible.

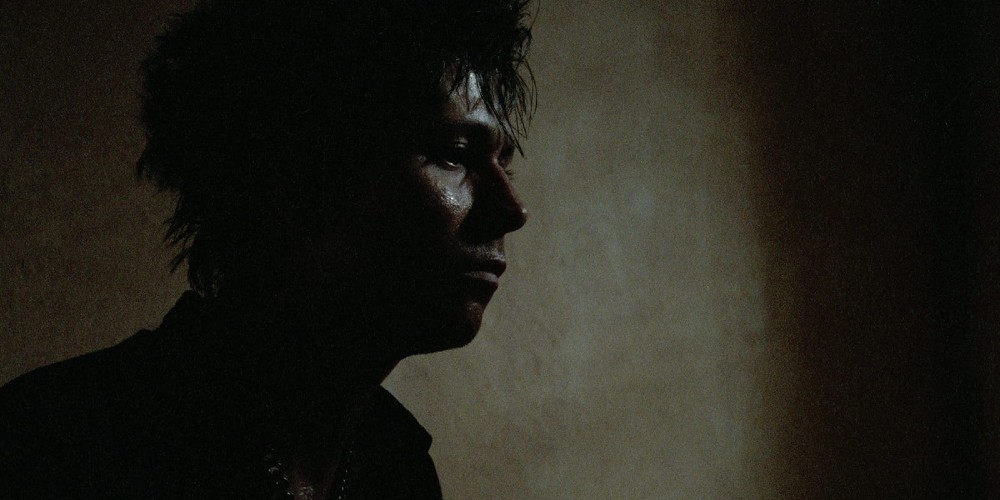

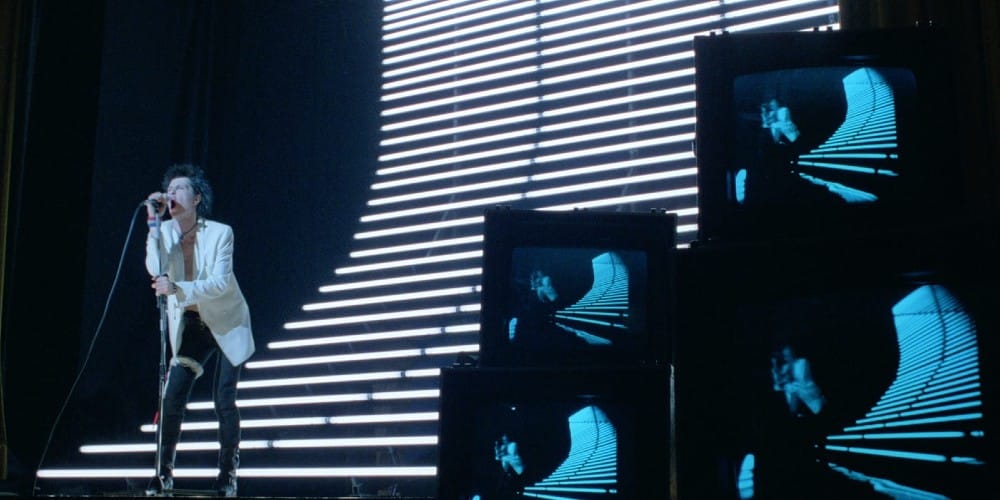

By most accounts, Alex Cox’s Sid & Nancy is not a particularly accurate depiction of the relationship between Sid Vicious, the most notorious member of the Sex Pistols, and Nancy Spungen, the American with whom he had a relationship that began in a state of anarchy, was sealed in a haze of drugs and ended with him allegedly stabbing her to death in a bathroom only a few months before he would himself die of a heroin overdose at the age of 21.

Considering the sordidness surrounding their brief lives and untimely deaths, Sid & Nancy’s deviation from realityis probably a relief. A truly spot-on representation would have probably been too grim and depressing for all but the masochistic of audiences.

And yet it was perhaps inevitable that someone would try to turn their story into a movie. In the hands of some, their story might have been romanticized and warped into a Romeo and Juliet riff with better haircuts. That it is not the take that Cox chose to present. Instead, Repo Man’s director opts for a tougher, stranger, harder-hitting take. He does not present Vicious and Spungen as two misfit spirits who found each other in a world that simply did not understand them. Yet Cox’s approach yielded a film that was both tragic and shockingly romantic.

Sid & Nancy subverts audience expectations right from the start by opening on the lifeless body of Nancy (Chloe Webb) being wheeled out of New York’s Hotel Chelsea on a stretcher while Sid (Gary Oldman) is taken into police custody, too shellshocked to describe what happened to his interrogators.

Cox then jumps back in time to about a year earlier, when Sid had become the face of punk rock through his membership in the Sex Pistols, and he and friend/bandmate Johnny Rotten (Andrew Schofield) are introduced to Nancy, an American groupie who has come to England to sleep with the band. Sid initially rejects her but changes his mind when he sees her being dismissed by his fellow punks. The two soon begin a romance cemented by their shared infatuation with heroin, to which she introduces him.

Rather than trade in the overt romanticization of its subject, Sid & Nancy instead offers a perceptive observation of Vicious and Spungen as people.

The romance drives a wedge between Sid and the other Pistols and when the group departs for a brief tour of America, and Nancy is left behind in London. After barely a month on the road, the group self-destructs in a haze of booze, drugs, and lunacy. Sid, ignoring the warnings of several friends, returns to Nancy. She decides to help him capitalize on his infamy by turning him into a solo artist, but their attempts fizzle.

When Nancy brings Sid home to meet her family in Philadelphia, it goes expectedly poorly. Their relationship spirals further, to the point that they make a suicide pact, and ultimately decide on a stay at the Chelsea—the same stay that will end in Nancy’s death.

Alex Cox debuted with Repo Man in 1984. While not a hit in theaters, it proved big on video and announced him as a talent to watch. That said, it’s hard to imagine a film less likely to capitalize on the heat Repo Man generated than the relentlessly grim and bleak (though not without moments of dark humor) Sid & Nancy, a drama suffused with agony and death.

It wasn’t some long-gestating passion project on Cox’s part either—in interviews, he’s often dismissed Sid as a sellout to the punk ideal who died a pointless death. Cox has suggested that one of the reasons he opted to make the film was to avoid the kind of romanticized depiction of Vicious that might have solidified him in the public consciousness as something he wasn’t.

Whatever one may think of the film as a whole—and some of Sid’s contemporaries, most notably John Lydon, flat-out hated it—Cox and co-writer Abbe Wool succeeded in that regard. Rather than trade in the overt romanticization of its subject, Sid & Nancy instead offers a perceptive observation of Vicious and Spungen as people. They may have appalled most who encountered them, but they fit in with each other.

Any chance Sid and Nancy might have had was undercut by Sid’s quick rise to stardom—one sparked more by sheer outrage than talent—and the allure of the drugs that consumed them. The duo was nearly catatonic on the best of days and, as the movie tells it, there were very few of those. In one of the picture’s best scenes, the zoned-out couple visits a methadone clinic where they are taken to task by a caseworker (Cox regular Sy Richardson) who chastises them for reducing themselves to barely sentient zombies instead of using their fame to sell a form of “healthy anarchism.”

Despite its bleakness, the film works as a powerful and at times legitimately romantic drama, in large part thanks to its stunning performances. This was only Oldman’s second major film role, and arguably he has yet to top it. His Sid is closer to a force of self-destructive nature than an actual person. And in what would be her film debut, Webb more than holds her own as Nancy, a high wire act of a performance that requires her to come across as deeply repellent while simultaneously allowing viewers to recognize what Sid might have seen in her in the first place.

When Sid & Nancy opened in 1986, it received rave reviews from some but proved to be too much of a downer for even the arthouse crowd to embrace. Even with Oldman and Webb’s tremendous work, they and the film were, overlooked at Oscar time. Like Repo Man, it would find an audience on home video and would eventually go on to become a cult classic. Oldman’s career would launch into overdrive as the result of his performance and Webb would become a familiar face in film and television as well over the years.

As for Cox, the heat he garnered with Sid & Nancy would all but dissipate less than a year later thanks to the back-to-back failures of his bizarre crime comedy/spaghetti western homage Straight to Hell and Walker, a corrosive indictment of America’s long history of meddling in Central America that he somehow convinced a major studio to finance, no doubt to their everlasting regret.

Biopics of musicians are common today, but they’re frequently safe, non-confrontational works that seem to exist only to garner Oscar nominations for the actors playing the stars and revitalize music sales. Sid & Nancy denies those stagnant formulas in the same way that punk music rejected the conventions of rock music at the time, and the results are as electrifying today as they were in 1986.