Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableAbby McEnany’s autobiographical Showtime series is a wry, funny, deeply queer breath of fresh air.

We must be reaching a change in how we create and critique queer representation in media. Showtime’s latest additions The L Word: Generation Q and Work in Progress represent two illuminating turns in conversation: The L Word reboot reflects on its own legacy as a landmark series for queer lives on television and tries to build from it. Work in Progress takes a heartfelt new perspective that pushes the conversation of representation in very exciting ways. It boldly confronts representation in a bar — before promptly fainting.

Work in Progress follows Chicago comedian Abby McEnany, playing a version of herself, as she labors through queer life, trying to make it better (one almond at a time) before she kills herself. With buttery, wry humor, the series digs at the loneliness and isolation one can feel as a queer person under capitalism, where one is stigmatized for an array of things that make daily life drudgery.

There’s a really warm heart in this bleak midwinter debut. It’s about coming out of the loneliness of queerness, middle age, and the Midwest, chiefly through the twin pillars of hope and community. I don’t think it will be a smooth or linear road to wellness for Abby, but the first half of the season made available for critics lays out an earnest effort to build trust in the storytellers (and the community of characters) for when the rough times eventually come.

Abby’s family is lovely. Her best friend Campbell (the delightful Celeste Pechous) is a great compliment to Abby’s immovability. From the beginning, the relationships between characters from the onset feel authentic and matured, like we’ve entered a work in progress that’s already in progress.

But once Abby meets Chris (Theo Germaine, The Politician), their world begins to open up and we are exposed to the dazzling array of queer experiences. As Chris and Abby start a relationship, we see cis and trans people from two different generations getting to know each other, figuring out each other’s vocabulary. There’s so much giddy chemistry between the two that nothing feels forced. If/when this sensible shoe drops, it will be heartbreaking.

In this Work in Progress shares another thematic echo with The L Word: Generation Q; both are stories about intergenerational love and queer discourse. Work in Progress shows an honest attempt at understanding, loving, and fucking a different generation. (In the darkest sex scene I’ve seen on Showtime, I might add, in that it’s literally dark. You can’t see a thing!)

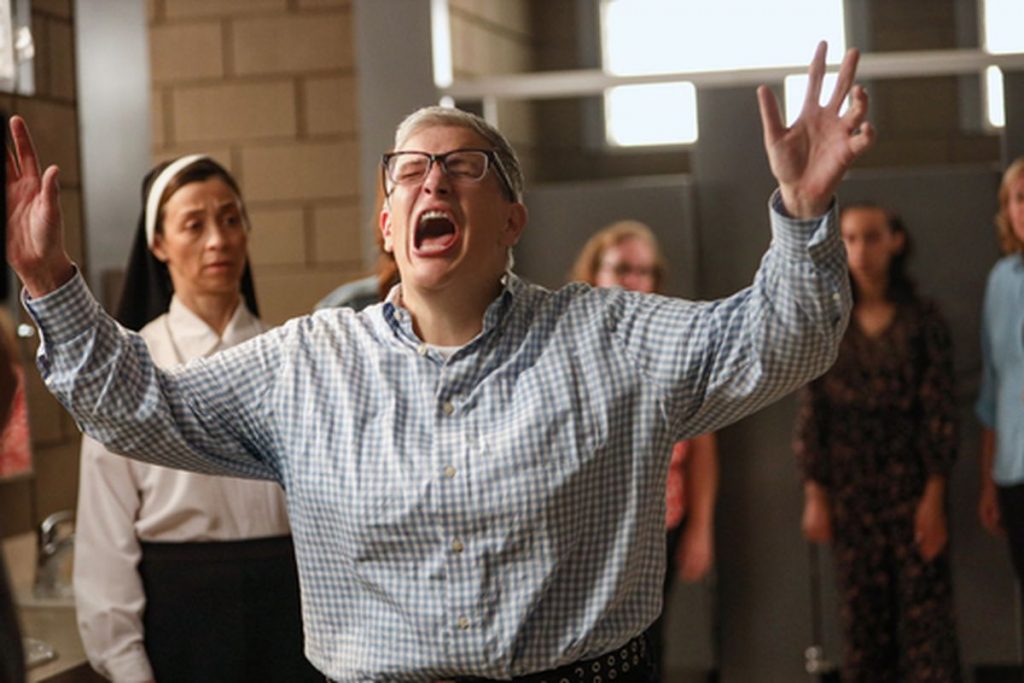

Each episode uses every one of its 30 minutes to incisively explore issues or themes that affect queer life. Of particular focus is the way why gender non-conforming bodies negotiate public and private life. It knows the supreme discomfort of a Lyft Share. It’s been through the shame of having your gender interrogated in a bathroom. It understands that these material circumstances have psychological (and often physiological) repercussions. Yet the result of all this threat and menace on the periphery is that Work in Progress finds space to laugh and grow.

Work in Progress shows an honest attempt at understanding, loving, and fucking a different generation.

Here, however, is where Work in Progress will need to be more mindful as it continues. Often, the politicized dialogue can shift from a criticism of a social construct or issue to a didacticism that takes us out of the scene. Conversations quickly turn into lectures that obstruct the flow of the scene and dulls the point.

This show is going to be watched mostly by queers and their allies, people who probably share the same lexicon and moral code as the characters, so such lessons are superfluous. Work in Progress does enough great things on its own without needing to instruct its viewers. We don’t need to make converts with every outing.

The most revelatory thing about the series is how it uses its meta-ness to directly address representation. Abby encounters actress Julia Sweeney (playing herself) at a bar and works up the gumption to confront her about her notorious SNL character, Pat, the “gender confusing” person whose punchline was that their weight and style made their gender indiscernible.

Abby gets to address a tangible example of a harmful representation that has haunted the fat queer and trans communities and it also gives Sweeney space to admit fault, apologize, and make amends. Other guest stars appear as well, notably other artists who’ve used queerness and poorly-aged portrayals, giving them a chance to reckon with the impact of those contributions.

These moments when we are given time to reflect on where representation has been, show us where representation is going. Instead of harmful queer representation made from outside the community, we are given a show made by queer community about and for the queer community. That it confronts the real past is really intelligent TV-making because it demonstrates why representation is important. Through Abby, we see the lived repercussions of mismanaged characters. Yet, Work in Progress gives the queer community a hopeful chance to correct the course now that we are producing our own stories.

Work in Progress may be as imperfect as the title implies, but at least it has a clear mission statement about interrogating the intricate, multi-faceted lives of multiple generations of queer people. If it continues to believe in that purpose, it will find its footing and make a show that says something larger than itself. Right now, Abby and the show don’t know how they’re going to get to where they want to go, but they’re exuberant about the journey. Its essential they hold onto that joy; losing it would mean they’ve run out of almonds, and an ambitiously queer series will be dead far too soon.

Work in Progress airs Sundays back-to-back with The L Word: Generation Q on Showtime.