Overlooked by most audiences upon release, Smiley Face puts a much-needed feminine spin on the stoner hangout comedy.

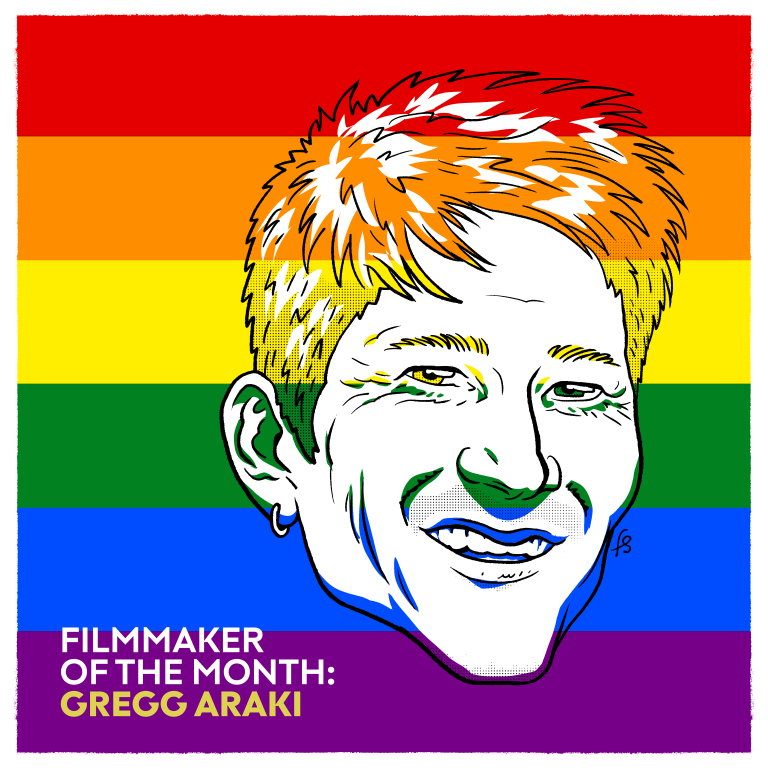

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

Coinciding with the release of a new 4K restoration of The Doom Generation, we’ve decided to turn our eyes this Pride Month on Gregg Araki’s oeuvre. In so doing, we hope to shine a light on one of the New Queer Cinema’s boldest, most radical voices.

As far back as the propagandistic days of 1936’s Reefer Madness, the onscreen adventures of those hooked on marijuana have long been a man’s domain. This boys club of bud appreciation has provided men a cinematic space to roll a joint, puff away, and ruminate on the inner machinations of, primarily cis-hetero masculinity; girl trouble, career stagnation, societal infantilization, and the general inadequacy of one’s day-to-day existence. That puff of reefer is enough to lower the mind’s defenses and reach an emotional cavalcade that unlocks heartbreak and humor in equal measure. Thus, the “stoner comedy” was born.

The genre has seen various highs (pun very much intended) and lows, most notably seeing immense financial success with Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong’s Up in Smoke, followed by a franchise of numerous “Cheech & Chong” adventures. The genre hit its stride in the ‘90s and 2000s, perhaps as a filmmaking backlash to the nascent D.A.R.E. initiative, resulting in Dude, Where’s My Car?, Dazed and Confused, and even television’s “That ‘70s Show” using 1970’s nostalgia to ride the wave of the trend.

The stoner comedy has thankfully not been a completely whitewashed zone, with the Friday franchise, the Harold & Kumar films, and the Meth & Red classic How High providing potent social commentary alongside idiotic humor. Behind the scenes, directors like Tamra Davis (Half Baked) and Amy Heckerling (Fast Times at Ridgemont High) have provided broader filmmaking perspectives for the genre, but the fact does remain; the stoner comedy, by and large, has been an arena for stories about men and their various escapades.

Enter Gregg Araki, New Queer Cinema icon, currently in the midst of a grand reevaluation – an “Araki-ssance,” if you will – brought on by brand new restorations of his ‘90’s Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy (Totally F***ed Up, The Doom Generation, Nowhere), rightfully shining a light on a director whose work was perhaps ahead of its time as a stylistic portrait of youthful, angst-filled queer reckoning.

But in this current reclamation era for Araki, there’s good reason to expand our reappraisal of a career too often left in the margins of film history beyond just the boundary-pushing, in-your-face dark comedic stylings of his ‘90s era. That same voice for youthful button-pressing found itself gleefully applied to the world of the stoner comedy in 2007’s Smiley Face, which finally provided something that the genre had been lacking for decades on end: a female protagonist.

As hyperbolic as it may come off, it’s difficult to walk away from Smiley Face and not think that Anna Faris – playing the film’s perpetually stoned protagonist Jane F. – is giving one of the most committed comic performances of 21st century cinema. Writing off her comedic acrobatics as simply foolish child’s play seems myopic; her face contorting between wildly vacillating emotions, her eyes bulging out of her skull when hiding in the bathroom, her jaw drooping into nightmarish angles. Her commitment to the play demanded of the film only hammers home the terror of the trip she’s on.

Araki has gone on record saying that he made Smiley Face as an intentional companion piece to his prior film, the much darker exploration of childhood trauma that is his masterful Mysterious Skin. There’s certainly some truth to this; Araki’s earlier output of apocalyptic queer cinema in the ‘90s sat perfectly calibrated between stories of pain and violence alongside despair steeped in a dark, anarchic humor, always with a sickening grin on their face. For his duology of ‘00s entries, Araki’s works are firmly planted in their respective genres, but are each singularly Araki-esque; the fanciful camerawork, put-upon performance styles, and bright and poppy aesthetics are employed to means both despairing and delirious, and Smiley Face weaponizes the mania of Araki’s filmmaking talents to delightful ends.

But to answer the self-prescribed thesis here; what does a stoner comedy look like with a woman at the helm? To be honest, pretty in step with the genre as a whole, and just proves the complete incompetence of constricting this genre to a single gendered experience for so many years. Jane is consistently buffoonish along her journey, and has bouts of horniness along the way too. The horror of navigating the world while experiencing a disastrous edibles trip is, for many a stoner out there, a universal experience, and Jane’s journey is less about providing some Girl-Bossification of the stoner comedy and more so just a prime comedic vehicle for Faris’ many talents.

It’s difficult to walk away from Smiley Face and not think that Anna Faris is giving one of the most committed comic performances of 21st century cinema.

To recount the actual plot of Smiley Face seems futile at this point, a film whose plot mechanics of overdue debts, forgotten appointments, character betrayals, and wild goose chases somehow leads us from Jane devouring an entire platter of weed cupcakes to her sitting atop a ferris wheel clutching a first edition copy of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto. To aid in this inanity, Araki litters the film with an array of comedians both well-known and underground by this point in the mid-2000’s, with the likes of John Krasinski, Adam Brody, Jane Lynch, John Cho, Brian Posehn, Jim Rash, Ben Falcone, and Michael Hitchcock all providing comedic texture to this sunny, absurd portrayal of Los Angeles.

Jane’s journey carries with it an almost cartoonish quality, her perpetual sense of weed-induced delirium providing Araki a prime array of cinematic opportunities to accentuate her state of mind, including frequent zooms and close-ups, characters defiantly addressing the camera head-on, even the frame itself irising in and out, and shattering like glass. A moment as seemingly mundane as Jane trying to back her car out of a parking garage leads to a freakout moment of garage pillars navigating the frame like bumper cars before the literal devil scares Jane enough to roll out of her car in a moment of physical comedy that would make Buster Keaton guffaw in his grave.

The widespread proliferation of marijuana legalization in the U.S. has slowed the roll of the stoner comedy, a taboo pastime now gaining social acceptance and thus seeming less hip as fodder for lackadaisical entertainment. After another moment of cultural dominance with 2008’s Pineapple Express, the genre has generally slowed down from there, leaving the moment for the passing of Smiley Face’s baton of female stoner ludicrousness to languish for the time being. The promising recent news of a Kristen Stewart-led stoner-girl comedy provides hope that the genre can continue on, but in a way that feels in step with the rest of his career – whether intended or otherwise – Araki brought his talents to a genre typically built upon machismo and broke it apart to create what might just be his comedic zenith.