KinoKultur is a thematic exploration of the queer, camp, weird, and radical releases Kino Lorber has to offer.

It’s no secret that the gothic genre has a thing about houses. The best of them have elegantly laid blueprints, constructed to take audiences and characters on a tour of confusion, despair, and desperation. But not all architecture’s made equal.

Some, such as the four new releases from Kino Lorber considered here, have quite a clumsy configuration. Yet, while they may be an unsure mix of structures and patterns, they show bold attempts at originality. Admittedly, they are not sturdy structures, but looking at their floor plans can teach us plenty about narrative design, structure, and the supernatural.

We begin our tour with 1933’s The Secret of the Blue Room. This black and white mystery thriller, directed by Kurt Neuman (The Fly, 1958), concerns a mysterious blue room, locked ever since a series of suspicious deaths happened within its walls. On the eve of Irene von Helldorf’s 21st birthday, she (Gloria Stewart, Titanic) along with her three suitors Tommy (William Janney), Frank (Onslow Stevens), and Walter (Paul Lukas), gather to celebrate. In a fit of jealous rivalry, Tommy wagers he could last one night in The Blue Room. Suspicion and suspense begin to rise as the men seem to fall prey to the cursed chamber one by one.

It’s a curious little picture that’s more concerned with tenor than clarity. The suspense is elegantly layered as The Blue Room becomes more and more of a puzzle. Yet, by the end, I remain unconvinced we have all the pieces to discern the room’s fatal power. The room itself remains unexplained. Worse, the film fails to make it clear that the horrors of The Blue Room stay a secret as a matter of design.

While the plot may not be completely cohesive, The Secret of the Blue Room remains fascinating to watch for how it captures the interaction of Pre-Code and Hays Code era moralities. The film opens on Irene’s birthday when she’s becoming “free, white, and twenty-one,” and her transition from daughter to “free woman” sets the drama in motion. She can now legally make her own decisions. However, the patriarchy requires she settle down.

Irene has a clear sexual vitality and isn’t shy about being flirtatious with all three suitors at once. Still, she’s also calcifying into the porcelain housewife figure that will emerge after World War Two. Her overseeing Victorian father does everything to be sure she will become some man’s perfect angel in the house. We’re even treated to a whole living room performance, just so there can be no disputing her accomplishments and refinement, despite her flirtations.

Admittedly, they are not sturdy structures, but looking at their floor plans can teach us plenty about narrative design.

What baffles the film and its characters more than gender is the supernatural. Mysterious things happen “even in these days,” Mr. von Helldorf chides. The “these days” he’s referring to is his disenchanted age. In his lifetime, the world has gone from societies centered on religion to secular ones. Nonetheless, there are corners, secret rooms, that science and rationalism cannot enter.

This is where the film grows jumbled. The Blue Room starts as a supernatural salon with no rational explanation. In the end, however, it appears both uncanny and capable of being logically explicated. Yet this magical change is never fully explained.

If we venture down the hallway, we’ll come upon the Corridor of Mirrors (1948). Unlike The Blue Room, Corridor of Mirrors invests heavily in explaining things. Flashbacks reveal many events were not what they seemed. The film’s narrative derives its structure from this presentation. First, viewers witness an event that invites suspicion of supernatural causes. Then, later, a look back reveals what truly happened.

We open on Mifanwy Conway (film co-writer Edana Romney), shaken from her sleepy life as a wife and mother by a mysterious piece of blackmail. A lover, it seems, summons her. On the train to Madame Tussauds’ in London, she relates the story of how she met Paul Mangin (Eric Portman) and barely escaped his grasp.

Edana Romney has the kind of expressive, searching doe-eyes that are perfect for a story like this. As she tears open the doors of the titular mirrored corridor, we catch her eyes, wide in terror. In that moment, we see ourselves in her. As the film’s co-writer, Romney has developed a rich inner life for her character. Her expressions best illustrate that as Mifanwy has to wrestle with her desire, confusion, and terror.

Corridor of Mirrors begins as a classic noir, a woman haunted by her past, then moves into a Bluebeard-esque folktale with a man and his hallway of horrors. It adds a bit of the uncanny and wraps it all in a big melodramatic bow. Explanations that seek to make everything work within the film’s world also eat away at the tension. The film demands it all make sense yet doesn’t quite meet that threshold. There are some clear edges of the mirror that don’t quite fit the frame. Still, on the whole, Corridor of Mirrors is worth reflecting on for its bold attempt to bricolage so many film genres in one.

In a similar vein, Claude Chabrol’s 1963 film Bluebeard attempts to blend reality and folklore but is a bit more successful. Despite its English title, this is not a retelling of the Bluebeard tale. Its original French title, Landru, is more accurate. The film concerns the true story of Henri Désiré Landru, a serial killer active during World War One.

Thanks to a brilliantly wicked script by noted French author Françoise Sagan (Bonjour, Tristesse), Charles Denner plays the killer with a devilish aristocratic air that is both comical and critical. Moreover, Denner channels Landru’s belief that his class puts him above the law with aplomb. We may never root for Landru, but he undeniably draws us in. After all, we do agree to watch his dastardly crimes unfold for 115 minutes in part because Denner’s dialog, performance, and bald cap are so alluring.

Under Chabrol’s direction, each shot is elegantly composed within Jacques Saulnier’s lurid and impressionistic production design. The chamber that lends its credence to the Bluebeard conflation feels so singular and surreal that it’s at once campy and menacing. Juxtaposing this with Chabrol’s use of actual footage from WWI heightens the reality, bringing it somewhere between truth and fantasy. Though it may not be a Bluebeard tale, Bluebeard shows how quickly and seamlessly fact and folklore can fuse.

There is perhaps no harsher intrusion of reality than in Homebodies (1974). Like Charol, director Larry Yust uses real footage of housing demolitions to heighten the terror and stakes of his charming tale of eviction and revenge. Set against the gentrifying and razing of urban working-class neighborhoods in the 1970s, the film features a lovely cast of senior tenants who will kill to stay in their building.

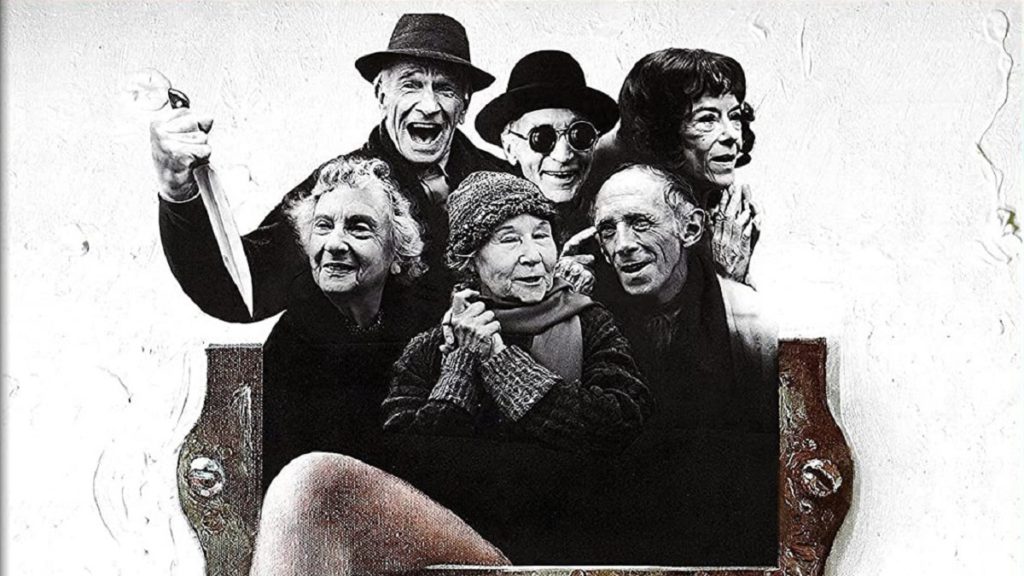

What starts as a dark ensemble comedy featuring Frances Fuller, Peter Brocco, Paula Trueman, and William Hansen ends as a bleak tragicomic commentary on elder dispossession and economic depression. Led by Mattie (Trueman), the gaggle of geezers slowly wreak havoc on the construction site and those attempting to evict them in a series of silly but menacing “accidents” that recall something out of Blake Edwards or A Fish Called Wanda. It’s a delight until we and the tenets realize it may not be enough to stop the vicious cycle.

Like the other films considered here, Homebodies has an element of the supernatural that is largely unexplained. And like the others, this incongruity reveals an attempt to say something larger than the world of the film. Each, in their way, wants to instill some mystery and magic into a secular life largely devoid of such things.

I think Homebodies employs the device best. The uncertainty introduced by the supernatural creates the possibility of an ongoing, cyclical time, as in the other three films. The other three films all involve trapped people, but Homebodies’s cynical apparition pushes the narrative into insightful critique. We know the cycles of dispossession continue. The film’s final specter lets us know that rebellion lives on.