KinoKultur is a thematic exploration of the queer, camp, weird, and radical releases Kino Lorber has to offer.

There are two documentaries available on KinoNow, filmed five decades apart, that bookend a period of queer masculinity marked by both visible changes and invisible wounds that remain all too familiar. The Queen (1968) and When the Beat Drops (2018), present queer masculine cultures — the drag pageant and bucking dance competitions, respectively, as related to and inspired by feminine spheres of culture, but decidedly separate from them.

Putting these two films side-by-side makes plain how much queer visibility has changed from the early days of liberation to the more recent days of America during the Trump administration, but there are chilling moments where we can also recognize that some harmful ideologies have yet to be rooted out.

Both The Queen and When the Beat Drops set out to capture moments of queer expression through pageantry and dance. In doing so, they celebrate these artforms for what they allow.

The Queen, Frank Simon’s now classic documentary, follows drag queen The Fabulous Sabrina as she prepares New York’s 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Contest. It’s grainy film, and its handheld camerawork has an archival quality that almost seems aware it’s filming for posterity. By having truly intimate access to these queens, Simon’s camera documents a glorious age of drag with monolithic wigs, Cleopatra cut creases, and feather boas.

But the drag is more or less secondary to the men underneath the drag. Watching this film now, post-Paris is Burning, post-Drag Race, we see how white and cisgendered this community is compared to what we know about the drag scene now. Given the precarious nature of sexual politics in the late 1960s, these are men (rightfully) worried about respectability and masculinity.

As the queens lounge about out of drag, their conversation turns to gender identity as the men share their struggles with being a man, a drag queen, and the roadblocks being effeminate puts up in their lives. Most have difficultly being respected as a man, despite wanting to be seen as such outside of drag. One queen shares a frustrated story of not being able to be drafted into the military to participate in colonialism because of how legibly feminine he is.

Unfortunately, despite being in an artform dedicated to celebrating and critiquing gender, many of them assert their masculinity through trans- and gynophobias, proudly sharing their preference for theirs and others penises, often at the expense of people with vaginas. Sadly, these reflect biases that we know also post-Paris is Burning, post-Drag Race haven’t left the drag community.

It should be noted that while the film streaming on KinoNow has this in it, the extended sequences on The Queen’s home video release fill in the history of these conversations quite well. The documentary short Queens at Heart included is not to be missed for people interested in snapshots of transhistory from the late 1960s.

While the gender discourse is treated as largely benign, it’s the racial discourse that ruptures through in the final act that The Queen is most famous for. Early on, racial conflict is foreshadowed by Sabrina making strict rules around “attitude” and “being uncooperative,” which too often results in increased policing of women of color. So when Miss Crystal finally fires back at the racist standards of beauty being used to judge the competition, it’s a high-stakes monologue worthy of a Pulitzer. She flips the script from being about temperament to being about race, linking the two and proudly proclaiming “I have the right to show my color, darling!”

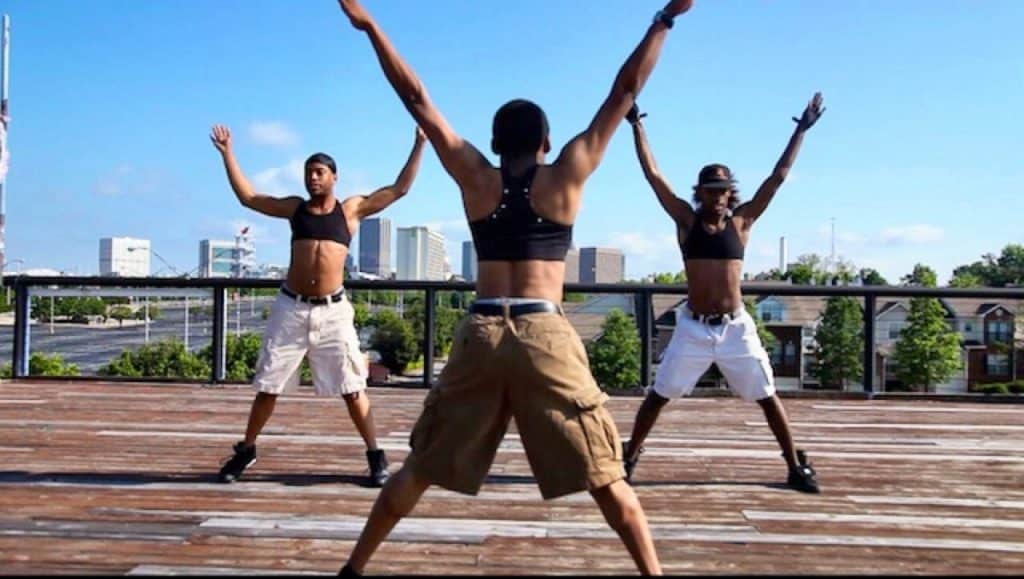

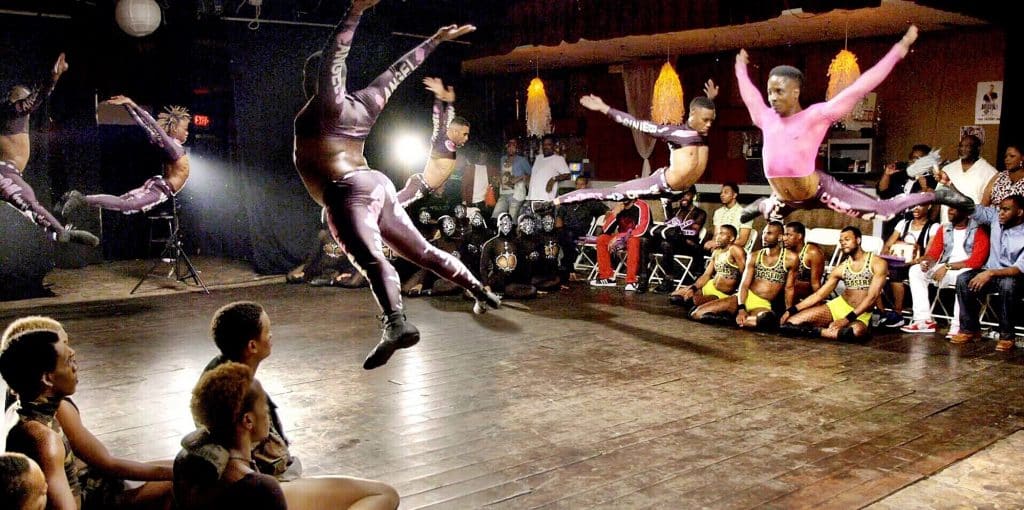

When the Beat Drops is all about people proudly showing their color(s). Director and celebrity choreographer Jamal Sims is unafraid to show the pain and struggle the Black men in his documentary have to go through as dancers in the bucking community. Part hip hop dance and HBCU cheer performance, bucking is an intense and expressive art form that requires focus and sacrifice.

Sims excels in showing the joy and ecstasy these men get from dancing. When it’s time for The Big Buck, the final dance competition, Sims breaks out his best visual direction, getting us right in on the floor and letting us see every bead of sweat, every grit of determination. His main objective is to show the drive and determination of these men, and in that he succeeds.

These men are not “just some kids on the street” as bucking legend and mentor Anthony Davis says at the opening of the documentary. They are men living the gig economy, often working two or three jobs, on top of rehearsals and competition. And this is made even more difficult by systematic urban underdevelopment robbing them of safe spaces to live, let alone dance. One of the most testimonial moments in the whole film is Sims and Davis walking in a parking lot that’s paved over an old club; Davis, seeing some floor tile left uncovered, takes some as a keepsake. All too often, fragments like these are all the men of When the Beat Drops are able to preserve of their community and their memories.

As we get to know Anthony and his Phi Phi crew, there is a palpable brotherhood that cannot be ignored. They help each other navigate the world as gay Black men, even when some are too afraid to say the words themselves. Some like Napoleon still have to worry about being too “out” for fear of losing their jobs. These are real struggles queer people face, but unfortunately Sims allows the blame and solution to be placed on femininity, rather than the structural gender and racial supremacies that perpetuate social outcasting.

Sadly the men go to great lengths to dissuade the audience from a common misconception, asserting that bucking is not for feminine, trans, or flamboyant “bottoms.” Despite bucking being inspired by and derived from women and femme dancers like the Prancing J-Settes from Jackson State University, When the Beat Drops’ subjects are not comfortable being perceived as feminine with the blame being put on femininity rather than society.

These apprehensions about explicit queerness and femininity quickly dovetail into conversations of respectability when a different bucking crew is on the news for wearing “skimpy” Santa outfits during a small-town parade. The men featured in Sims’ documentary more or less agree that the best thing to do is play into respectability politics to save face and not cause trouble.

Both The Queen and When the Beat Drops set out to capture moments of queer expression through pageantry and dance. In doing so, they celebrate these artforms for what they allow. Though their celebrations are tainted by racialized and gendered exclusions at their centers, the films make clear how the drag pageant and the buckingroom floor have the potential to foster radical queer joy and community.