The director talks the film’s rediscovery and release in the Criterion Collection.

In the wake of his first two feature films, the critically acclaimed cult favorites Repo Man and Sid & Nancy, British-born Alex Cox was officially the hot new filmmaker in Hollywood. His success gained him several high-profile opportunities. Instead, he chose to go to Nicaragua to make a film that would tackle the subject matter of America’s long history of meddling in the affair of Central American countries. Given the presence of the then-current Iran-Contra scandal in the news, the issue had become a hot topic. The subject of his film would be William Walker, a real-life Tennessee native who, under the aegis of Manifest Destiny, went down to Nicaragua. Once there, he took over the country’s presidency in 1856. He ruled for more than a year until his ouster. Undissuaded, he made multiple attempts to return to power until his eventual capture and execution by firing squad in Honduras in 1860.

While Walker was at one point arguably the most famous man in America, by the 1980s, that was no longer close to true. In fact, his name and actions were pretty much lost to history until Cox and his company, including screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer and star Ed Harris, took on the story. Instead of the staid, reflective biopic that many may have delivered, Walker was an offbeat film that combined dark humor, gory Sam Peckinpah-style violence, and genuine anger over America’s history of intervention in the affairs of other countries. Moreover, to emphasize how the U.S.’s current actions towards Central and South America had hardly evolved, the film deployed many deliberate anachronisms–the appearance of things like Coke cans, Apple computers, and copies of Time and Newsweek). The result was one of the genuinely distinctive and overtly political films released by a major studio during the 80s.

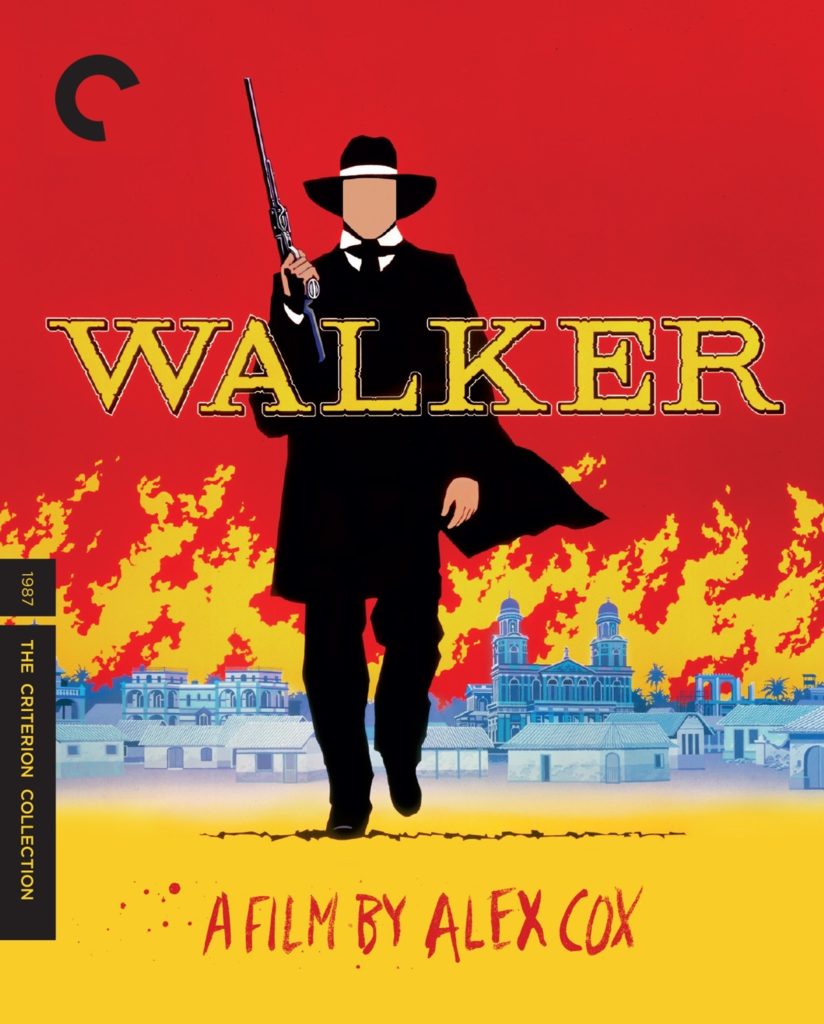

Well, sort of released. Universal Studios–whom Cox had quarreled with during the making of Repo Man–produced and distributed Walker. To say they were appalled by the results would be putting it mildly. After giving it a perfunctory release at the end of 1987, where it received mostly negative reviews that carped on the violence and the anachronistic devices, the studio pulled it. As a result, the film was almost impossible to see for a couple of decades. Then, a few years ago, Walker reemerged when Criterion put it out on DVD. The film finally began to find an audience that responded to the film’s unusual approach, Harris’s towering performance–which still may be the best of his entire career–and how it served as a still-potent commentary on American intervention. With Criterion reissuing the film on Blu-Ray, I had the opportunity to speak to Cox. We discussed this fascinating and powerful work, his struggles to get it made and seen, and even the time he was being tapped to direct a very different film about American misadventures south of the border.

When William Walker was at the height of his celebrity and influence in the 1850s, he was arguably one of the most famous men in America. Still, by the time you set out to make Walker, everyone outside of historians specializing in U.S. intervention in Central America had virtually forgotten him. Even today, if he is remembered at all, it is largely in conjunction with your film. When did you first come across his story?

Alex Cox: I went to Nicaragua in 1983 on a tour where you would go and visit the farms and meet the opposition political people to learn about the politics of the country from a leftist perspective. Because it was very close to election time, we couldn’t stay in Managua because there were no hotels available, so we had to stay in Granada instead, which is a much nicer town. Walking around the city, I came upon this old stone church which had this big plaque on the wall that said that this was one of the few buildings in Granada that was not destroyed when William Walker burned the city. I thought, “What—what was that all about? Who is William Walker?” I went back to the U.S. and borrowed the library card of a very nice historian from UCLA named Bradford Burns. I took out a bunch of books and began reading up on Walker.

When the idea for a movie about him came to you, was it because you found his specific story to be of interest? Or did you see it as a way to make a film that could use past events to comment on the present in the way that Robert Altman used the Korean War-set MASH to comment on Vietnam?

Cox: MASH is a good example, isn’t it? In the days of MASH, they couldn’t make a film about Vietnam because the studio would not have allowed it. I guess if we had tried to make a film about American foreign policy and Elliot Abrams and North and those other weird creeps like George Bush, we never would have gotten it done in a million years.

I suppose the historical aspect gave us more of a possibility of making a film in Nicaragua, which was our goal. If we made a film in Nicaragua and could involve some American movie stars, that would draw the press, and that would tend to create a different type of publicity from the largely hostile publicity that was existing in the mainstream media at that time about Nicaragua. Walker was the means by which to achieve that goal. Once we started making the film and especially during the editing, it became apparent that it was all about William Walker and all these other scenes that Rudy had included—different characters and events that were going on—we dropped them all completely.

Around this time, weren’t you also being solicited to make a somewhat different film involving the misadventures of American celebrities south of the border, The Three Amigos?

Cox: This happened several times. After we did Repo Man, Universal wanted the producers and I to do a film about American high school students who went down to Central America to save a friend who had been kidnapped by communists. This was Universal’s idea of a good film, and we passed on that. Then, about the time that I was about to do Straight to Hell, I was offered the opportunity to do The Three Amigos, which was this very expensive comedy with these guys from Saturday Night Live in it, which was about these three guys who go down to Latin America to sort things out. Strangely enough, it was kind of the same movie, only with a bigger budget, but I don’t think I would have been a very good fit for it because I was never very fond of the SNL crowd and the fact that they invaded and took over American cinema and displaced a lot of very good actors.

A key influence on the style of Walker is the work of the late Sam Peckinpah, primarily in regards to Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, which shares with Walker everything from key thematic concerns to the idea of having a contemporary rock star—Joe Strummer in place of Bob Dylan—supply the score and also appear in a small role. Another connection, of course, is that both films were written by Rudy Wurlitzer. Was the Peckinpah connection something that you had been looking at from the start or did it come up once Wurlitzer was hired to do the screenplay?

Cox: I had asked Rudy to write the script for Walker because of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. It seemed to me that Pat Garrett was about two guys seeking their own deaths who couldn’t get there but managed to pile up an enormous mound of bodies of other people, mostly innocent, along the way before achieving their apotheosis of being killed. That, of course, is the story of Walker as well—an individual who should have been put out of his misery a long time before who instead becomes this hero filibuster who takes an army of misfits to Nicaragua and causes multiple deaths and mayhem before being killed by a firing squad.

It seemed to me that the message of Walker is essentially the same as the message of Pat Garrett, so I really wanted Rudy to write it. Looking at Pat Garrett again and again over the years, it really struck me what a political film it is. I think it is the most political of westerns—it is the only one that addresses Lew Wallace and the involvement of the governor of New Mexico in the whole gunfight story. It is a great film that will shortly be re-released by Criterion, and I can’t wait to see which version they use since there are three versions of it.

One of the most controversial aspects of the film was the way that you utilized anachronisms—Coke cans, copies of Time and Newsweek, a helicopter—as a way to blur the line between past and present and to underscore that what was going on in Nicaragua at the time was still happening. Even though the device is not particularly overdone—I think the first example pops up maybe a half-hour in, it seemed t be one of the things that really upset critics at the time. How did the idea of including this device come about?

Cox: Right at the beginning. We both thought that it was very important that we didn’t want the film to be trapped in a historical bubble. A lot of times, if you make a film about a historical character, especially a bad historical character like Walker, it is usually seen through the eyes of a sympathetic journalist so that the events are interpreted for us, like The Year of Living Dangerously or Salvador. We didn’t want that; we didn’t want any sympathetic character in the film because we thought that all of the characters involved in this story were deeply corrupt and must be depicted that way.

Having done that, we were free from the sentimentality of characterization, and so it was easy to decide to not just leave this all back in 1853—let’s bring it up to 1988 and talk about what was happening right now and in the last 60 years where Nicaragua was dominated by the Somoza gang. When the Mercedes drives through, that shot gets a big laugh in Nicaragua because the Somoza family owned the Mercedes dealership. When Walker enters the church on horseback, that is not in any of the published histories of Walker that I have read, but everyone in Nicaragua knows that story, so you have to include that story because even though it is not part of the English language historical record, it is part of the historical memory.

The casting of the film is also quite interesting. At the time that you cast Ed Harris as Walker, he was best known for playing John Glenn, and in many ways, the two are alike in that both were famous individuals who attempted to become President, with Walker actually succeeding in that task. Marlee Matlin also appears in it as Walker’s late fiancee and I believe this was her first film role after winning the Oscar for Children of a Lesser God.

Cox: Marlee was like a gift from the gods. Ellen Martin, the woman that she played, was a deaf-mute and the most beautiful woman in Tennessee and Marlee was also deaf and the most beautiful woman that you could ever imagine anywhere and a wonderful actress and a really nice person. It was a fantastic opportunity to work with her. I wish she hadn’t been limited to playing roles that called for somebody who was deaf because she was so obviously a fine actor that she could have played lots of things.

We saw a number of actors who were interested in playing Walker, but they didn’t want to go down to Nicaragua or didn’t want to read—in those days, I was still living in the fantasy world where directors auditioned the actor. There were a couple of biggish actors who were interested in the part but who wouldn’t read, and Ed said, “I’ll read.” He was doing a movie up in Seattle, and we went up there. He read—he buttoned up his collar and got very straight and very repressed and did a fantastic reading. Now I can’t imagine anyone else playing the part.

The one aspect of the whole Walker saga that I have never been able to quite figure out is why, considering the subject manner and the approach that you were using, Universal decided to get involved with it. They had always been famous for being among the most conservative of the major Hollywood studios, and even when they would do something a little more radical, with films such as The Last Movie, Two-Lane Blacktop, which Rudy wrote, and your own Repo Man, they would almost inevitably find some way of sabotaging it in the end.

Cox: That would really be a question for the executive producer, Ed Pressman, because he was the one who set up the deal with Universal. It did seem really odd and a big mistake to have Universal fund the entire picture—it would have been much more sensible to sell them the American rights and sell the foreign rights to another company so that it would not have been so easy to suppress on a worldwide basis. In a way, what you said is an explanation. Back in the late 60s, Universal funded a slate of 6 or 8 independent New American Cinema movies for about a million dollars each, like The Last Movie and Two-Lane Blacktop and Diary of a Mad Housewife—really good and interesting American films. Then, when they were all done and delivered, Universal sabotaged them all.

They did the same thing with Repo Man. They never should have funded that film at all because they didn’t understand it and they hated it. At the same time, despite Universal’s hostility, Repo Man found an audience and became quite popular, and so I think there was that wish for them not to be caught with their trousers down a second time and to demonstrate that they were cool and would fund a good movie. They did fund a good movie, but then they screwed up the distribution.

Did they interfere at all with the film in terms of editing or changing elements of it or did they just write the whole thing off?

Cox: I think it was to just write it off. What I have tried to do in my filmmaking career has been tome short films around 85 minutes in length, with the exception of Sid & Nancy, which is just too long. If you make a film that is going to be short, it is very hard for the distributor to mess it up. If you make one that is 2 1/2-3 hours long, you know that your are going to be screwed, and it will be like with Sergio Leone and Once Upon a Time in the West—they will take it and cut it down to 80 minutes anyway. If you just make it 80 minutes, they can’t really mess with it.

The only other person who I can imagine making a film on the subject of William Walker at this time would be John Sayles but I am sure that would have resulted in a far more straightforward treatment. It still might have been a good movie since he is a great filmmaker but it almost certainly would have been far different from what you came up with.

Cox: Salvador is also a very good movie, but it is one seen from the point of view of an American journalist who is the “hero” of the film. We were lucky to not have to fit into those conventional narrative traps. Rudy and I were very conscious of that, and we didn’t want to make just a regular biopic. We wanted to do something more interesting and had more meaning—perhaps we were a little pretentious and grandiose in our thoughts.

When the film came out in the end of 1987, right at the time when the news was dominated by the Iran-Contra scandal, it was widely panned by critics and quickly pulled from distribution. However, it has held up quite well in the ensuing 35 years—even the anachronisms still feel relevant. Do you think that the film and the approach you employed might have had a better chance of catching on with critics and audiences if it had been made at a different point in time?

Cox: Not really. Things have actually gotten more conservative than in those days in terms of what the gatekeepers will allow regarding narrative. Things are more constrained and constipated than they were in the 80s. When we did Walker, that was the time when Derek Jarman did Caravaggio, which also introduced anachronistic elements, and a Russian film called Remembrance about Stalin which also broke the anachronism barrier. I think we were a lot freer as creative filmmakers in the 1980s than we are today. I think that was the ideal time for Walker to be made—I don’t think it could have been made later on because of how conservative things would become.

One reason why it still holds up is that when you look at it removed from the then-current news regarding Central America that was occurring during its production and release, it can be seen as a comment and indictment of U.S. interventions in general especially regarding Iraq and Afghanistan.

Cox: Unfortunately, it is an ongoing story that doesn’t change. We hoped back in the 80s when there was still a vestige of the anti-war movement left over from Vietnam that concentrated on Central America and defended Nicaragua, and shone a light on what was happening in El Salvador. Where has that anti-war movement gone? It is gone, but the times are now far more dangerous than they were in those days.