Double Fine’s bizarro debut remains singular 15 years later in how it explores characters’ minds—and the platformer genre’s own neuroses.

Amiable, punkish, and boasting his trusty soul patch, the 32-year-old Tim Schafer had just left LucasArts. It was January 2000. He’d been there for 11 years, having designed six games, written five, and programmed three. Two of them—biker adventure Full Throttle and Aztec noir Grim Fandango—were his own brainchild, but it was at the turn of the millennium that the company starting strafing away from adventure games. Thus, Schafer left to found his own studio. The name? Double Fine Productions. His philosophy? That “games could be art.”

One word in that sentence makes a specific difference—could. That word also feels like a crux to the company’s first project, Psychonauts. When it finally debuted in April 2005, it presented itself as an interactive psychosocial exhibit and said, “Games are art.” A platformer/adventure game it may be, but it’s also one that toys with, deconstructs, and reshapes gaming structures to reflect its own psychology as well as the psychology of the genre itself.

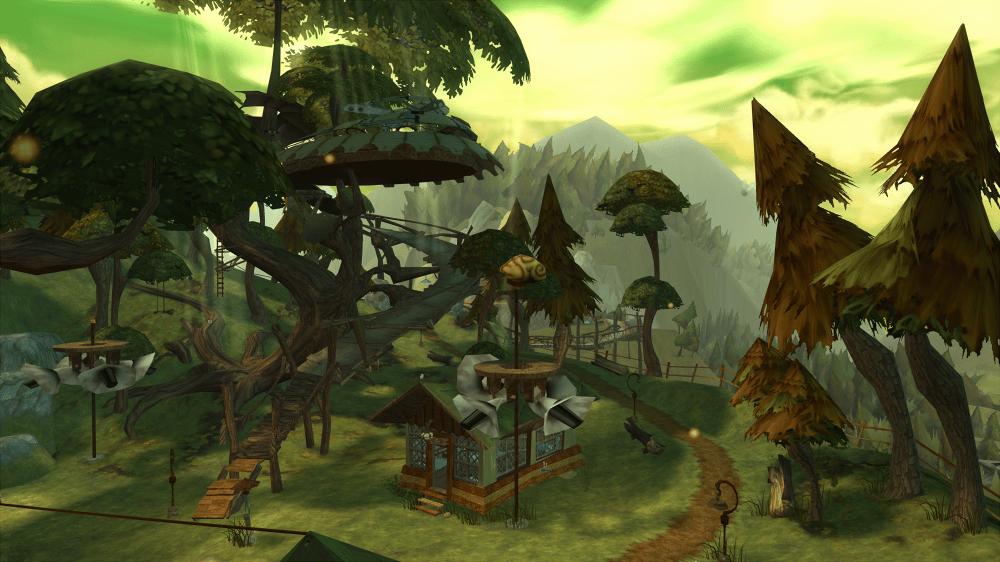

In it, the audience takes control of Razputin “Raz” Aquato (Richard Steven Horvitz), a burgeoning psychic who’s fled the circus. He’s motivated, a bit nerdy, and would come off more precocious if it weren’t for his surprisingly acidic tongue. Most of all, he’s itching to practice his powers away from his authoritarian dad. Thus leads Raz to Whispering Rock, a government summer camp where counselors (read: secret agents) teach kids “to soar across the astral plane.” It doesn’t take long for things to go awry, though, when death plots start hatching and tots start to turn up brainless.

But the central conceit comes from an idea Schafer had to scrap from Full Throttle: going into the human mind. The levels in Psychonauts are representations of people’s psyches, blending cartoon, caricature, and Carl Jung to flesh out its universe. Observational and nonlinear interactions take place in the real world. Dialogue tree conversations occur in mental worlds. Video game logic and dream logic bring more out of each other as the campaign progresses. The mythology connects it all. Then the main question arises: Just how much does this game feel like actually playing a game?

Many of the medium’s best offerings “don’t feel like playing a game” due to sheer immersion, and while that’s an achievement in and of itself, Psychonauts builds upon that like a mixed-media gallery. Its personality, for example, isn’t just due to its dialogue and cutscenes (of which there are hours). It’s also because of its inspirations.

Its filmic influences range from Godzilla to Capricorn One. The visual style blends German expressionism and stop-motion animation, and while some moments are akin to Rankin/Bass, lots are closer to Victor Sjöström or Robert Wiene on acid. Once the penultimate level reveals itself to be a day-glo homage to black velvet work, it all feels like a bona fide art show that just happens to be a game. It all adds up to a varied and deep play through. Where Psychonauts goes beyond, though, is how it juggles inspirations of different mediums by conflating dream logic with game logic.

Take the allusions to the Jungian approach, for example. Some of it is more obvious. (The closest thing the game has to a level select screen is a realm called the Collective Unconscious.) Some of it, like how much backstory Schafer and Erik Wolpaw give each character and to what extent they resolve it, is borderline seamless. Then there are more elements, like how the game uses archetypes and extends them to the overall structure. Its aesthetics are striking throughout, but lots of its best qualities don’t solely come from the gameplay.

Rather, they come from how the game introduces, draws out, detaches, and reshapes platformer/adventure tropes. On a textual level, it signals the game’s own psychology. In a larger context, it reflects on the psychology of adventure games themselves. Most games are defined by turning the audience into a player. Psychonauts, on the other hand, invites the audience to become a watcher just as often. Characters forge relationships only known to the audience if they take the time to not play, to sit and listen for minutes on end.

The first half is full of dialogue, archetypes that make up a social caricature, and tutorials woven into its mythos. Some aspects hint at truly bleak material mined expertly for laughs, like two screechingly jovial kids (Andy Morris and Colleen O’Shaughnessey) whom the game reveals as suicidal. Some children deal with sitcom-type love triangles; one boy (Brett Walter) grows from a human punching bag to a mob boss in training.

Truthfully, it has the scope and progression more akin to a television series. In between these segments come levels to slowly reveal the plot, and adjacent to those are collection quests tethered to the camp setting. All of these are linked by the aforementioned sitcom-style characterizations and in-game cutscenes. But while this push-pull between action and inaction every few minutes is inherently risky, Psychonauts prides itself on its crooked pacing, accruing its own prose across two distinct halves.

It’s by the second half of the game that day turns to night. The location shifts from the camp to its literal and figurative shadow in the form of an abandoned insane asylum across the lake. The darker content becomes more pronounced. It’s also at this point when gameplay takes center stage and, most importantly, when Psychonauts adopts a lonelier disposition. This dissonance between observation and activity points to Carl Jung’s writing in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious:

There are as many archetypes as there are typical situations in life. Endless repetition has engraved these experiences into our psychic constitution, not only in the forms of images filled with content, but at first only as forms without content, representing merely the possibility of a certain type of perception and action.

While the technical and interactive merits never waver, the feeling of playing a video game becomes more pronounced. Raz gets new psychic abilities within mental worlds as opposed to “earning” them like in the first half. The collectables, such as in-game currency and markers to rank up, shift dramatically from filling the real world to filling mental levels. Signifiers of completion become much more black-and-white; locales get more surreal in space, time, and identity. All of the mechanics introduced early on become just another part of the larger dream.

And yet it makes sense. Dreams, as Jung wrote, are “a way of compensation for the dreamer’s current, conscious attitude, which are in some way one-sided or incomplete.” Gaming does something similar. This is especially true of the adventure genre, what with its plethora of moves and wayward collectables that tie together with a bow by the end. Further complementing this from conscious to unconscious is the progression of interactions. Human interactions start off as real, soon becoming little more than metaphorical representations of characters’ psyches.

One level a little more than halfway through, for example, focuses on Gloria von Gouton (Roberta Callahan). In one of its more pervasive filmic allusions, she’s a Norma Desmond type plagued with borderline personality disorder. Her fear of abandonment is exacerbated by her mother’s suicide; her celebrity feeds into an inner-critic figure. After exploring her mood swings (represented by “happy” and “sad” sets that change on a dime), the audience confronts the roots of her issues and their lasting effects.

The audience spends as much time watching amateur meta-theater as they do using the setting, adapting Our Town-influenced production design in the context of a 3D puzzle. The audience is soon tasked with resolving her (and others’) traumas in order to meet the game’s narrative conclusion. The progression becomes more black-and-white, the concept of Raz’s (and the audience’s) purpose more Jungian.

Like how Jung considered the psychotherapist a sort of shaman, Psychonauts casts the audience in a fictionalized version of this role. They’re asked to collect and solve in a paranormal context. They help others find their sense of self in the process. That isn’t to say the results are all the same, though: In one of the game’s most known levels, Raz travels into the mind of Boyd (Alan Blumenfeld), an asylum guard exhibiting paranoid-schizoid personality traits brought on through ambiguously external forces. His psyche is a salad of suburban streets and s’more-filled schemes, the game utilizing his background to satirize American life as the audience uncovers a conspiracy.

While Psychonauts allows Gloria to confront the root of her issues, the game’s construction only allows the audience to assuage Boyd’s symptoms, lessening his condition from active to residual. There’s a nuance beneath the nuttiness, and it all ties into itself. The writing lends great life to the experience, and that pathos already gives the game something to say.

However, this is a game that also has a viewpoint to transcend the goal-oriented roots of its genre. The world of Psychonauts is more than just interactive. It knows its archetypes, taking the time to cast the parent, the child, and the hero against birth, death, and power. “For the sake of mental stability and even physiological health, the unconscious and the conscious must be integrally connected and thus move on parallel lines,” Jung wrote. “If they are split apart or ‘dissociated,’ psychological disturbance follows.”

Here, parallelism isn’t just a matter of characters finding their sense of self. It’s inherent to the art’s construction altogether. Psychonauts recognizes its characters through the images that come from within them. In this context, however, they just so happen to be collectables in a video game. That’s its medium of expression, and it wouldn’t be the same otherwise.

By the last level, Psychonauts detaches Raz’s brain from his body, trapping the audience in game/dream logic until the end. The mechanics explode to the point where the very act of playing instead of observing becomes a trip unto itself. There’s ruthless platforming. There’s a final redemption of all those wacky collectables. And of course, there’s an escort mission to make audiences pull their hair out. It’s also when it cooks up empathy for its cartoonish, potato-shaped antagonist in a fever dream that melts all of its inspirations together like the machine from The Fly.

It’s no real surprise that the game didn’t do well upon its initial release despite its critical acclaim. It came out at the end of the sixth console generation’s lifespan and was a far cry from Resident Evil 4, Call of Duty 2, and the influx of commercially licensed games in the mid 2000s. It’s as weird to behold as its humor is off-color, and it’s punishingly difficult at points too.

However, it’s also teeming with life and ingenuity, a clear example of something made for artistic value instead of financial gain. It’s a movie to rewatch, a series to sift through, a museum to explore, and a game to lose oneself in.

Psychonauts is, by all accounts, a work of art.