Alan J. Pakula’s first installment of his Paranoia Trilogy remains a slyly feminist tale anchored by breakout work from Jane Fonda.

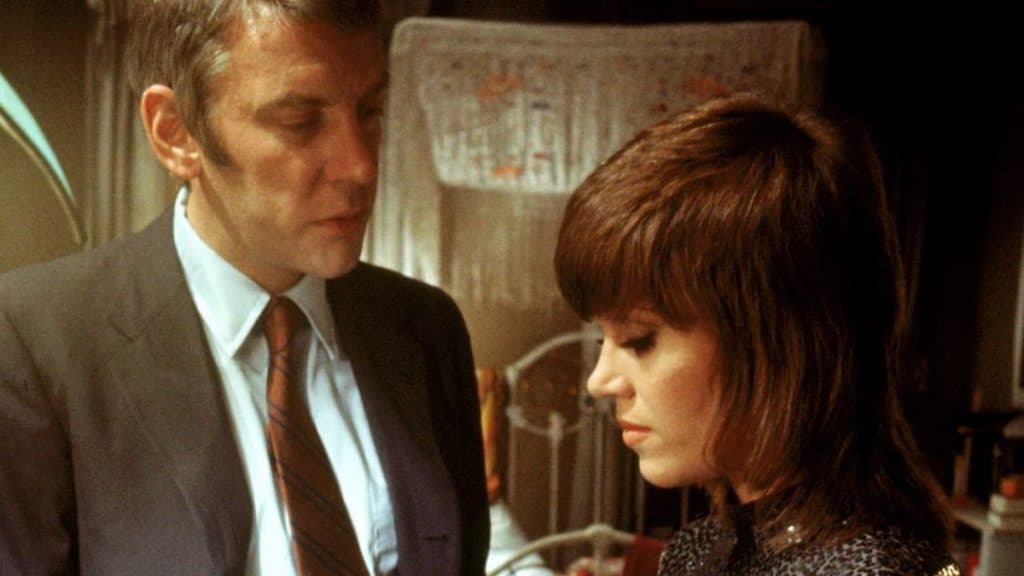

Alan J. Pakula’s Klute is full of surprises, not least of which is its title. It takes its name from one of its principal characters, small-town detective John Klute, who is tasked with investigating the disappearance of a family friend. Played by an achingly young Donald Sutherland, Klute must head to the festering metropolis that was 1970s New York during one of the city’s most infamous low points and enlist the help of Bree Daniels (Jane Fonda). She’s a high-class call girl who may be connected to the disappearance—and much more.

It’s the perfect setup for a sexploitation film, but 50 years after its release, Klute is still a rarity: a movie about a sex worker from the sex worker’s perspective. Released in 1971, a mere three years after what might be Fonda’s most iconic role as the title character in the 1968 sci-fi cheese Barbarella, the ‘60s are definitely over. The star sheds her breathy, Monroe-esque voice and blonde tresses for a feathery, brunette shag as the film delves into Bree’s complicated psyche to explore modern alienation, and what we now refer to as toxic masculinity.

Its views on Bree’s profession are also ahead of its time. More akin to the underrated Hulu series Harlots or the 2019 film Jezebel in its firmly feminist (or more accurately in the case of the latter, womanist) view of prostitution. It’s decidedly unsentimental, presenting it as neither morally repugnant nor empowering, but merely an avenue that women can potentially find empowerment from in a patriarchal world.

That it succeeds is mostly due to Fonda. Calling her performance powerhouse would be a grand understatement. If anyone had any lingering doubts about her ability to transition from ingénue to more adult roles after her turn as a cynical dancer in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, Klute put them to rest.

Andy Lewis & David Lewis’ screenplay focuses so much on Bree’s life and complexity that it’s feasible to consider its title as a kind of Trojan horse, similar to how Orange Is the New Black showrunner Jenji Kohan used Piper, the classic (white, blonde, middle class) girl next door as an entryway to exploring the lives of marginalized women of color. It’s certainly difficult to see Klute being made or even marketed without the reassurance that there was also an easily recognizable type, that of the strait-laced, all-American cop who was sincerely interested in nabbing the bad guy and protecting his damsel.

In theory, Klute may have something of a hero complex in regard to Bree. She’s indeed in danger from an unknown stalker who may be responsible for other deaths, but Klute mostly falls into the non-toxic category as he and Bree eventually form a genuine connection. Klute is more interested in saving than condemning her, even after he sees Bree at her most cruel and messy. That Klute not only sees her in moments like these but also continues to is what’s truly unsettling to her, who’s far more comfortable being stalked from a distance than being vulnerable and truthful with another human being.

In Bree’s world, connection may be the most dangerous thing of all. Opening up to another person means giving up the control she so desperately craves, which she’s so often denied. An aspiring model and actress, she endures the indignity of various casting calls where she and other women are routinely sized up and dismissed. (I feel the same outrage on her behalf as I do for Liza Minnelli in Cabaret. How dare they display such an appalling refusal to be enchanted by the goddess in their midst?)

That Klute not only sees her in moments like these but also continues to is what’s truly unsettling to her, who’s far more comfortable being stalked from a distance than being vulnerable and truthful with another human being.

We never see Bree more assured than when she’s with various johns, and she’s clear-sighted enough to know it’s not exactly her they want. What counts for her is that she’s wanted. Her payment is reassurance that she’s played her role to perfection, even if she finds no physical enjoyment from the act itself. When she begins to enjoy not only sex with Klute but also his company, she longs for “the comfort of being numb again.” She longs for when she at least felt like she had agency.

But power is a funny thing, and Klute is far more concerned with its dynamics than any mystery surrounding its killer, revealing their identity 40 minutes in. As Bree and Klute make their way through New York’s seedy underworld, Bree is forced to consider just how little power she really has—how many of her friends have surrendered theirs, some permanently. Any one of them could have been her, as she’s finally forced to admit. But Bree is no victim. The film itself refuses to make her one, just as it refuses to show us the grisly consequences that can await the slightest misstep.

That refusal may just be the most remarkable thing about Klute, which is uninterested in instituting a new version of the Production Code by making such an intelligent, developed woman a mere martyr. Bree’s choices are far more varied than marriage or death. Just where she’s going is left open-ended to a frustrating degree, but perhaps the biggest twist of all is that this all began not with a husband living a sleazy double life with the city interloper. It was a decent man in a happy marriage who discovered the real predator was living in their midst all along.