Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. For July, we honor the chameleonic genre-bending of the recently-passed Joel Schumacher, who embraced camp thrills and pulp trash in equal measure. Read the rest of our coverage here.

The Number 23 is an overthought movie about overthinking. For a film about the inescapable order, the script is mostly chaos. It feels messy, as if it’s deliberately trying to occlude the fact that the script has no there there. By the time the credits roll, the x at the center still remains unsolved. The film works in a theoretical sense, but it doesn’t add up to anything concrete.

Now, like Jim Carrey’s madman at the center of Joel Schumacher’s 2007 thriller learns, solving the equation is a fool’s errand. Instead, it’s perhaps best to try tomake sense of the equation The Number 23 is trying to put together, and figure out why x remains unsolved. For all its flaws, it still fits neatly within Schumacher’s list of thematic concerns, combining artistic themes found in his previous thrillers Falling Down and Flatliners to create a uniquely meta-film that helps us sense the hidden order structuring socio-reality.

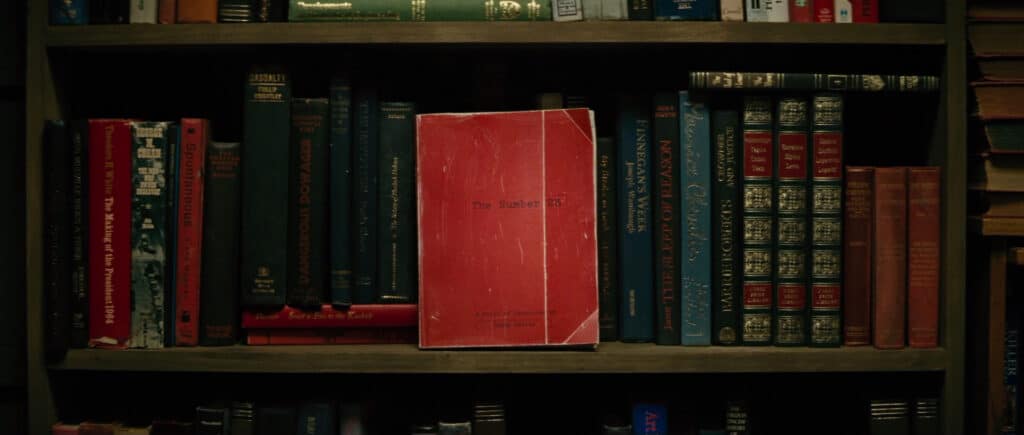

The Number 23 reteams Carrey and Schumaker, except this time the creeping menace threatening Carrey isn’t Tommy Lee Jones—it’s quantum mathematics. We open on Walter Sparrow (Carrey), a meek and mild animal control worker whose life seems directionless until he and his wife, Agatha (Virginia Madsen), come across a bewitching book. It’s The Number 23 by someone named Topsy Kretts. (You’re allowed to groan.)

Walter becomes consumed by the book and its cryptic tale of murder, a troubled Nick Cave-like detective named Fingerling, and a mysterious number ordering the world. He begins to see himself in the book, to see the number 23 everywhere. It consumes him. And it soon becomes clear Walter, Fingerling, and the number 23 are horrifyingly intertwined in ways that seem to defy logic.

This, perhaps more than Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, is Carrey actively playing against type. Though he finds tender moments of humor, The Number 23 is largely an exercise at how furrowed his brow can be. Playing Walter and Fingerling, Carrey moves from pleasant to paranoid to possessed with skill. Madsen, ever a thriller maven, is exacting in every choice she makes. Though the film has flaws, they’re not in Carrey or Madsen’s performances.

Also on full display are the talents of cinematographer Matthew Libatique. Libatique, having the year previously been the cinematographer for Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain and Spike Lee’s Inside Man, merges these two disparate styles to make a look that can only be described as preternatural. As Walter gets more and more obsessed, the film becomes more stylized, his obsession bringing a perverse enchantment to his mundane life. Likewise, when Schumacher takes us into Fingerling’s story, Libatique serves full digital film fantasy with lots of over-saturated blues and greys that in 2007 probably read as passé but now feels more like a conscious “look.”

These obviously cinematic qualities are important for understanding the possibilities of The Number 23. The film itself is about hidden orders revealing themselves, and these moments of capital-C Cinema are the instances when the filmmaking shows itself to the audience. Despite the chaos of the world and confusion of the script, there’s a clear visual order being set and controlled for us.

What The Number 23 does well is sensationalize hidden systems, using conventions of the thriller to make us feel the terror of an inescapable, objective reality in which our agency is an illusion. The pressures to decode the hidden order, remove yourself from its oppression, or overcome it, weighs heavily on one’s psychology. “Fun” and “choice” lose their meaning and we become alienated from ourselves, causing mental health to decline.

Walter embodies this totally. As he uncovers that the world is not his own, where meaning comes from equations set and defined by metaphysical outside forces, he loses all happiness. The inscrutable math becomes literally written on his body, and he experiences the madness of conscripted choice, driven insane trying to understand and beat the system, further isolating him from his family and community. He is powerless in a systemic predestination, shattering his identity.

We’ve seen Schumaker explore similar concepts before. As Clint Worthington points out in his thought-provoking response to D-FENS, Michael Douglas’ character in Falling Down, “economic anxiety” is “the root of [D-FENS’] rage.” The violence he unleashes is a “flailing reflex of a dying breed: the mediocre white man the American Dream was always seemingly designed for.” The important word is “seeming.” D-FENS’ break comes in realizing the American Dream wasn’t actually built for him; that he too is but a small cog in a vast and ever expanding machine.

[…I]n focusing too narrowly on its rote pet project of numerology, the formula here feels more than a little unsolvable.

Finding that the hidden order sold to them is also rigged against them, even actively betraying them, brings the system oppressively into focus for these two characters. Walter also sees the gap between the map and the territory and explodes both outwardly and inwardly. Instead of simply giving his life meaning, exposing the systemic reality overloads his world with meaning.

The film has plenty of affective potential to say something about life under oppressive invisible orders. Uncovering a hidden order, after all, feels like a treasure hunt to find capital-R Reality. That’s what keeps the heart of all conspiracy beliefs beating. One of the more clever things Schumacher does is not allude to the pre-existing conspiracy around The 23 Enigma, so that if audiences left the theaters and felt compelled to research for themselves, they would find an already laid web.

It’s a noble effort to show the pain of waking up to the horror of constructed reality, and The Number 23 remains a unique attempt. Despite the variety of Schumacher’s filmography to date, his interest peeling back the layers of society to reveal its hidden oppressions shines through in the vamps of The Lost Boys, D-FENS in Falling Down, the Batmanses (to a certain extent), and The Number 23. But in focusing too narrowly on its rote pet project of numerology, the formula here feels more than a little unsolvable.