Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. For July, we honor the chameleonic genre-bending of the recently-passed Joel Schumacher, who embraced camp thrills and pulp trash in equal measure. Read the rest of our coverage here.

At the start of Joel Schumacher‘s Phone Booth, we can peg Stu (Colin Farrell) as a hustler with ambition in his heart. A low-level publicist playing at being king of Manhattan, he struts around down 42nd Street like the lion of the urban jungle. However, when he steps into a phone booth to call his “client” Pam (Katie Holmes, in a thankless part), we can see right away what an empty suit he is.

Most of his nonsense seems more about his sense of self anyway. He takes off his wedding ring before he calls, a ritual to rationalize his betrayal of his wife, Kelly (Radha Mitchell, also a thankless part). He wears clothes and jewelry that look decent enough to pass as the real thing from a distance. Even Farrell’s wobbly Bronx intones help. Stu is so false he can’t even maintain the accent of his native borough.

And he’s noxious and clichéd in his slick emptiness. He wants to cheat with the first younger woman who gives him the time of day. He lies to his assistant (Keith Nobbs), a restaurateur (Josh Pais), and all of his “favorite” clients like Pam or ridiculous rapper Big Q (Ben Foster, delighted in taking a small role over the top). Basically, if he talks to you, he’s lying to you—or he’s treating you like garbage because you can’t help him.

Does that mean he deserves his fate though, several hours trapped in a phone booth with the constant threat of death hanging over his head as punishment? You can almost see the whiny intellectual types who signed that Harper’s letter pointing to the screen: “See? See? This is exactly what the modern discourse is like! A sniper rifle trained on him for what? Hitting on an attractive woman, massaging the truth, breaking his wedding vows? We’re all under attack like this!” But honestly, Phone Booth is too interesting and tightly coiled a thriller to be reduced to that kind of facile analysis.

Opening on the entering a piece of technology shot that was intensely popular at the moment—but would not reach its existential crisis inducing apex until Michael Mann’s Blackhat—Schumacher and Cinematographer Matthew Libatique sell the viewer of false bill of goods. From the inside of a phone, we push through the clouds to the island of Manhattan to a group of busker break-dancers in Times Square. All the while, a voice of God voiceover intones statistics about phones that seem so out of date as to be something from the ‘50s, but not less than 20 years ago.

On first blush, it seems like an attempt to introduce scope into a movie with almost none. It’s similar to how plays adapted into films will often feature multiple locations to remind you “this is a movie!” even as the dialogue remains aggressively stage-bound. However, years removed from the film’s release, and knowing aspects of Schumacher’s life story, the text becomes richer.

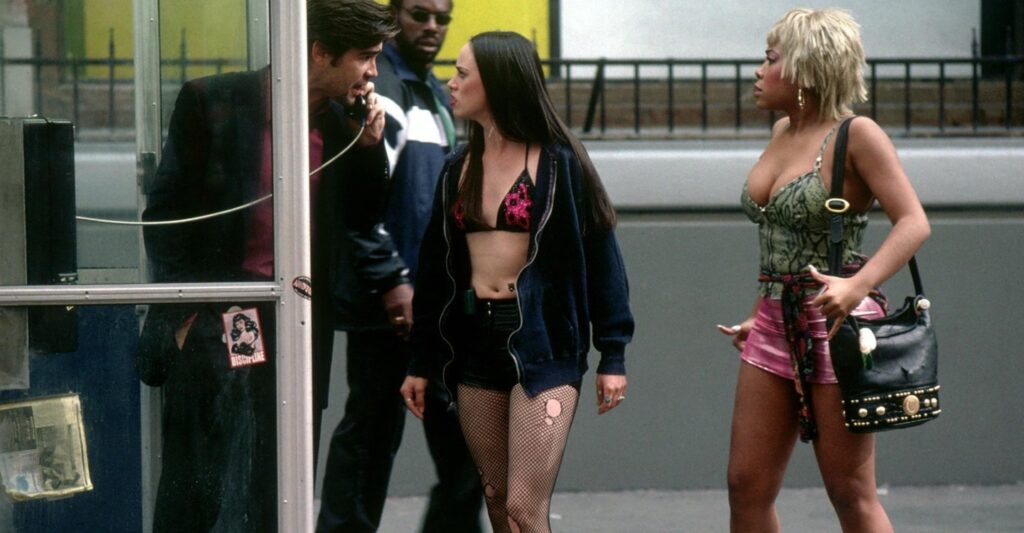

The director was mourning the end of his New York. Rudy Giuliani was already years into his project to expel either sin or life—depending on whom you ask—from Times Square. In 2002, the elements of the area’s past and future were awkwardly in tension. Times Square at that point was both a place where you could visit the M&M store and note an adult entertainment club by the name of Sugar Walls less than a block away. The buskers and prostitutes still worked the streets openly, but the writing was on the wall. It wouldn’t be long before the costumed characters hustling for money for pictures would be the new entrepreneurs.

Schumacher, who by many reports, strode the streets of Manhattan in the ‘70s like an amorous colossus, clearly had mixed feelings about the whole thing. He, like the phone booth Stu would find himself stuck as his world came apart around his ears, was a dinosaur. The problem is that Schumacher was not a rather dim prehistoric creature or an inanimate bit of technology. He could feel his obsolescence bearing down on him.

In this way, Phone Booth becomes a strange sort of cousin to Schumacher’s earlier death-pondering offerings like Dying Young, Flatliners, and The Lost Boys. The difference is that Schumacher is not considering physical death but rather a kind of living demise. How do you live when you’ve watched your world be taken apart by the AIDS crisis, terrorism, technology, and politics for two decades?

Phone Booth holds nearly all of these historical forces up to the lens while staying so coiled that you can easily ignore them. The Caller (Kiefer Sutherland, doing a hell of a job as a disembodied voice) is right-wing moralism, the kind that would put a slick publicist like Stu, an insider trader, and a pornographic film director on the same level of wickedness. In Schumacher’s—and likely writer Larry Cohen’s—eyes, the Moral Majority had spent years raging against moral relativism while creating its sort of cracked mirror opposite. It’s a perspective where all sin is equally terrifying, where just thinking about cheating is just as bad as the exploitation of women.

In Schumacher’s—and likely writer Larry Cohen’s—eyes, the Moral Majority had spent years raging against moral relativism while creating its sort of cracked mirror opposite.

The police, led by Captain Ramey (Forest Whitaker), are highly militarized tools of the state. One moment they’re taking tickets from Stu for gossip on celebrity drug problems, the next they’re in SWAT gear with multiple guns trained on a single man who hardly seems an active threat. The film pulls in the case of Amadou Diallo, shot at 41 times by Bronx cops while unarmed in his own doorway. (This was back in 1999 for those who might try to convince themselves that the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd are a recent phenomenon.)

Whitaker’s performance is interesting in this framework, as he seems the “good” cop everyone would cite in reply to an ACAB comment. He’s kind, smart, and seems emotionally vulnerable, wounded by years of work at a thankless job. Yet, he’s also a man who got so derailed by his marriage falling apart that he was ordered by the NYPD to seek professional help. He’s a cop who had some part in a recent bad shooting. He’s our hero cop today, but on another day, that clearly might not be the case.

Schumacher even accidentally anticipates bigger changes. The kind of work Stu does as a publicist, complete with calling print newspapers to ask if they got his faxes and bragging about network TV coverage, has dried up and turned to dust since Phone Booth’s release too. The entire movie is now a kind of monument to a place that no longer exists and several dead ways of life. Only the crushing capitalism of Times Square and heavily armed NYPD endure.