Kate Winslet and Harvey Keitel deliver powerhouse performances in Jane Campion’s cult-deprogramming dramedy, but the script fails in its thoughtless colonialism.

During her appearance on Inside the Actors Studio, actress Kate Winslet reenacted a day on the set of Jane Campion’s Holy Smoke! in which Harvey Keitel was a dog. As part of an improvisational exercise to “deepen the intimacy” between the actors, Winslet’s objective was to help the dog to die. Despite her very English hesitations, after many minutes of whimpering and yowling soundtracked by Enya, the canine Keitel finally “dies.” Winslet gracefully excused herself, found a secluded place, and burst into laughter.

The students in the audience laugh knowingly at this story. Such improvisational etudes are common in classes on Method Acting, of which Keitel was a famous (albeit brief) student under one of The Method’s most famous instructors, Stella Adler. These bounded exercises help free actors to explore new facets of their relationship and constitute a consciousness for their characters. They are, at times, ridiculous.

The students don’t get the usual caveat of “but I learned so much and am better for it.” Winslet never moves past her cynicism towards The Method. Instead, she apologizes to a non-present Harvey for telling what she considers an embarrassing story. She still maintains she didn’t learn a whole lot from the experience.

Such an exercise is foreign and largely unnecessary for Winslet, who is part of an English tradition of acting that is more text-driven than The Method’s experience-forward style. By the time Holy Smoke! was made in 1999, Winslet had already performed a stunning array of characters from independent dramas like Heavenly Creatures (1994) and a definitive turn as Ophelia in Hamlet (1996) to the blockbuster action-romance of Titanic (1997).

Despite this, Winslet’s reaction is entirely appropriate for her role as Ruth in the Holy Smoke!. Ruth resists the methods of Keitel’s PJ Waters, the man sent to deprogram her. By challenging him with her self-assurance and gender, Ruth exposes the flaws in PJ’s ideology and techniques, which sends him reeling.

Holy Smoke! is a film about transforming consciousness and performance, about changing the way one acts. When they’re alone, PJ and Ruth become not unlike scene partners: learning to develop intimacy, trust, vulnerability, and create a new world. PJ has a method just as Keitel the actor has a method. Both have the same objective: to strip away ego or psyche and rebuild anew. Though such methods can be critiqued and overturned by gender, other social categories remain unexcavated.

Unlike past Campion protagonists Ada McGrath and Isabel Archer, Ruth is an explosive, rebellious, and vocal character from the very start.

Holy Smoke! opens with Ruth traveling on a bus through India. Post-1960s enlightened orientalism abounds as Neil Diamond’s “Holly Holy” plays over the credits. Like the Flower Generation before her, Ruth has come to fix herself. Yet already, she’s far from peace. Before she’s even off the bus, an Indian passenger molests her.

But Ruth is immediately whipped up by the classic exoticisms of India — its smells, its density, its spiritual permeability. All it takes is seeing a group of white women walking slightly slower than the Manson sisters and Ruth whisks herself away and into the religious community, leaving her friend Prue and home life behind. It’s a nondescript Hari Krishna-like religious group but once inside, her third eye is opened, and she’s changed forever.

Back home in Sydney, Ruth’s folks are starting to panic. Prue has returned from India and told Ruth’s parents about their daughter’s religious transformation. Horrified, her parents hire PJ Waters, an American cult “exiter” or deprogrammer to not only bring back Ruth’s body but bring back her mind as well.

PJ’s services come at the extra cost of following his unusual methods. For him, “exiting” is “a precision exercise,” a partnered exercise, an “intuitive conversation.” Deprogramming requires a unique setting to “steer the subject toward a breakthrough [or] breakdown.”

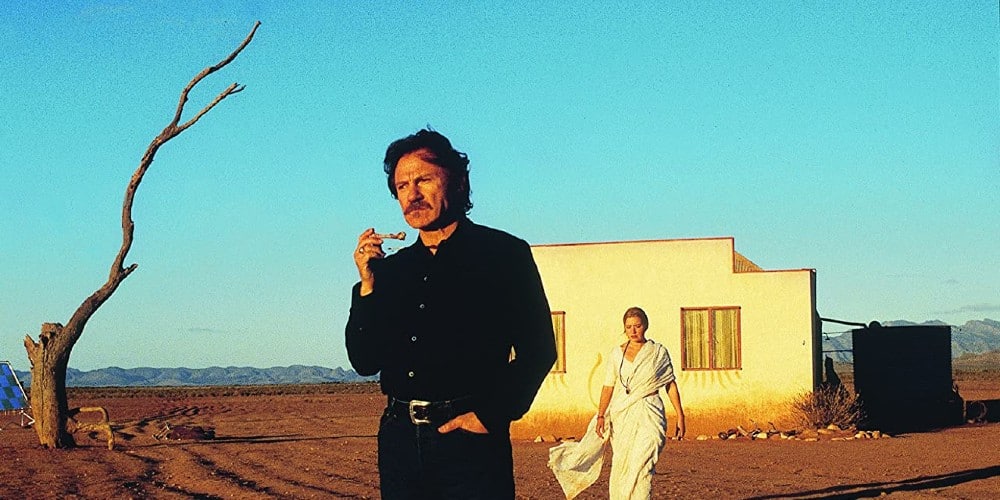

Step One: Isolate. PJ needs to get Ruth’s attention and respect. After a harrowing experience being encircled and trapped by the men in her family, pleading with her brothers Robbie (Dan Wyllie) and Tom (Paul Goddard) for one final reconsideration, Ruth bends to PJ and agrees to go with him further into the outback. Once settled into their “safe space” shack, the tension begins to simmer. “The heat goes on.”

Day Two: “Remove all her props.” PJ wants to upset Ruth by clearing all remaining links to India and provoking her with cynical questions about her faith and experiences. Yet Ruth remains firm and properly evasive. She isn’t brainwashed. She’s on a spiritual journey. Her resistance and steadfastness cause PJ to be the first to roll to a boil. He erupts at Ruth, calling her a “man-hater” for being “ungenerous” and not “giving” more of herself as per their contract. He’ll show her.

As part of the “deprogramming” stage, the second evening also hosts a screening of a brutal and unflinching documentary about famous cults, their victims, and their aftermath. While it initially appears that PJ’s methods are getting through to Ruth by the end of the night, when the pair return to their sequestered homestead, Ruth acts out, burning the saris PJ has taken from her. The “love” she felt from her guru Baba has faded. She has one final visceral release before wholly offering herself up to PJ.

…methods like Stanislawski’s acting technique and PJ’s psychological deprogramming assumed an essential masculinity to their “pure” subject.

The pair wake up on what is supposed to be their third and final day together, though it’s unclear just what the objective is. PJ thinks their sex is the ultimate sign of Ruth “giving herself” to him. But in the cold light of day, Ruth is incredulous. Their sex “meant nothing” to her; it was even “a bit revolting.” With this newfound confidence in her initial triumph over PJ, Ruth joins her family in a celebration to mark the end of the “trial.” She dances and makes out with a giantess, but then goes overboard, leading PJ to swoop in and rescue her from a group of leering men.

As the pair recover in the harsh light of day, PJ’s girlfriend Carol (Pam Grier, with frustratingly little screentime) arrives unexpectedly, exposing the unethical situation and tearing at the bond between Ruth and PJ. Ruth puts him in lipstick and a red dress to show him the neglected woman within. PJ’s psyche crumbles as he tenderly scrawls a reminder on Ruth’s forehead to “Be Kind” and stop her “cruel” torture. When Ruth refuses to play demure, both she and PJ toss and tumble over the cliff of gender one final time.

Ruth remains unrelenting, even on the final day. She considers their relationship a “defilement,” a violation of boundaries. But PJ is in love and wants to be with Ruth. The pair’s physicality leads to an outburst of violence, and when Ruth is finally able to escape, she heads out into the horizon, leaving PJ a heap of broken-down manhood in a sullen red dress. When Ruth and her family finally pick him up, she climbs into the truck bed and cradles his whimpering huddled body all the way into town.

A brief epilogue shows Ruth back in India with her mum working at an animal shelter. PJ has reformed, is still with Carol, and is now the father of twins. But an ephemeral, smoky love between the two remains.

Unlike past Campion protagonists Ada McGrath and Isabel Archer, Ruth is an explosive, rebellious, and vocal character from the very start. She seems as formidable as the landscape richly photographed by Dion Beebe, a worldly, grounded, resilient woman. Even without improvisational exercises, Kate Winslet brings a joyful self-assurance to Ruth which proves essential to the story Campion, writing with her sister Anna, aims to tell. Ruth’s grit and refusal to back down or admit she was brainwashed make PJ question everything. Once she puts him in a dress and gets on top, his psyche bottoms out.

While the dog exercise may not have helped Winslet, it’s clear that even after 30 years working as an actor, Keitel’s Method acting still helps him get into insightful psychological and experiential spaces. PJ’s passionate chase after Ruth, one boot on, red dress barely covering anything, is a boldly emotional, perhaps even highly “feminized,” performance the likes of which we rarely see from male actors of Keitel’s theater class or generation.

This being a Campion film, Holy Smoke! is filled with critiques of masculinity; just as Ruth rips off her father’s toupee in a fight, Campion exposes the insecurities lurking under masculinity and its performance. All of the men in this film are lecherous in one way or another. That Ruth, or any woman, might be able to convincingly fake pleasure (i.e., an orgasm) is a threat to PJ’s certainty and masculinity. Ruth’s bisexuality and the idea of pleasure without men send him into a rage spiral. His literal homophobic response leads Ruth to force him into gender play, stripping him of his masculine costume and agency, directing him on how to pleasure her. PJ doesn’t get to improvise this part and awakes with a post-coital clarity that destroys him. He has seen himself as a woman and must wrestle with not liking what he saw and the insecurities that flood in.

Developed as they were during the era of systems and ego psychology of the late 19th Century through the mid 20th, methods like Stanislawski’s acting technique and PJ’s psychological deprogramming assumed an essential masculinity to their “pure” subject. For them, to be without artifice was to be inherently more masculine. Control over one’s emotions was a triumph over femininity. Yet as Ruth and Campion show, contemplating the female subject—which is always defined as a non-thing or anti-subject in relation to men, causes this system to double over on itself. Removing the man’s deregulated, improvisational control and placing him into a gendered role is like asking The Method to divide by zero.

While the genderplay and critique in the film work in a myriad of ways to dispute masculinity’s chokehold on Truth, whiteness and colonial racism remain firmly intact and unchallenged. The masculinities allowed to remain reveal the coloniality structuring the narrative’s surface. The colonial masculinity lurks in the modes of domination that position foreign masculinities as strictly othering, feminine, and dangerous.

PJ’s ideas of the soul are idiosyncratic, formed by his own studies. Baba, Winslet’s guru, is a fraud who dares quote The Upanishads, Ancient Hindu mystic texts and pass them off as his own thoughts. Baba doesn’t wear traditional sacred vestments; he wears “a dress.” By not having Ruth challenge these notions, Eastern men remain fully entrenched in the classical colonial narratives of being backward, fraudulent, and feminine. Even when Ruth returns to India, she doesn’t return to Baba or her former religious community. At no point do Ruth or Campion make the connection between Baba’s monastic dress and the dress PJ will wear by the end of the movie as if both are the same kind of challenge to masculinity.

Campion refuses to connect the dots and make a thoroughgoing critique of masculinity that would overturn colonial assumptions.

From the very onset, Campion never directly connects the men in India and the men in Australia. Not only are Indian men seen as womanly con artists, but they’re also more dangerously portrayed as sexually devious. Baba’s ultimate manipulation in the eyes of PJ and Ruth’s family is a sexual one. For her, the groping men on the bus remain more threatening than Ruth’s dad wearing only a speedo and sitting uncomfortably close to Prue as she tells them Ruth has been converted.

When Ruth says she loves Baba and wants to “marry” him, she expresses it in a devotional way, not unlike how a Catholic nun is married to The Church. Yet Baba, despite only being seen once and never speaking a word, is portrayed by PJ and Ruth’s family as a post-Jonestown cult leader or a free-loving madman like Charles Manson. When Ruth becomes sick at the mandatory cult video viewing with her family, Campion and Winslet play it as though Ruth recognizes that she was more prey than an apostle.

Though PJ reveals he was once the victim of a molesting guru, Campion never bothers to connect that the one screen sexual exploitation we see is PJ using Ruth’s distressed sister-in-law Yvonne for a blowjob under the guise of helping her calm down. Carol tries to call out PJ’s abuses of power, but she’s eventually reformed off-screen.

Holy Smoke! is a movie baked in white feminism. Ruth may proudly proclaim, “my body is mine, honey!” but immediately after, when PJ says, “I’m not here to disempower you. If you want disempowerment, go back to Mother India,” Ruth can only counter that she prefers the “open sexism” of India to the liberal “repression “of The West.

This is coupled with the usual Orientalist trappings of India as “bizarre,” a cramped, wild, and unclean marketplace rich in overpowering smells experienced by Ruth’s mum. Campion’s camera reaffirms these long-standing masculinist colonial narratives of Indian religious men (indeed their men general) as leering, patriarchal, effeminate charlatans.

This lack of narrative connection weakens the film overall. Campion refuses to connect the dots and make a thoroughgoing critique of masculinity that would overturn colonial assumptions. There are such apparent parallels not being drawn that it seems to be more than mere oversight.

Campion has a blind spot when it comes to race. Watching Holy Smoke!, that becomes apparent. Yet the unchecked racism of the film also reflects the unbridled racism inherent in the methods and masculinities critiqued in the film. Holy Smoke! sees gender as the ultimate trouble with race being inconsequential. Both PJ’s methods and Method Acting at its worst cannot fathom a world overturned by gender, even producing effective work by doing so, but never one in which whiteness is supplanted. The assumed subject is always one with total freedom, which can only proceed from the colonial imagination. How can the colonized ever express freedom on their own grounds when they were shut out when deciding the terms and conditions for freedom and what freedom looks and acts like? If Keitel-as-dying-dog symbolizes a worn-down enfeebled masculinity, then the “power of the dog” that remains in Holy Smoke! is the self-styled lead and collar of whiteness.