KinoKultur is a thematic exploration of the queer, camp, weird, and radical releases Kino Lorber has to offer.

I saw my first Tom of Finland illustration in the bathroom of a Borders Books & Music. Someone had left a gay men’s magazine in a stall, no doubt along with things only detectable by blacklight. Now, I have a type and it’s not necessary for Tom’s men or domination. But I was young and gay enough at the time for any male erotica to have an effect. I left the magazine where I found it after I was through for the next curious occupant.

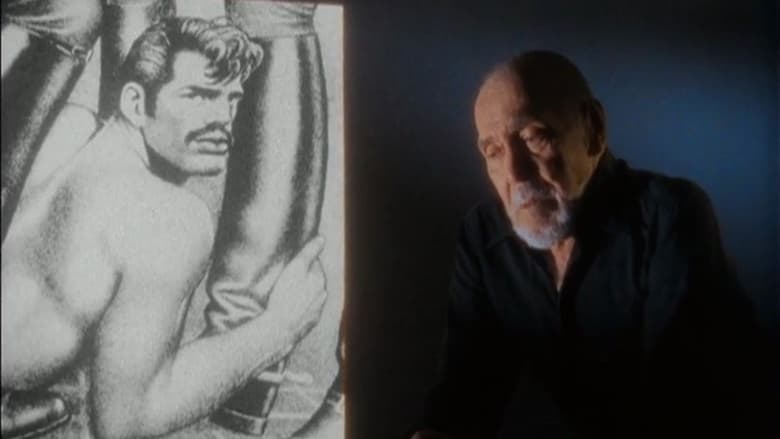

What I didn’t know at the time was that I was implicitly participating in long gay histories of magazine sharing and public bathroom play that were, in part, shaped by the images and scenes in Tom’s drawings. As explored in Finnish director IIppo Pohjola’s 1991 documentary Daddy and the Muscle Academy, available on KinoNow, Tom of Finland’s drawings celebrated a new kind of masculinity as well as a new kind of explicit yet intimate depiction of masculine bonds and bondage, which greatly reshaped the image of gay men in the public imagination.

Pohjola’s film is remarkable to watch because it in many ways typifies the New Queer Cinema movement. It’s keenly interested in 1) provocative secular-sexual imagery, 2) non-linear narrative and aesthetics, and 3) establishing evidence for and celebrating a queer culture with a history. From the very start, Daddy and the Muscle Academy is suggestive and titillating as it establishes the world of dark corners that Tom will draw inspiration from and bring into the light. As Tom will later say of his own work, voyeurism is an incredibly important mode in this film. Pohjola continually makes sure we’re only ever peeking at things and keeps our eyes scanning, only ever getting a clear steady view of Tom for his interview.

He makes us auditory voyeurs as well. Slid into several parts of the documentary are recordings of men describing and/or recreating their fantasies reflected in or inspired by Tom’s drawings. These recordings suddenly give voice to the scenes in his illustrations and we’re thrust into a documentary that is historical, animated, and pornographic. It’s often disorienting and seductive, like a hit of phantasmagoric poppers.

The film greatly benefits from having Tom alive to add his perspective. In this way, Daddy and the Muscle Academy archives the face and voices of an old guard of queer men from the 1950s and 60s who expressed themselves in print media before photography and later video took hold as the dominate means of expression and documentation. We get to hear about his time at advertising college and Tom’s idiosyncrasies as an artist, what he does to get into the fantasy mood-space in order to draw his scenes or portrait commissions.

We are also treated to an in-depth excavation of what influenced his work, which is perhaps the most illuminating part of the documentary. For better and worse. Tom loves talking about American physique or “beefcake” magazines, which were a popular male-oriented print genre starting during the 1930s and 40s, which revered and promoted the white male muscular body as an ideal form and helped popularize “men’s health,” weightlifting, and bodybuilding.

These magazines, with their sensual and adoring photos of scantily clad men, obviously had a substantial gay following, so it’s no surprise that Tom later found a home in the genre publishing (most notably in Physique Pictorial ), and would later take the beefcake genre and inject it with bST. It’s a very curious and interesting example of a cultural cycling in which a Finnish lad absorbs American gay aesthetics, adapts it, and then sells it back to Americans and helps define new American gay aesthetics.

Yet, as Tom shares, Finnish male ideals were not so different from Americans at the time. In fact, while America was gradually bulking up its American ideal, Finland was already actively cultivating an image of the ideal Finnish man as a braun, Aryan, and dominant soldier or man of authority. As Tom details in the documentary, the Finnish military had a very specific and explicit aesthetic goal in the recruits it enlisted. Their soldiers were to look tough and superhuman. And Tom found this all very hot.

So while there was a very intentional and influential back-and-forth happening with American culture, there’s a deeply European element to Tom’s illustrations that may often go undiscussed, particularly when it comes to Tom’s use of Nazi soldiers and imagery. He tells us, as a young man and soldier in occupied Finland, Tom had semi-frequent sexual encounters with German soldiers and the reality is he formed a sort of psycho-sexual attachment to the circumstances and used his art to work through them.

It’s often disorienting and seductive, like a hit of phantasmagoric poppers.

This element of personal processing requires greater unpacking when considering Tom’s “fetishism” of Nazi imagery, the (im)possibilities of consent in such situations, and what it means to sexualize (as a result of trauma) a racist militar-ideology. Especially given Tom’s barely mentioned race play drawings. But that requires delicate, nuanced, and informed discussion. So, like Pohjola, we have to not-so-gracefully sidestep away, leaving more questions than answers.

Tom knew early on that he wanted to use his talents for the male form and change this image from one of “prettiness to masculinity.” So it’s hard not to have this entanglement with Nazism gnaw at you as Tom goes on to talk about designing a “universal [male] type,” given that this was also the Nationalist project of Europe and North America at the time. They all wanted rugged men, dominate men, men chiseled by land and labor. Coupled with an uncritiqued misogyny that undergirds these ideas about masculinity, not just gay masculinity, throughout the film because it is sold and enforced as a blatant rejection of femininity because of its assumed weakness and passivity, even by Tom. Though, Tom is alo the first to admit that he, along with a lot of male pornographers, is remarkably inept at rendering feminine sensuality and pleasure.

Before Tom and the 1950s, gay men were depicted as a “third sex,” and kind of waify androgenous youth in keeping with classical models of male-male intimacies. The gay, queer, or homoerotic depictions Tom saw growing up were either from Ancient Greece which was outside his time or feminized blue bloods who were outside of his desires.

Tom’s updating of the homoerotic bond/act from the ancient past to his own near-past in the 1940s and early 50s is significant because it did allow for gay men to view themselves as present, as part of the living world. Many of Tom’s men are working class men, men of uniform, who are in total opposition to the aristocratic aesthete in pictures, which Pohjola expertly juxtaposes against Tom’s immense archive of drawings. These were men gays could go out and see in public.

And fuck in public. Pohjola rightly draws our attention to the openness of Tom’s drawings. These are not shadowy, secret scenes, shamed into corners. These are sexual encounters in the open, in public, and/or in the daytime. In this way, Tom of Finland’s drawings help reclaim and reaffirm more open and public gay sexual cultures like the bathhouse, gym shower, public bathroom, or cruising park which remain with us today.

Though it often says the quiet part out loud: that our dominant (gay?) masculine physical ideals are informed by militarism, if not outright fascism, and a firm rejection of the feminine, what Pohjola does so well with Daddy and the Muscle Academy is to show how Tom of Finland, through the circulation of his work, created and supported a community. By drawing in audio and interview recordings from gay men who have a connection to Tom of Finland, we get a clear sense of how gay men would use, send, lend, and share these magazine to see gay male erotica, which, in a profound way, made them feel seen themselves.