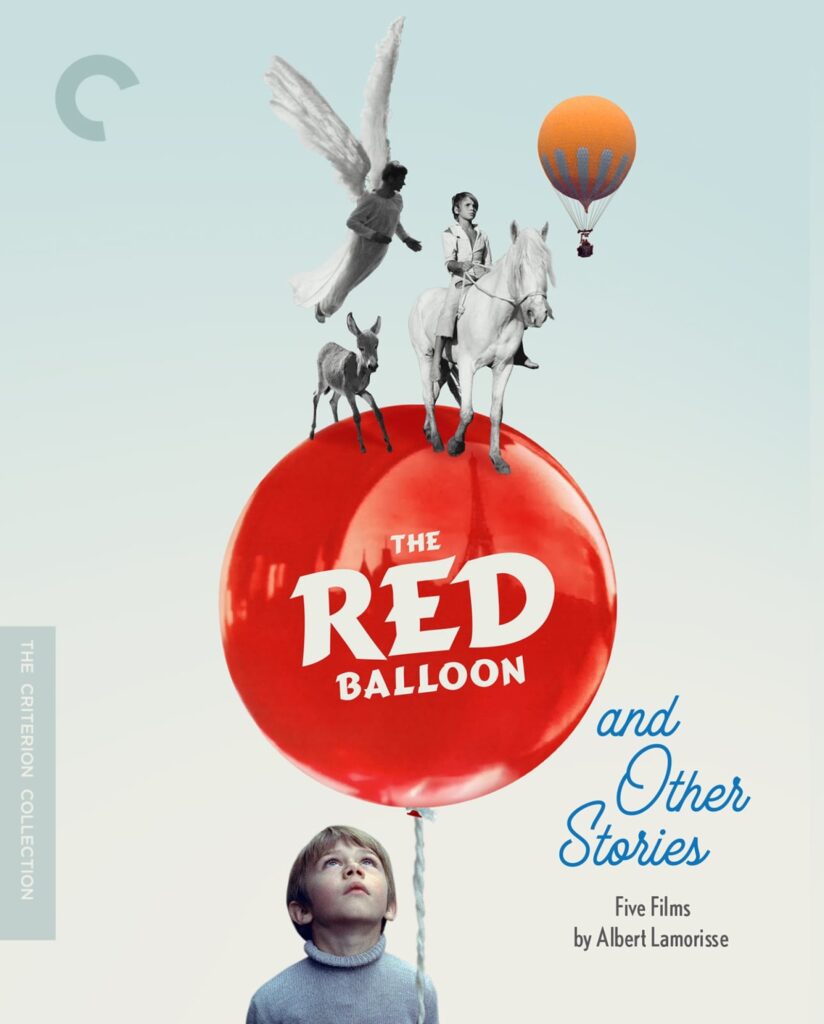

Albert Lamorisse’s flights of fancy come to Criterion courtesy of a gorgeous new box set.

There are few things more wondrous than a child’s imagination — its capacity to uplift itself beyond the pain and doldrums of everyday life to see the world through new eyes. One of cinema’s greatest chroniclers of that imagination is French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse, a contemporary of the French New Wave who literally went high where his peers went low. His domain was in short, charming, powerful films often linking child protagonists to wonders both terrestrial and supernatural: an animal that captures their heart, or the unyielding power of flight. Now, Criterion has captured that magic in a new two-disc Blu-ray set containing the bulk of Lamorisse’s flashes of cinematic whimsy.

The crown jewel of the pack, of course, is 1956’s The Red Balloon, the only short film to ever receive a major Academy Award (for Best Original Screenplay; no small feat, considering the film, like many of Lamorisse’s, relies on very little dialogue). It’s a simple, elemental tale of a boy (Lamorisse’s son, Pascal, a frequent star of his works) walking the grey, rundown streets of postwar Paris — the Ménilmontant neighborhood, to be specific — only to find himself befriending a bright red balloon that follows him everywhere. The two seem to build some ineffable connection, a bond that plays out through the streets of Ménilmontant. The boy’s parents and teachers don’t understand their friendship. His peers envy it, chasing them through the streets to tragic ends.

The effect is astonishing, even (or especially) in an age where any whim of the imagination can be achieved via CGI. Even in the gorgeous, eye-popping 4K restoration Criterion conducted for this release, one squints to see the strings, any mechanism by which Lamorisse could possibly have brought this simple red balloon to life. There’s a level of expression in this simple object, candy-apple-red against the grey backgrounds of its Paris setting, that’s nothing short of astonishing. Through the simple act of film grammar, a party favor becomes a three-dimensional character. The very definition of movie magic.

That sense of childlike wonder, combined with Lamorisse’s documentary-like realism (he got his start in doc shorts) continues through the other works highlighted on the set, albeit in different climes and with a similar sense of melancholy. His first narrative film, Bim, the White Donkey, follows another young child, Abdullah, and his friendship with an adorable donkey; the film resembles perhaps a sunnier take on Au hasard balthasar or EO, an ass as symbol for mankind’s capacity for kindness or cruelty. Abdullah must defend him first from a spoiled rich boy who also covets him; then, after said boy humbles himself and becomes friends with Abdullah, the pair must save poor Bim from some thieves. The climax, a chase across the seas with several children giving chase in a boat, is suitably thrilling. Like most of Lamorisse’s films, this adventure plays out largely wordlessly, punctuated only by narration from famed French poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert.

The White Mane, another tale of a boy and his equine, won the Grand Prix for Best Short Film at Cannes, refining the visual imagination he started in Bim. Much like the first film, White Mane champions the almost telepathic bond between its two lost souls, children breaking free of the stifling world of adulthood; they, too, flee to the sea by the end, though the narration promising a world where man and horse could be friends contrasts with the oblivion the pair swim to in its final moments. It’s a fascinating undercurrent to Lamorisse’s works, punctuating sunny poetry with harsh omens that the world is a cruel place that children, or animals, may not survive intact.

After the success of The Red Balloon came Lamorisse’s two feature-length works, the first of which feels like a movie-length extension of his preoccupation with flight: Stowaway in the Sky, a masterful 80-minute adventure charting a mad scientist (André Gille) taking his inaugural flight on a hot-air balloon of his own invention — with his grandson (Pascal, again) unknowingly in tow. The stakes are low, save for a late-film source of tension involving the balloon’s possible explosion, but that’s not the point. It’s a leisurely jaunt thousands of feet in the air, Lamorisse’s camera floating in the sky just like our protagonists; all special effects were done in-camera, making it even more impressive. What’s more, Lamorisse developed new techniques for building flying tracking shots, the CinemaScope camerawork lending each glance down at the ground an added balletic grace. If you only watch one other film of his besides Red Balloon, make it this; they’re beautiful when paired, a testament to the ecstasy of flight.

Lamorisse would meet a tragic end in 1970, when a helicopter shoot picking up shots for a new documentary in Iran resulted in a deadly crash, killing Albert while his son, Pascal, watched from the ground. But before that, he would craft one final odyssey towards the sun, fittingly featuring a man strapping on homemade wings: 1968’s Circus Angel. It’s the most narratively conventional of his films, but no less charming than the rest. This time, the protagonist is an adult, and a cad at that — a thief named Fifi (Philippe Avron) who flees the police by joining the circus. But while there, he’s cast in the role of a flying angel, fitted with wings that, after a while, actually grant him the power of flight. From there, he floats from one caper to another, finding himself in the erstwhile role of a spiritual angel for everyone from praying nuns to a couple at the altar.

The key appeal of Criterion’s set is the luxurious restorations of each of his films, though The Red Balloon is easily the triumph of the set. For those averse to foreign-language tracks, English solutions can be found on nearly all of these films; normally I’d say boo, but Lamorisse’s films are so dialogue-less and reliant on narration that the dubbing is hardly intrusive. (Plus, Stowaway in the Sky features the warm voice of Jack Lemmon, which is a lovely treat.) Special features include some 1950s interviews with Lamorisse, a modern interview with Pascal Lamorisse, and a 2008 doc called My Father Was a Red Balloon, which feels of its time but illuminates Pascal’s relationship with his father through his relationship with his daughter Lysa. An essay by David Cairns lends powerful context to Lamorisse’s seemingly effortless filmmaking, highlighting the years-long processes and meticulous trial and error that went into each of his creations.

Combined, Lamorisse’s films offer a short but powerful testament to cinema’s capacity for boundless imagination. His is a world where children can escape the cynicism of the world through magic, whether held aloft by balloons or swimming to paradise with their trusted companion. It’s a place where flight is possible, without any camera tricks or guile: just wires, years of experimentation, and the simple language of cinema. Whether you’ve got kids who could stand to sit down and watch a timeless children’s classic, or a student of the art form who wants to remember the beautiful sights it can show us, it’s an essential buy.

You can buy The Red Balloon and Other Stories at Criterion here.